Escape, Capture and Imprisonment: Charles Herridge’s 2nd World War in South-east Asia.

In 1997, at age 83, Charles Herridge decided to write a record of his life ‘before he lost his marbles’. This proved to be a prescient move as he did start to get confused soon after, the early stages of dementia, although even as the condition progressed, he kept his kindly nature and always recognised his family.

At the same time I was doing a unit in writing biography and decided I would like to focus on my father’s war experiences. He had often talked about them, generally marvelling that he had survived them. We children were too taken up with our own lives to listen but as I got older I wanted to know what happened. For my course assignment, I started with the retreat from Kuala Lumpur and ended with his capture by the Japanese off the coast of Sumatra five months later. [This account can be read HERE (<– PDF)]. Now, 20 years later, I am planning to write up the rest, his years of internment.

I interviewed Dad to fill in the gaps in what he had written and discovered that whilst some events remained very clear in his mind, he got confused sometimes about what had happened in the three different prisons – Jambi Gaol, Muntok and at Belalau. This was not surprising after 52 years, and made worse by his growing confusion.

So in this summary article, I have pieced together what I think happened and where and have written about aspects of his experiences that are not covered in other accounts, such as those of William McDougall in By Eastern Windows and Ralph Armstrong’s A Short Cruise on the Vyner Brooke.

Charles Herridge died in Canberra, Australia in 2001, aged 87.

Jenny Norvick (eldest of his five children) March 2017

Charles George Herridge was born in Fulham, west London on 6 January 1914. He was the second youngest of 6 children, 4 of whom survived to old age. Much to his mother’s dismay, Charles left school at age 15. Despite offers of desk jobs and a jewellery apprenticeship, Charles went off to work in a hardware store, first as the office boy and then as a salesman. Sales and stock management suited him and he worked in this field for the rest of his life. He did appease his mother by completing his secondary education at night school.

After eleven years working in hardware and ironmongery in London, Charles was keen to move into management but felt his opportunities for advancement in the UK were always going to be limited. He started looking for jobs in a number of British colonies.

He saw an ad in the Daily Telegraph from a company in Malaya seeking ‘selling and store experience, preferably with a knowledge of hardware’; and in September 1939 he sailed to Malaya to take up the job of running the Ironmongery Department at the John Little store in Kuala Lumpur. A few months later, the head of the food department left and Charles added food to his list of responsibilities.

In 1940 he joined the Federated Malay States Volunteer force in Selangor and became Gunner Herridge of the Light Battery. Sometime later he was approached by a man named Isaacs whom he knew socially and who was with a signals unit. ‘Isaacs told me that they were looking for a company quartermaster sergeant . Because I was running the food section at John Little, he thought I might be interested. So I went from Gunner Herridge to company QMS.’ Charles’ role was to keep the company and its signals vans well-provisioned.

THE RETREAT TO SINGAPORE

Just over a month after the Japanese landed at Khota Bharu in the north-east coast of Malaya on 8 December 1941, British fighting forces and civilians were evacuated from Kuala Lumpur. Charles packed up his big supply truck with all the supplies he could cram in and with his unit headed out of Kuala Lumpur: the Japanese were just five miles to the north, at Batu Caves. He remembered the movement south as an almost uninterrupted journey down the peninsula to Singapore, first to the town of Seremban, then to the coast at Port Dickson, through Malacca and into Johore. Just three days after their evacuation, they withdrew across the causeway into Singapore. They had not encountered the enemy face-to-face during their retreat. However Charles’ truck was subject to at least one (unsuccessful) bombing attack.

The unit set up its base in Singapore at Bukit Timah High School but moved to the former Japanese school in Middle Road just after the Japanese landed on the island. Charles’ truck was subjected to another unsuccessful bombing raid near Changi as he drove around the island trying to find supply depots to keep the signals vans provisioned.

One day he was approached by a couple of officers from the Signals Battalion who told him they had seized a junk on the waterfront near Raffles Hotel and were planning to use it to escape. They handed him the keys to a small runabout and told him to fill it with as many supplies as he could. One of the officers took him down to the junk, and told him to load the supplies onto the junk and stay there until they came. On board already was a New Zealand Lance-Corporal from Signals, whom Charles knew as Jim Lyng.

ESCAPE AND CAPTURE

They waited for the officers for 2 days through the noise and pall of battle and then an eery quiet descended. No-one came. ‘Eventually we came to the conclusion that the Japs had taken over and decided we had no alternative but to move.’

Off they set, Charles and Lyng, along with Lyng’s Thai wife and their two children. They were well-provisioned with food, water-collecting equipment and nautical maps. Lyng was an experienced sailor and Charles could speak Malay, so they hoped they had a chance of escaping. On their way through Singapore Harbour, they collected four others, all regular army, an Argyll and Southern Highlander, two men from the unit sent to turn around the Singapore guns and a young man, Ronny, whom they found rowing a sampan and (somewhat unrealistically) heading for Australia. Ronny would later pose as Lyng’s son. Their plan was to head to Java and then possibly Australia to rejoin the war there.

In the event, they got no further than Sumatra. They sailed and drifted through the Riau Archipelago and got lost for a while on inland waterways in the general vicinity of the town of Siak. Eventually they found their bearings and headed south down the coast of Sumatra stopping at villages along the way for supplies. They finally ended up staying with a fishing family and helping out on their fish trap over the sea near the mouth of the Batang Hari River.

However they had been betrayed to the Japanese who came looking for them and captured them. They were taken by motor launch up the Batang Hari River to Jambi and into the custody of a Japanese officer who smilingly asked how they had managed to escape capture for so long. It was July, five months since they had escaped from Singapore.

The group was divided up. The three regular army, minus Ronny, were sent to POW camp. Lyng’s wife and two children were sent to the Jambi women’s camp.

INTERNMENT

1. JAMBI GAOL, SUMATRA

Lyng, Ronny (posing as Lyng’s son) and Charles were interned in the local gaol.

Jambi Gaol still held local prisoners but they were kept separate from the internees who were mainly from Sumatra and mainly Dutch administrators, police, planters, priests and others, plus a few British. Charles seems to have been quartered with the Dutch as he mentioned them as his prison work mates and never mentioned Lyng or Ronnie again, except much later when Ronnie died in 1944 in Muntok, of blackwater fever.

Charles made good friends with a Dutchman named De Putter, Controlleur of the island of Singkep, located in the Lingga archipelago and they remained together until De Putter died of dysentery in Muntok.

Under the watchful eyes of local Malay guards, the able-bodied men were put to work outside the prison as ‘white coolies’. Charles and a few others were given the job of widening and deepening the silted up waterways through the town. It was an unsanitary and hazardous job clearing out rats nests and wading around in what was effectively the town’s sewer system as the residents’ outhouses sat out over the waterways.

Then they were put to work building and strengthening bridges and constructing a road. They used the spoil from the construction works to fill in the Chinese carp ponds which the Japanese thought bred malaria. Charles received a large gash whilst on bridge construction and was sent to Jambi Hospital to have the wound cleaned, dressed and bandaged. He was attended by British nurses and possibly by Dr Thompson (later interned in the women’s camp at Muntok) who had been captured and taken to Jambi.

Rations in prison started off reasonably adequate but soon were cut to meagre levels. However the internees were kept quite well fed by the local Chinese and the ‘ladies of the night’ who would find a way to leave parcels of food where the internees working outside the prison could retrieve them without alerting the guards. The workers shared the food at break time and took some back for those who were too sick or not strong enough to work.

The move from Jambi to Muntok happened suddenly. They were ordered to pack up quick smart and were crammed, 50 of them, onto a small bus designed for 30. Charles estimated that Palembang was about 250 kms away and the journey took ten and a half hours, with only one stop. At Palembang, they were rushed to the wharf, onto a ship, down into the hold and taken to Muntok.

MUNTOK, BANGKA

Charles’ friend, De Putter, was very weakened by dysentery by the time they reached Muntok and he died not long after they got there. Small things matter and he bequeathed to a grateful Charles his prized Rolls Razor which they’d both been sharing.

Not long after arriving at Muntok, Charles was approached by CG Henderson, an engineer with the railways in Kuala Lumpur whom Charles had got to know and who was working as the lay superintendent of the Muntok hospital. Henderson asked if Charles would like to work in the hospital.

At first Charles was not enamoured of the idea. He didn’t know whether he could face it but decided to give it a go. He found the first night quite distressing – there was a man in a coma who moaned all night, needed constant attention and died the next morning. However he soon got used to caring for the sick and dying and the upside was that the hospital had cleaner surroundings than the rest of the prison and was clean inside. He ended up working as a hospital attendant at Muntok and then Belalau until the end of the war.

As well as caring for the sick, he and two others put the dead in their coffins. One day two of them had to place a 6ft tall Dutch rubber planter in a coffin that wasn’t quite long enough. They decided to jack-knife him in. At the word ‘go’, they both moved to bend his body. He bent beautifully and fitted the coffin exactly.

Charles said he worked in shifts with three Dutchmen, although this may have changed over time. After De Putter died and he started working in the hospital, he formed a kongsi (group of friends who helped each other) with his own countrymen and teamed up with Alan Wrigley and George Bryant from the Admiralty in Singapore who also worked in the hospital. Charles also mentions a friendship with a ship’s purser and this would probably have been Lawrence Thompson, another hospital worker.

BELALAU, LUBUK LINGGAU, SUMATRA

And then to Belalau. Charles recounts how on the launch to Palembang he found a cache of biltong (dried meat) in a wooden box inside a small hold at the rear of the boat. He quickly lined the inside brim of his old felt hat with as much biltong as would fit and then stood guard for others to have a go. The meat lasted him for a month.

At Belalau, Charles did not go on the smuggling outings to nearby villages or on the ubi kayu raids, although he did take advantage of dropped booty to replenish supplies on two occasions. He did join a couple of alang-alang (elephant-grass) gathering expeditions to cover the hot roof of the hospital and smuggled in bananas from the nearby plantation hidden inside the grass bundles.

Food was more plentiful at Belalau but one still had to be resourceful in finding protein. Charles talked with amusement about the internee who found that grasshoppers cooked on a shovel over fire were good eating, and about the time he spotted 4 small skinned bodies on a enamel plate ready for the pot above the bed of a man nearby; they were baby rats his neighbour had found in the roof. He was grateful that the Dutchman next to him who had been born and worked as a policeman in the district knew how to catch the local frogs and snakes and how to take the poison out of the snakes and make them edible.

At Belalau bugs were ever-present. Each morning Charles would watch them crawling to the four corners of his mosquito net knowing they’d spent the night feeding on him. And he said that you knew a man was about to die when all the lice marched off his body in a long line across the floor in search of another host.

Whilst at Belalau, he nursed in the old men’s ward and looked after Fred Ritchie who was an influential man in Singapore and head of Ritchie and Bissett, Consulting Engineers and Marine Surveyors. Ritchie appreciated the care Charles gave him. He told Charles to contact him after the war and he would put him in touch with Harry Jackson who ran an importing company. ‘I think he can employ you, Charles’, Ritchie told him.

Charles often reflected on the need to have the will and focus to survive, that if you didn’t support one another or if you dreamed of being in England and having bacon and eggs for breakfast, you wouldn’t make it.

AFTER THE WAR

Back in Singapore after the Japanese surrender Charles found he was listed as ‘missing’, so his mother had not known for the whole war whether he was dead or alive. On 26 September 1945, he sailed to Liverpool on the Sobieski whose arrival was feted by the Mayor of Bootle, brass bands and a large crowd. There was much joy in Fulham when he was reunited with his mother and his brother and sisters.

Fred Ritchie made good on his promise to ask Harry Jackson whether he could employ Charles and soon Charles was off to Wales for an interview and then on the boat back to Malaya, this time to Penang as the branch manager for Jackson and Company.

In 1949 he married Patricia Nolan, daughter of Vincent Charles and Elizabeth Mary Nolan. Patricia had grown up in Penang where her father was a partner in Evatt and Co, an accounting firm. She went to boarding school in Perth, WA and she and her brother and sister were on their way back to Penang for the Christmas holidays when the Japanese landed at Kota Bharu. They were taken off the boat and sent back to Perth on a coastal steamer. Their mother, after being evacuated from Penang, sailed for Perth at the end of December 1941 and the four of them spent the war in Perth. VC Nolan stayed behind in Singapore and was interned at Changi and then Sime Road.

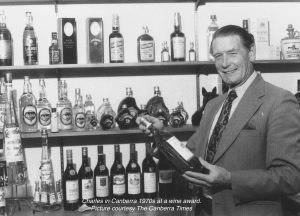

Charles and Patricia had two daughters in Penang, moved with Jacksons to Singapore in 1952 or early 1953 and in mid-1953 settled in Perth where they added three boys to the family. In 1961, after a couple of years in Wagga, NSW, the family moved to Canberra where Charles became Sales Manager and then Financial Director of a wine and spirits company.

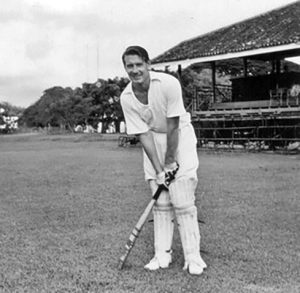

Charles played competition cricket until he was 68, was captain of the local cricket club and coached junior cricket and Aussie Rules football. When he felt he was too old for cricket, he took up bowls which he played until a couple of years before he died in 2001.