The following description of the Muntok Memorial Peace Museum was written by Judy Balcombe who led the effort to raise the funds necessary to build the museum and it is thanks to Judy that the museum was created.

Some years after it was built, the building began to suffer some damage and more funds were need to make the necessary repairs which were completed in 2024. A photographic record of the renovated museum was made soon afterwards and this can be viewed HERE (pdf).

A Memorial Plaque was placed by the jail where the male internees were held and reads:

In loving memory of civilian men, women and children and Allied servicemen and women held captive at Muntok on Banka Island, and in Palembang and Loeboek Linggau camps on Sumatra, from 1942 to 1945.

Many evacuees from Singapore were bombed and drowned in the Banka Strait, others including 21 Australian Army Nurses were massacred after landing at Radji Beach.

The surviving evacuees suffered deprivation, disease, or death in their 3 and a half years of captivity.

Another plaque has been placed in old Changi Museum, in the presence of internees’ families and former internee Neal Hobbs, then aged 89, who helped to bury his friends and fellow prisoners who had died in the Muntok Jail, Banka Island.

Muntok Peace Museum, opened September 2015

Muntok is a small town at the Western tip of Bangka Island, Indonesia, lying off the coast of Sumatra, which is visible in the distance. In 1942, during WW2, the Japanese wished to capture Bangka Island as a fuelling station for planes flying to fight for the rich oil fields of Palembang in Sumatra. Bangka Island was bombed in early February and Japanese troops landed in great numbers in mid-February.

The Japanese Imperial Army had already invaded Malaya on December 8, 1941 and had fought their way down the Malay peninsula. Towns were bombed and captured and there was great loss of life. The Japanese dropped leaflets reading “Burn the white devils in the sacred flame of victory !” As the Fall of Singapore became imminent, European civilians were suddenly urged to leave the island by any means possible. Women, children and elderly men, civil servants and servicemen en route to fight in Java rushed to the Singapore docks to board a flotilla of large and small vessels to try to sail to freedom.

The Muntok Peace Museum website tells the story of these evacuees. About 5,000 lost their lives in the bombing of over 100 vessels in the South China Sea and in the Bangka Strait off Bangka Island.

Many 100’s suffered and died in the harsh Japanese camps of Muntok on Bangka Island, Palembang, and Belalau camp at Lubuk Linggau in Sumatra.

Other prisoners were held in separate camps at Bankinang, Padang, Sumatra and will be the focus of another project.

The Muntok Peace Museum was established as a memorial to these people – those lost at sea, many of whose names are not known, and to the people who died in these prison camps, particularly in Muntok.

Unfortunately, most of the British, Australian, and New Zealand graves at Muntok were abandoned after the War, despite requests to authorities to preserve them or place a memorial.

The British, Australian, New Zealand, and Eurasian evacuees from the bombed boats were joined in prison camp by a similar number of Dutch civilians who had been living and working in Indonesia and who were brought into prison camp from their homes.

The Dutch lived together with the shipwrecked victims and shared 3 and a half years of hardship, sickness and starvation. After the War, the Netherlands War Graves Foundation looked after all Dutch military and civilian graves, moving them to larger War Cemeteries in Java.

The majority of British, Australian and New Zealand civilian graves, however, were not moved as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission does not have responsibility for Civilian graves. The remains of these civilians now lie in Muntok under houses, a petrol station and in a group grave.

The people of Muntok are very proud of their long history. The government Timah Tinwinning Museum has excellent displays dating back many centuries, showing Indonesian culture and the history of tin mining on the island.

The Timah Museum also has the Vivian Bullwinkel Galleri, which tells of the events of February 1942, when Muntok was bombed by Japanese planes and invaded by soldiers from warships. Houses were burnt down, people were killed and women were assaulted. The people of Muntok town were terrified and many left their homes to live in the large cave at Batu Balai until ordered back to work by their captors. The local population lived in fear and hunger throughout the War.

Australian Army Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel was the sole nurse survivor of the Radji Beach massacre, near Muntok on February 16, 1942. 21 Australian Army Nurses from the bombed SS Vyner Brooke, civilians and up to 60 British and New Zealand servicemen were killed by Japanese soldiers at Telok Mengeris (Telok Inggris or English beach), now known as Radji Beach.

These Nurses had been evacuated from their work caring for the wounded in Malaya and Singapore, under Army orders against their wishes, for their protection, following the rapes and murders by Japanese soldiers from the Orita Battalion at St. Stephen’s College Hospital, Hong Kong on December 25. Unfortunately, on reaching Radji Beach after the Vyner Brooke was bombed and sunk, 22 Australian Army Nurses, civilians and servicemen encountered the same Orita Battalion which had rampaged through Hong Kong and Nanking.

The Vivian Bullwinkel Galleri in the Timah Museum has displays about the Australian Army Nurses – the 12 who died in the bombing of the SS Vyner Brooke, the 21 Radji Beach victims, and Sister Vivian Bullwinkel and her 31 Australian Army Nurse colleagues who entered the harsh prison camps which followed.

The Timah Museum also has displays concerning Mr Vivian Gordon Bowden, Australia’s Official Representative to Singapore, who had been captured in Muntok and murdered by 2 guards on February 17, 1942.

After the Vivian Bullwinkel Galleri opened in 2013, we were contacted by a member of the Muntok Heritage Community suggesting there was scope for a separate Museum showing the long and difficult years endured by prisoners in the harsh Japanese Prison Camps. Here one half of men and one third of women prisoners had died from sickness – malaria, dysentery, beri-beri and starvation.

Friends and families of the internees committed enthusiastically to this project, and gathered donations to build the small Muntok Peace Museum, which now stands in the area of the former Women’s Prison Camp. The fundraising was a labour of love and people helped in many ways. Individuals sent sums they could afford, sold personal items and held garage sales to raise money. I complied and sold a cookbook with recipes the prisoners had written down in camp to ease their hunger while they longed for better days. The Malayan Volunteers Group and the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia helped with generous donations, BACSA writing that “ the Muntok Lost Graves represented one of the saddest stories they had known”.

An afternoon tea was held at the Australian Nurses’ Memorial Centre in Melbourne, established by Vivian Bullwinkel and her fellow prisoner Sister Betty Jeffrey after the War. Vivian and Betty had dreamed of such a Memorial during their years in Prison Camp. On returning home, they had travelled around Victoria in a small car, speaking publicly at hospitals and to community groups to raise funds. A Melbourne radio station had run a campaign for donations towards the Nurses’ Memorial Centre, the largest ever held. A building was purchased in Melbourne in 1950 to provide education, accommodation and companionship for all Nurses, in memory of Nurses who had served in War.

This successful outcome was our inspiration to see the Peace Museum come to fruition. It would tell the story of War years and be a tribute to the many who had died in in the sea and in Muntok Camp, particularly the graves not moved to Commonwealth War Grave Cemeteries or otherwise remembered.

The land for the Muntok Peace Museum was donated by Kampong Menjelang, the site of the former Women’s Camp. We asked that the building could also be used as a meeting room for women and a place for children to do their homework. Finally, the first sod was turned in the ground next to the Kampong Menjelang primary school and mosque.

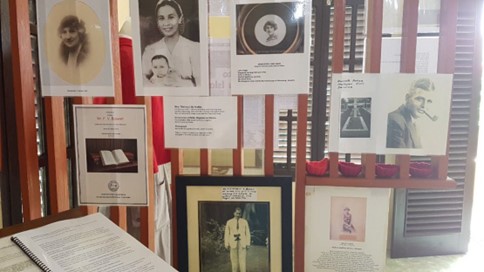

Each week photos of the building progress arrived by email and within a few months, the work was completed. The Museum comprises a large open room on pillars, in the traditional Indonesian style. Inside, vertical slatted wall dividers and glass cabinets allow for many displays. New items for the Museum are always welcome.

I would now like to take you on a virtual tour of the Muntok Peace Museum. Bangka Island today is a warm and welcoming place and visitors will be shown great kindness and hospitality. But I am aware that many people will not be able to make the physical journey and so would like to show you the many displays, to explain the history and to tell of the courage and resilience of the brave people this Museum members.

Please come with me past the smiling schoolchildren and up the steps into the Muntok Peace Museum. It is a simple building, to represent the hardships experienced by the prisoners. Unlike the dirt floors of the prisoners’ huts, here the floor is made of cool green tiles. There are also air conditioning units to preserve the items and for your comfort.

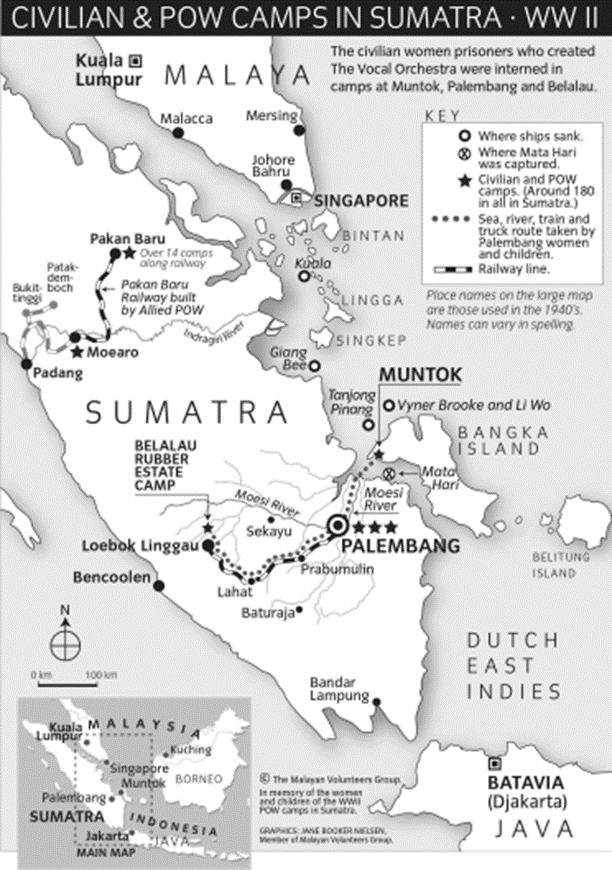

A large map from 1943 on the rear wall of the Muntok Peace Museum has pins marking Muntok, Bangka Island where shipwrecked victims

landed in February 1942, Palembang in Sumatra where civilian and military prisoners were sent from Muntok and remained for long periods before being returned to Muntok. From here, the prisoners were moved yet again to the final camp at Belalau in the remote mountains of Sumatra. Each move brought reduced food rations and increased sickness and death. The prisoners at Belalau felt this isolated area had been chosen so they could never be found.

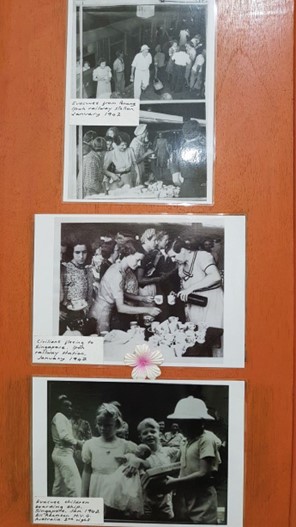

Near the entry of the Muntok Peace Museum, we see a photos of women and children evacuees who travelled down the Malay peninsula in February 1942, hoping to board ships leaving for safety.

Next we see a page listing some of the estimated to be over 100 boats carrying these evacuees which were bombed and sunk.

“Horror off Bangka” is a sketch showing victims from a bombed ship clinging to a piece of wood, drawn in prison camp by New Zealand Navy Lieutenant William Bourke, and hung here with his son’s permission.

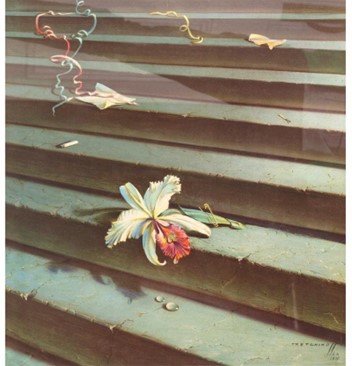

Postcards of paintings by Russian artist Vladimir Tretchikoff are displayed on the wall. Tretchikoff was evacuated from Singapore on the SS Giang Bee, one of the larger boats sunk, with only 70 people reaching Bangka Island. He had volunteered to shovel coal in the engine room, which he described as entering into the depths of Hell. Tretchikoff’s lifeboat from the bombed Giang Bee reached Java, where he was briefly imprisoned but then freed, as Japan was not then at war with Russia. We see his paintings of The Lost Orchid – a delicate flower with a pin, lost from a dress, discarded on a flight of steps with streamers and a cigarette – surely reminiscent of party-goers fleeing a dance hall to rush to the Singapore docks. Another picture shows a single pink rose in a glass, standing in a rough open window, overlooking a peaceful tropical scene, which the evacuees had hoped to reach; the third painting is of a pink rose which has fallen and lies hanging from a glass.

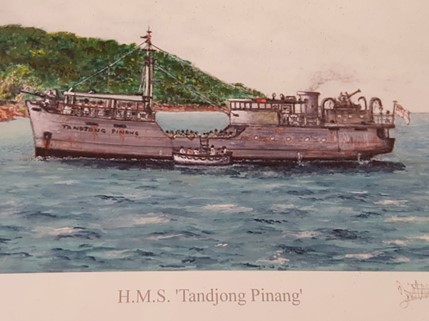

There is a painting of the Tanjong Pinang which rescued many people from the Kuala and other bombed boats near Pom Pong Island, only to be itself shelled and sunk, with further great loss of life. This was painted by David Wingate in memory of his grandmother Penelope Landon, who died in the bombing of the Tanjong Pinang, aged 50. Penelope’s photo hangs on the photo wall. British Nurse Margot Turner, later Brigadier Dame Margot Turner, was one of the few people from this double catastrophe to reach Bangka Island, the only survivor on her raft. She had recalled how, one by one, the victims with her, including children, became dehydrated and died and how she had rolled their bodies into the sea.

A mannequin wears Australian Army Nurse’s uniform from the period, with regulation grey dress and red cape. After the Vyner Brooke was bombed, the Australian Army Nurses’ tore their clothes to use as bandages and or to use as sails on a raft. 32 Australian Army Nurses entered the prison camps but 4 later died in Muntok Camp and 4 at Belalau, leaving only 24 who finally returned home.

Next is a photograph of Stoker Ernest Lloyd and his wife, one of the 2 male survivors of the Radji Beach massacre. He, like American Eric Germann, had been wounded in the massacre but escaped death and survived the War. Like Eric Germann and Vivian Bullwinkel, he was able to report this terrible tragedy.

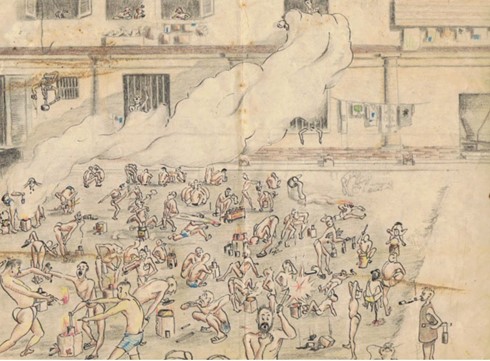

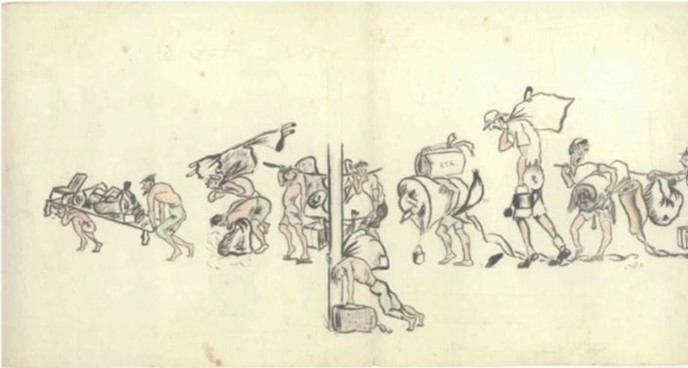

Copies of further drawings by Lieutenant William Bourke show the hardships of prison camp life. In these detailed paintings, we see men running to catch rats to cook for dinner and small groups squatting in a crowded compound over smoking cooking fires. Another of his pictures, stretching over two pages, shows a line of gaunt, ragged men carrying their worldly possessions in small bundles, staggering as they are moved to yet another, and worse, prison camp.

A line drawing of the layout of the Muntok Jail and coolie lines was drawn from memory by former child internee Theo Rottier. The Jail was built to house 250 people but during the War, nearly 1000 men were crammed inside, with boys over 10 who were taken from their mothers.

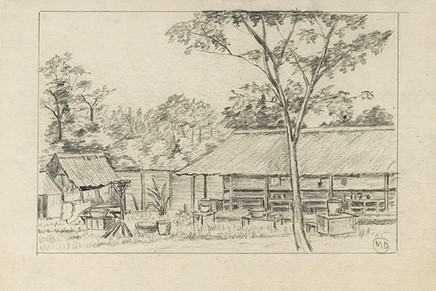

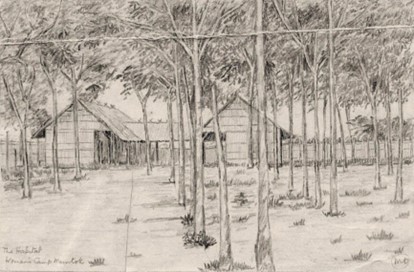

Internee Margaret Dryburgh made many fine drawings in the Camps. She gave some as gifts to fellow prisoners, for birthdays or simply ‘to lift them when they were down’. She drew detailed pictures of the primitive huts and the attempts at a vegetable garden in Palembang Barracks Camp, never harvested, as the prisoners were moved on before the garden flourished. We also see the rough communal kitchen at Palembang, where huge rice pots burnt the cooks as the boiling rice splashed, a ‘bedroom’ and the rudimentary Muntok ‘hospital’ hut, which had no medicines or facilities. The drawings are an invaluable record of the hardships of Prison Camp life.

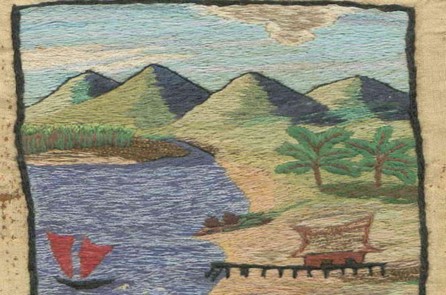

Margaret Dryburgh was a missionary who also wrote the Captives’ Hymn, which was sung in camp each Sunday and beautiful poems. ‘The Burial Place’ hangs on the wall with a painting of a quiet tropical scene. This poem tells of the beauty of the clearing where the women dug graves by hand to bury their friends – a peaceful, sacred place, with sunlight and flowers.

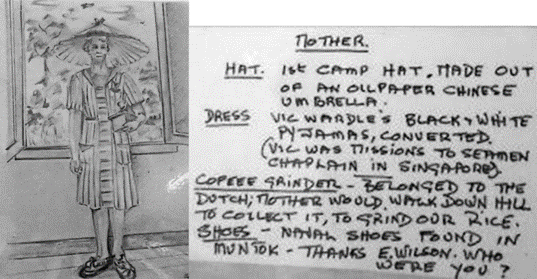

Families have sent items and photos of their relatives with brief biographies. There is a sketch of Mrs Mary Brown, wife of E.A. Brown, choirmaster of Singapore’s St Andrew’s Cathedral, wearing the dress she made from Reverend Vic Wardle’s striped pyjamas and a sun hat she created from a broken umbrella. She is wearing a large pair of men’s shoes left behind in the Muntok jail in February 1942 by a sailor. Many people had cast off their shoes in the water following the bombing of their ships and thereafter, went barefoot.

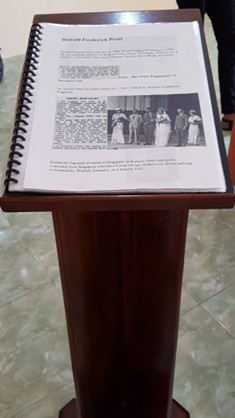

Anthony Pratt gave copies of letters written to his Mother by friends who had known his Father in the prison camps. Poignantly, they describe Donald Pratt’s humour and good nature, particularly in relation to the Camp concerts held in Palembang. These letters also tell of Donald Pratt’s physical decline after he was forced to labour in the Palembang oilfields and his early death, aged 34.

The Camp diary of Gordon Reis has been copied and enlarged in 3 volumes and given to the Muntok Peace Museum by Reis’ grandson, David Man. This diary tells of Gordon Reis’ ‘Slow Death by Starvation’ and is a detailed account of his deterioration. Reis carefully describes his symptoms and records his decreasing weight, until he can write no more.

A photo of Kenneth Dohoo has been sent by his family for the photo wall. In the words of internee William McDougall, who wrote 2 books about the camps after the War, Kenneth Dohoo was ‘uncomplaining, cheerful, tolerant and cultured, a genuine gentleman, heart and soul’, who tragically died from malnutrition and malaria aged 38.

Next we see a photo of Dr Albert Stanley McKern, an Australian doctor and obstetrician, who worked in Penang, delivering many babies safely. As he was dying from amoebic dysentery in the final camp at Belalau in Sumatra, Dr McKern asked for a pencil and paper to make his will. He asked that when his family were grown and independent, all his assets would be sold and the proceeds given to obstetric research. In due course, this occurred and the sum of $12,000,000 was then shared between his universities of Sydney, Yale and Edinburgh, to help improve pregnancy and childbirth care. He is fondly remembered to this day in Penang, where some people have seen his ghost walking on the beach at night.

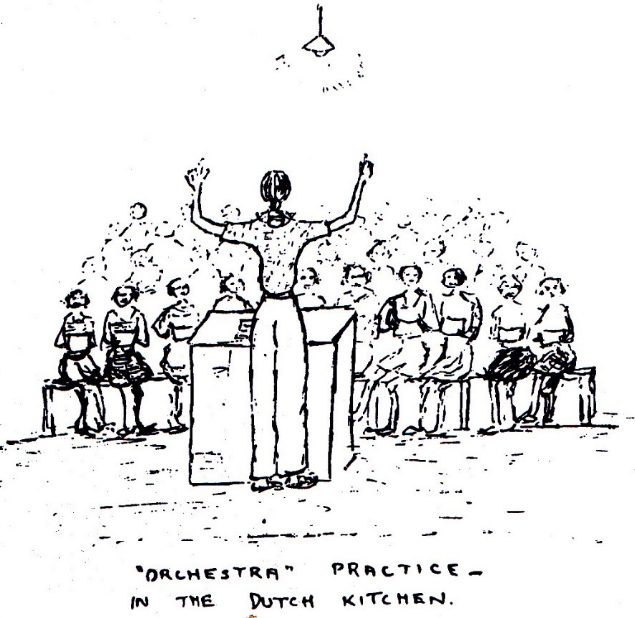

Among the drawings of rough huts, cramped conditions and women emptying latrine buckets, is a display of music with an explanation in English and Bahasa Indonesia. In Palembang prison camp, while living in bamboo huts, the women prisoners formed a vocal orchestra. They were taught by internees Margaret Dryburgh and Norah Chambers, both classically trained musicians. There were of course, no instruments for an orchestra, so the women learnt to hum the notes. A vocal orchestra meant that women of different nationalities and languages could sing together without words. Gatherings were prohibited, so the women practiced in small groups before several concerts were held outside at night. At first the Japanese guards were furious but then they too listened quietly to the wonderful music. The singers and audience said these concerts helped them to endure the horror and degradation of the camps.

In 2013, a concert was held in Chichester, UK, with music from the original vocal orchestra scores. Ticket sales helped the school now on the site of the Women’s camp and to build a memorial grave for those who died in Muntok and still remain here without individual graves.

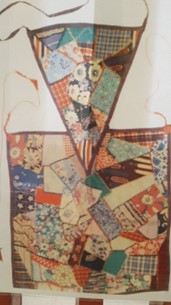

On a wall divider, we see pictures of items made by the Women prisoners – an embroidery made from threads pulled from clothes, an apron put together from scraps cut from the Women’s dresses as a gift for Margaret Dryburgh, a mahjong set carved from scraps of wood, an embroidered nursery rhyme book made for 2-year-old Robbie Patterson at Christmas 1942, and a rag doll made by Mrs Mary Brown for her unborn grandchild. Mrs Brown died in Camp and so never met the baby, but the doll was taken home to Ireland after the War and was treasured. Her grand-daughter and the doll both came to the Chichester concert in 2013.

There is also a photo of Bully, a small Japanese soldier doll in uniform, made by Australian Army Nurse Betty Jeffrey and given to Vivian Bullwinkel. The original doll is now in the Australian War Memorial in the nation’s capital in Canberra.

Small sketches drawn by Betty Jeffrey were copied with her family’s permission and are also on display. The punishment for having written material in Camp was dreadful – solitary confinement on reduced rations or worse, so Betty’s drawings are tiny by necessity. But individual people can be made out in the stick figures bowing in a line at a Tenko roll call and rehearsing the vocal orchestra music in the Dutch Camp kitchen.

Glass cases hold copies of books written by the prisoners after the War – Betty Jeffrey’s White Coolies, Pat Darling’s Portrait of a Nurse, child internee Ralph Armstrong’s A Short Cruse on the Vyner Brooke and child internee Des Woodford’s memories. Nurses’ white collars and badges are on display.

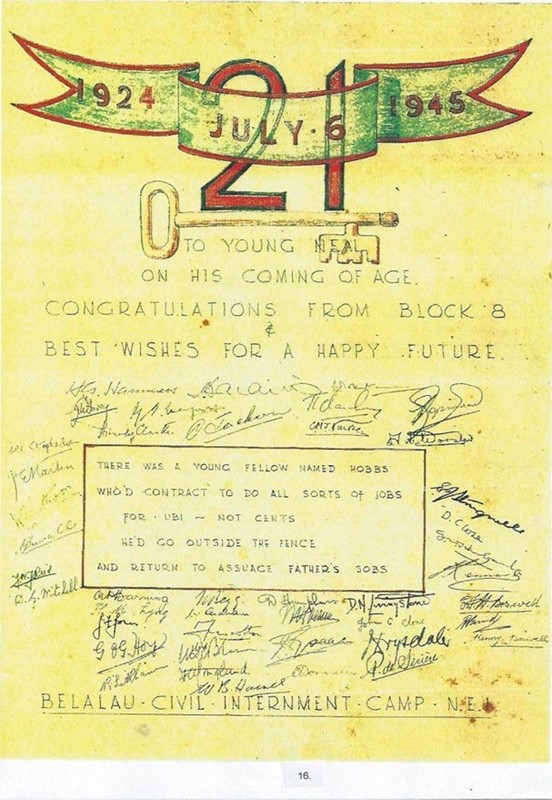

Neal Hobbs’ 21st birthday card made in Belalau Camp and wishing him a long and happy life was signed by all the men in his hut, including the staff of murdered Australian diplomat Mr Vivian Bowden. The poem on the card refers to a dreadful occasion where Neal was spotted by Japanese guards returning to Belalau camp after a night outside the barbed wire, foraging for tapioca roots for food. Others had been executed for leaving camp. On this occasion, Neal’s small stature, inherited from his jockey father, probably lead his captors to think he was a child. He was locked up and beaten all day but then returned to camp life.

A shelf holds a solar topee, the tropical white hat once worn by Europeans, a Japanese army helmet and the split-toe rubber shoes worn by Japanese soldiers. A wooden carved head of an old and very thin man represents the hunger experienced by the prisoners. Food rations were very low – a small half coconut shell demonstrates the meagre amount of rice provided to the prisoners for meals. There was almost no meat, fish or eggs for protein, no fat but a small amount of green vegetable, often kangkong, a type of water weed. Prisoners resorted to eating rats, snails, and snake – anything they could find.

Inadequate nutrition, dirty and poor water supplies, overcrowding and lack of medical care caused patients to develop beri-beri and pellagra deficiency diseases, affecting breathing, eyesight and the ability to walk. These, together with infectious diarrhoea of dysentery, Malaria and Bangka Island fever, tuberculosis and the effects of starvation and general debility led to serious sickness and death of hundreds of prisoners. The Nurses and internees tried to care for one another, but with no medicines, there was little help for these otherwise preventable and treatable conditions. But the dying received care and kindness from the friends who nursed them and no one ever died alone.

The men carried the bodies of their friends a mile to the local town cemetery, where they said prayers and placed leaves on the coffins. The women buried their friends under trees at the edge of the camp – after the War, Dutch authorities moved the women’s bodies into the town cemetery. As explained, in the early 1960’s all Dutch military and civilian graves were moved to large War cemeteries in Java. The British authorities arranged for the Dutch to move British and Australian military graves but the British and Australian and New Zealand civilian graves were largely left behind in Muntok. A small number of these civilian graves appear to have been moved in error as the people’s titles as Volunteers suggested to the Dutch that they were military personnel. Some of these graves were moved by employers but the majority of Muntok British, Australian and New Zealand graves were left behind, where they were built over by houses and a petrol station in the late 1960’s, becoming known as Muntok’s Lost Graves. A visiting religious minister had taken photos of the abandoned graves in 1968 and we see his photos here.

During the building of the petrol station in 1981, 25 bodies were found and reburied in Muntok’s Catholic cemetery. It is believed from the old cemetery plan that these were some of the women from the women’s camp.

In 2015, 2 plaques were placed on this memorial grave in the Catholic cemetery, with the names of all the people who died in Muntok and who we believe still remain buried there and bearing words from Yeats’ poem, “Tread softly, for you tread on my dreams.” A replica of the plaques with names stands near the entrance to the Peace Museum.

At the end of the War, the Japanese concealed the existence of Belalau camp in Sumatra and denied there were any more prisoners to be found and liberated. In February 1942, while a prisoner in the Muntok coolie lines, Vivian Bullwinkel had told Australian Army Major William Tebbutt about the massacre. He was later moved to Japanese military prisons but knew that 32 of the Nurses had entered prison camp and had tried to follow reports of their whereabouts throughout the War. After the War ended on August 15, 1932, Major Tebbutt continued to request the Australian government to look for surviving Nurses. It was through his persistence that Belalau Camps, with the 24 surviving Australian Nurses, British Army Nurses and men, women and children internees were finally found a month later.

South African Major Gideon Jacobs and his small troop of soldiers had parachuted into Sumatra to take charge of the camps and to make sure the Japanese did not kill all the prisoners, as it was believed would happen. The prisoners still alive at Belalau were sick and skeletal – the liberating team and Australian journalists who came to Belalau wrote that the prisoners looked like those from Nazi concentration camps.

Front pages of newspapers from the end of the War, with headlines – ‘Peace – World Hails Jap Surrender’, ‘Japanese Accepts, Says Tokyo’ and an end-of-war souvenir handkerchief are on a wall-divider, under a carving of flying geese, to represent freedom and a metal Peace dove.

Since 2017, an annual memorial service to the war victims has been held in Muntok, or, during Covid, participants joined remotely on Zoom.

Family members of the Australian Army Nurses and civilian internees are joined by the Embassies of Australia, New Zealand and Britain and Indonesian authorities, the Muntok Red Cross and many friends. The Director of the Netherlands War Graves Foundation has also attended this memorial service. Services are held at the Peace Museum, the Nurses’ memorial at the Tanjong Kelian lighthouse and at the headland overlooking Sumatra. Prayers and poems are read, wreaths laid and flowers thrown into the water.

In 2017, a group of current serving Australian Army Nurses held hands and walked into the sea, as Vivian Bullwinkel reported she and her colleagues did on February 16, 1942, before they were shot. This walk has become known as The Walk for Humanity and each year now, following the services, all present hold hands and walk into the water, hoping and praying for Peace in the world.

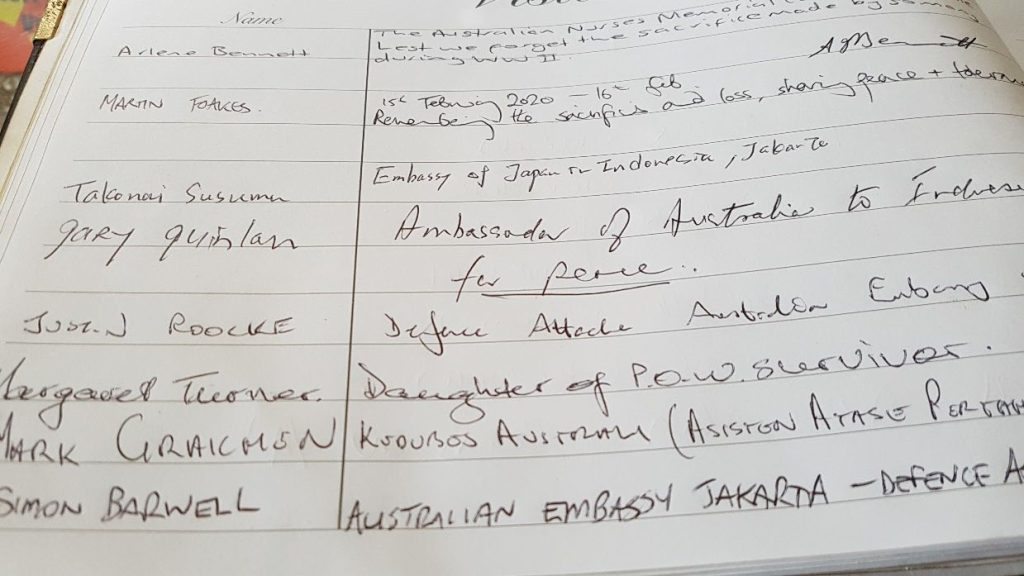

In 2020, Mr Takonai Susumu, the Political Advisor to the Japanese Embassy in Indonesia visited Muntok to attend the memorial service. He joined in the Walk for Humanity and the 4 Embassies planted a Tree for Peace, a rosebush, in the garden of the Sudirman homestay, the former residence and office of prison camp commandant Captain Seiki Kazue. A plaque now stands in this location, which has become a beautiful Peace Garden. The Embassies also signed the visitors book in the Muntok Peace Museum, leaving messages of Peace.

1,000 folded paper cranes have been placed on the wall of the Museum, symbolising the wish for World Peace. There is also a green Japanese obi (sash) embroidered with gold flying cranes of Peace and Freedom. We and the local people would like visitors to know that War is very harmful and to try to prevent it from happening again.

Small yellow roses are tucked into the exhibits, replicas of the yellow Singapore Far East Moon memorial rose created in Australia, named for the SS Vyner Brooke Australian Army Nurses and in memory of all Far East Prisoners of War and civilian internees.

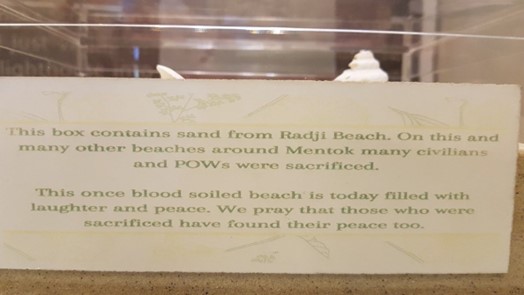

A glass box contains sand and shells from Radji Beach, with a label which reads : “This once blood-soiled beach is now filled with laughter and peace. We pray that those who were sacrificed have found their peace, too.” The prisoners who returned home suffered for many years, as did their families – we pray that they have also found peace.

Professor Gary Topping in Utah USA, Catholic archivist and biographer of American journalist William McDougall who later became a Priest and Monsignor, has written that it gladdens his heart to learn that Muntok can become a place of beauty and education and is no longer only a place of dread.

The Vice Regent of Muntok officiated at the opening of the Muntok Peace Museum. We were surprised and very touched when he suddenly began to sing in English some words from John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’:

Imagine no possessions, I wonder if you can,

No need for greed or hunger, A brotherhood of man.

Imagine all the people Sharing all the world…

You may say I’m a dreamer But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will live as one.

Many visitors to this website have been able to reconnect with other Prisoners’ families and it is hoped the work of uniting these families continues for many years to come. The Museum too is a work in progress and new items and information will always be welcome.

Some have joined to help the Muntok Red Cross and during Covid provided medical equipment and a Covid transport ambulance.

This work is ongoing.

Gordon Reis wrote in his prison camp diary that “Thoughts of our loved ones are our guiding stars.” We cannot change the past but we can remember and learn from it, be inspired by the courage of these prisoners, work to help others in their memory and try to create a more peaceful world now and in the future.