Much of the text below is based on that found on the website ‘Australia’s War 1939-1945’. We also acknowledge the Australian War Memorial from which some of the images below have been taken. We hope that this page provides further details on the events found on those two websites.

We knew we were living on a knife edge… we were starving and we were sick… if the Japs didn’t kill us, disease probably would. —— Sister Wilma Oram.

A Powerpoint presentation describing the nurses experiences during their imprisonment is being prepared for this webpage and can be viewed HERE once it has been uploaded.

On 23 October 1945, the hospital ship Manunda arrived in Fremantle.

On the wharf were hundreds of waving and cheering people including Matron-in-Chief Annie Sage of the Australian Army Nursing Sister (AANS). As the ship docked, people came on board carrying flowers and fruit. They had come to welcome home 24 Australian army nurses, women who had just spent three and a half years in Japanese captivity on the island of Sumatra and who, in February 1942, had survived the sinking of the Vyner Brooke.

The nurses were taken to recuperate in the Military Hospital at Hollywood in Perth. There they received more flowers than they had ever seen: ‘they came from every garden in Perth and kept on coming’. The matron at the hospital, Sister Eileen Joubert, had appealed over the local radio for flowers to brighten the wards for the nurses:

The response was overwhelming. The large forecourt of the military hospital was covered in blooms, some of them brought hundreds of kilometres, others carried locally in wheelbarrows.

The women’s arrival in Australia was a combination of luck and perseverance. The Australian authorities had no idea where the Japanese had taken the nurses during the last months of the war.

The search for them had started on 15 August 1945 but since no-one knew where they were, they missed out on the widespread emergency drops of food and medical supplies to the camps located around south-east Asia. By August 1945, they were starving.

Three and a half years earlier, after the sinking of the Vyner Brooke on 14 February 1942, 12 of the 65 Australian Army nurses on board were drowned or killed in the water.

The rest struggled ashore on Banka Island, some having been in the sea for more than 60 hours. One group of 22 nurses was captured and massacred on Radji Beach.

The remaining nurses were rounded up held prisoners and Japanese attempts to persuade the nurses to join a brothel were resisted by the women and they were eventually put into bungalows with Dutch women and children at the other end of the town.

The conditions were dreadful with inadequate sanitation, mosquitoes, scarce food, and unlike many of the Dutch internees, the Australians had no resources with which to purchase supplements for their diet of low-grade rice and vegetables.

In 1943 the women were moved again, this time to the atap [bamboo and palm leaf] camp that male civilian internees had built at Palembang, where they eked out an existence in leaking bamboo huts with mud floors and trench toilets.

In October 1944, the Japanese moved their prisoners back to Muntok on Banka Island. Rations were worse than at Palembang and there were few medicines. Four of the nurses died at Muntok between February and April 1944:

1. Shirley Gardam died on 4 April 1945.

2. Rene Singleton daughter of Robert George Douglas and Mary Critchley Singleton, of Maffra, Victoria, Australia. Rene ‘ … will always be remembered for her dry humour. Emaciated almost beyond recognition save for her deep blue eyes, poor Rene was always hungry – the day she died she kept asking for “more breakfast, please”. She died on 20.2.1945 at Muntok. Mrs Cross has DOD as 19.2.45. Her grave was moved to the war cemetery at Jakarta DWC-1 Plot 6 Row F Grave 6

3. Blanche Hempstead. ‘She was notorious for hard work; this assuredly hastened her end. She said she was sorry for the trouble her illness had caused, and when she death was inevitable, that she had taken so long to die’.

4. Wilhemina Rosalie Raymont. b. 1911 Prospect, South Australia. AANS Nursing Sister. Died at Muntok 8.2.45 [33]. Grave moved to Jakarta war cemetery DWC-1 Plot 5 Row F Grave 5.

Early in April 1945, the women and children were forced to take an appalling sea voyage back to Sumatra. They were packed into the holds of a small ‘bumping little launch’, many of them severely ill with malaria, dysentery and beri-beri. Others, some of them unconscious, were on stretchers and were carried by the ‘fittest’ of the women. Twenty-six hours later the women arrived at the wharf in Palembang. From there it was a train and then a truck trip to what was to be their final camp, Loebok Linggau in Sumatra.

More than five hundred women and children were squeezed into the crowded and leaking ‘atap’ huts and all their water had to be carried from the creek. At first, the food supplied was an improvement, but after a month in the camp, the variety stopped and the diet was once again rice and sweet potatoes.

We find we can eat most of the grass growing near the creek, also the young curling fronds of ferns. Curried fern with sweet potato is exactly like eating mushrooms! [Betty Jeffrey, White Coolie]

By now the women were in an appalling state but the Japanese still expected them to work in the camp. The following died at Belalau:

1. Winne May Davis of New South Wales. She was a strong swimmer and when the Vyner Brook was bombed she took to the water. Pat Gunther was in the water for many hours with her. Several times they were close to shore, only to be swept away by the strong tidal currents. Eventually, they were plucked from the water by Japanese sailors. She was described as ‘ … one of the youngest Sisters … a marvellous girl who gave herself for her friends.’ She died at Belalau 19 July 1945 [30]. Grave moved to Jakarta.

2. Pearl Beatrice Mittelheuser b.1904 Bundaberg, Queensland. AANS Nursing Sister. Died on 18th August 1945 at Belalau, three days after the Japanese surrender. Other sources give her death date as 20th August. “The only thing she wanted was to hear her people call her by her first name”. Her death certificate can be viewed here.

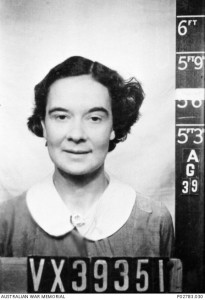

3. Rubina Dorothy Freeman AANS Nursing Sister – 10th Australian General Hospital. Died in captivity at Belalau, Loebok Linggau on 8.8.1945 [32]. Her grave was moved to Djakarta after the war.

Mittelhauser |

Freeman |

After the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, Australian war correspondent Hayden Lennard began searching for the nurses. By following a number of leads from local villagers he eventually located them in their camp at Loebok Linggau.

On 15 September, one month after the Japanese surrender the nurses were told they would be flown out of the camp.

At 6.00 am the next morning, sixty women from the camp, including the Australian sisters, were driven in open trucks to the railway station. It took them nearly 3 hours to travel the 12 miles. At the station they were met by Hayden Lennard and a RAAF pilot, Flying Officer Brown, who had been landed at the Lahat aerodrome to collect them.

The two men accompanied the women on the train to Lahat where they waited for their aircraft to arrive from Singapore. Nearly four hours later they watched it land. Out stepped the Matron-in-Chief of the AANS, Colonel Annie Sage with Major Harry Windsor and Sister Jean Floyd, one of their colleagues from the 2/10th AGH, who had managed to escape safely from Singapore. Expecting to recover many more of the nurses, Colonel Sage looked around at the small, emaciated group and asked: ‘But where are the rest of you?’

The Australian Army doctor who travelled with the rescue team, Harry Windsor, was so outraged by the appearance of the surviving nurses and the other prisoners at the camp that he recommended, officially, that the guards, the Kempei Tai [military police] and all of those Japanese involved in their treatment, be forthwith slowly and painfully butchered.

[Report of Dr Harry M Windsor, Major, 2/14th AGH, 19 September 1945. NAA MP742/1 Item 336/1/1289]

Historian Michael McKernan, who discovered Dr Windsor’s report in the Australian Archives in Melbourne, wrote of his reaction to the doctor’s words:

The savagery of this statement would leap at any researcher however drowsy in the hushed quiet of an archival reading room. The words were more dramatic for me as I had known Harry Windsor in his later life; his son is one of my closest friends. The passion, the grinding anger, is entirely at odds with everything I knew of this man or had been told of him. Those few words of brutal and savage retribution, ‘slowly and painfully butchered’, I have no doubt were precisely what Harry Windsor wanted to order for these Japanese whom he now despised for what they had done. [Michael McKernan, This war never ends, UQP, St Lucia, 2001, p 73}

The nurses’ aircraft landed in Singapore at dusk that evening and they were taken straight to the Australian hospital at St Patrick’s College. There they learnt to sleep on proper beds with sheets, to enjoy proper food and for the next few weeks they were ‘fattened up’.

On 4 October 1945, after enduring three years and seven months as prisoners of war, the 24 sisters sailed for Fremantle, Australia.

Simons, J.E., In Japanese hands. Australian nurses als POWs (Melbourne 1985)

Kenny, C., Captives. Australian army nurses in Japanese prison camps (St. Lucia 1986).

An Article in The Sydney Morning Herald describing the experience of one of the nurses – Nesta Janes – can be read HERE.

NFX70498 Captain Winnie May Davis, 10th Australian General Hospital, Australian Army Nursing Service DOD 19 July 1945. Story delivered 14 February 2015

Today we remember and pay tribute to Captain Winnie May Davis.

Winnie Davis was the eldest daughter of James and Laura Davis, born on 7 July 1915 in Ulmarra, in the Clarence River area of New South Wales. Prior to the breakout of war she worked as a nurse, and was known as “Win”. At 25 she enlisted into the Emergency Unit on 10 December 1940 at Victoria Barracks, Sydney.

Davis disembarked at Singapore in March 1941 and was attached to the 10th Australian General Hospital of the Australian Army Nursing Service. From there she was sent with the unit to Malacca. In those early months conditions for the nurses were good. They attended dances, were able to utilise sports clubs’ facilities, and could travel to Kuala Lumpur or Singapore when on leave.

This changed when the Japanese began to invade the peninsula. The 10th AGH’s position became unsustainable, and its staff soon retreated to Singapore. Here conditions were difficult, with frequent blackouts and casualties coming in at a fast rate.

The Japanese landed on the island on the night of 8 February, and with the fall of Singapore imminent the decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Davis was among the last of the nurses to be evacuated, and left on 12 February – three days before Singapore’s capitulation.

Davis boarded the Vyner Brooke along with 300 others, mostly women and children. It was a slow vessel, and two days later in Banka Strait it came under attack from Japanese aircraft, and the order was given to abandon ship.

In the water Davis and fellow nurse Sister Janet Gunther clung to a bit of wood until they found a raft. The raft already held another nurse, a radio operator and two British sailors, one of whom was badly burned, and later three civilian women joined them. It was a small raft, so those who could took turns to swim beside it while holding onto the ropes. One of the civilian women fell unconscious and drifted away, never to be seen again. The wounded sailor also slipped off the raft during the night, and the others were too weak to pull him back.

Suffering from abrasions, exhaustion, and severe sunburn, the group was picked up by a Japanese ship. The prisoners were given a drink and a little food and were kept in a pig pen overnight. The next day they were taken to a gaol in Muntok, and then on to Palembang.

As prisoners of war they suffered many privations – poor sanitary conditions, limited food and water supply, cramped sleeping areas – and conditions only worsened as the years went on. The group moved camps numerous times, usually for the worse, and all were put to hard labour. In 1945 an epidemic of “Banka fever” swept the camp; the symptoms were high temperature, periods of unconsciousness, and skin infection. On 19 July Winnie Davis died of illness, less than a month before the end of the war. She was 30 years old.

Davis is buried at the Jakarta War Cemetery in Indonesia, and her name is listed on the Roll of Honour on my left, along with some 40,000 Australians who died in the Second World War. Her photograph is displayed today beside the Pool of Reflection.

This is but one of the many stories of service and sacrifice told here at the Australian War Memorial. We now remember Captain Winnie May Davis, and all of those Australians who gave their lives in the service of our nation.

Jennifer Surtees: Last Post Ceremony Project Team

Sources: National Archives of Australia, Winnie May Davis, service record.

Below, the image is an embroidery completed in Palembang, Sumatra of a large eucalyptus gum tree and surrounding landscape. A number of Australian nurses, including Pat Gunther, survived the sinking of the ‘Vyner Brooke’ and endured captivity at Palembang and Muntok. The women developed ways of surviving the harsh conditions, and ways of maintaining tenuous links with normality, however remote normality may have been. A silver jam spoon and pair of eyebrow tweezers came to signify the last vestiges of a civilised world. This embroidery was woven from threads pulled from clothing at the prisoner of war camp.

A PREQUEL

Before the stories told above unfolded, the journey taken by the AANSs began on 4th February 1941 with the sailing of the Queen Mary from Sydney with the destination being Singapore. On board were elements of the 8th Division AIF and 51 Australian nurses. Forty-three nurses were from the 2/10th Australian General Hospital and 8 nurses from the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour was still some 10 months away and the Fall of Singapore a year away. The Queen Mary arrived at Fremantle, WA on 9th February and sailed for Singapore on 12th, arriving on 18th February.