Muntok was used by the Japanese over two time periods: first for about a month from mid February to mid March 1942. And second from 19 September 1943 to March 1945 – one year and six months – during which 270 of the 960 internees met their deaths. Before that, between March 1942 and September 1943 the internees were held at Palembang. The map below shows these movements.

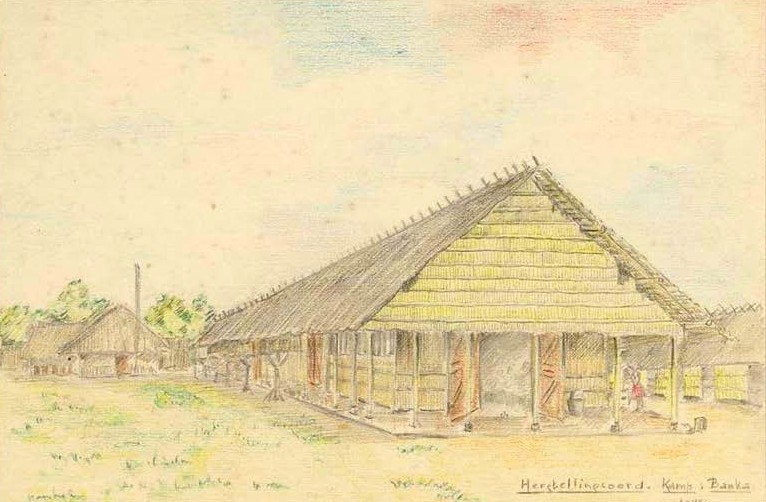

As in Palembang, two camps were created – one for the men (the jail) and an ‘atap’ camp for the women and children. This page examines the second and much lengthier time during which the jail and camp at Muntok were used. Much of the text below is from the work of Judy Balcombe.

The Second Period at Muntok 1943 – 1945

In the middle of September 1943, the Japanese took the male civilians that had been imprisoned in the Palembang bamboo and palm leaf ‘atap’ camp and placed them on to old boats on the Moesi River.

There they travelled along the slow, wide and familiar route, hungry, cramped, and uncomfortable. They reached the stretch of open sea, known as the Bangka Straits, where so many had been bombed and shipwrecked in February 1942.

When the boats reached Bangka Island, the men landed at the 600m long Muntok pier and then were marched through the town back to the grim and foreboding gates of the Muntok jail.

Originally built to house 200 local Bangka Island prisoners, now 639 men were crammed inside.

Once more, they slept crushed together on the sloping concrete slabs, like fish for sale in a market. Unlike a market, though, there were no fish to eat, only ever-decreasing measures of vitamin-poor white rice, flavoured with a few strings of vegetables and sometimes a tiny shred of meat. Sometimes the only food was a small bowl of watery rice, like glue, nick-named ‘ongle-ongle’, with no taste or nourishment. If not eaten, it was a useful paste for leg ulcers.

The human being is sustained by kindness, friendship, and hope but underpinning these is a fundamental need for nutrition. Without adequate requirements of calories, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and vitamins, health cannot be maintained or disease resisted.

Vitamin B1 deficiency, caused by eating husked white rather than brown rice, developed in many internees, causing Beriberi. This was of two forms – dry and wet. Dry Beriberi affected the function of nerves so that victims lost the ability to walk or to see. Wet Beriberi caused fluid to build up in the limbs, the abdomen, the lungs and around the heart. Arms and legs became swollen like tree trunks and the patients became unable to breathe, drowning in their own congestion.

Beriberi was first identified 4,500 years ago in China. It was well-known in Asia where white rice was a staple food; it was a condition which was therefore well -understood by the Japanese. Despite this, adequate food was never provided to the captives.

Infectious Dysentery, with frequent watery and blood -stained diarrhoea was another illness which afflicted the captives, robbing them of fluids, nutrition and strength.

Bangka Island was then and remains a Malarial infested area. Without quinine tablets or mosquito nets, the men began to suffer recurrent episodes. Some contracted the usually fatal cerebral Malaria – a few, including William McDougall, were very lucky to survive. Deadly attacks of ‘Bangka fever’ (possibly Dengue fever) also took their toll on the weakened and malnourished men.

The very sick and dying men were moved from the Muntok jail into the Tinwinning Hospital next door, reached by a barbed wire passageway. Here, although there was no medicine to treat them, the men were able to lie quietly, cared for by their fellow captives, including the Catholic Brothers interned with them. The Brothers were among those who volunteered to nurse the dying men; eleven Brothers became ill and died during this time. Death usually claimed the Tinwinning patients, who could have lived with adequate medical care.

In early June 1944 an additional 200 male internees entered the Muntok Jail from a prison camp at Pangkal Pinang to the East of Bangka Island; soon 900 men were crammed into the Muntok jail and Tinwinning coolie lines ‘hospital’. Deaths were carefully recorded – we know that 270 Dutch, British, and Australian men died in Muntok during this period of internment.

The Japanese, who had not looked after the men while they lived, permitted them to have funerals when they died. Rough bamboo coffins were provided and, while they had strength, their friends carried each body a mile up the hill to the Muntok Civil, Town or ‘Old Dutch’ cemetery.

Captain Seiki Kazue, the camp commandant, often donated a floral wreath for the occasion, although the internees felt the money would have been much better used to provide food and medicines for the living. The mourners held a brief service and sang the hymn ‘Abide with Me’ before walking slowly back along the tree lined boulevard to the jail.

American journalist William McDougall worked in the Tinwinning / Coolie Lines ‘hospital’ and morgue and kept detailed lists of all the men who died. The men’s graves in the cemetery were marked with wooden crosses and each plot was carefully recorded.

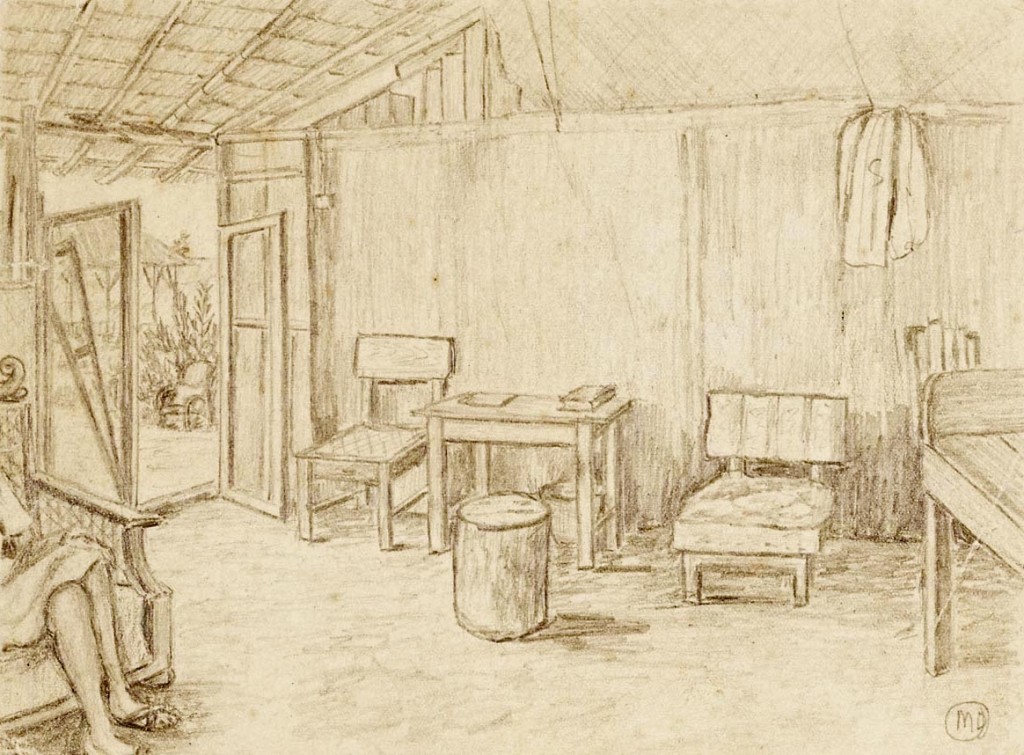

A plan of Muntok Jail and a pan of the Coolie Lines ‘Hospital’ were drawn by Theo Rottier and can be accessed HERE. The two buildings were adjacent to each other although today where the ‘Hospital’ was is a large empty space with two or three recently built bungalows on it. The block numbering also reflects that used by McDougall and others in their writings about their internment. Jock Brodie recalls the ‘hospital’ as consisting of:

…. five wards each about 40 feet long by 20 feet wide, and the beds were concrete platforms about 2 feet above the concrete floor. The buildings were quite good but of course had no hospital appointments. The premises had to get a name anyway and were called ‘Hospital’. Each ward had 25 patients, and very soon after opening each ward was filled to capacity. The wards were arranged one each for Malaria, Dysentery, Beri-Beri, Sores and Ulcers. T.B. etc. and one for the older men in the camp who required a certain amount of attention. Malaria was rampant in the camp at this time and with insufficient ‘Obat’ – medical supplies to ease the recurring fevers the condition of a great many weakened, and other forms of disease and trouble attacked them.

The men’s camp suffered an extremely heavy regime under the commandant captain Seki, especially with regard to systematic starvation and the withholding of medical care. The image below from the Australian War Museum shows the condition of Australian prisoners held in Thailand but it no doubt also reflects that found among the starving and diseased internees at Muntok of whom well over two hundred and fifty died.

The Women are Moved from Palembang to Muntok

The women internees remained in the atap huts in Palembang for some months. They were joined by 40 nuns from the closed Charitas hospital and women from other camps in Sumatra. The women tried hard to care for their children, coaxing them to eat the decayed or unappetising food and struggling to clothe them as they grew with the months and years. They attempted to educate their children, who found simple games to play in the dirt with sticks and stones.

On several occasions, Captain Seiki ordered all growing boys from the Women’s Camp to assemble in public and to pull down their pants. In this way, he judged which boys had begun puberty – these lads were told to say farewell to their Mothers immediately and were sent to the Men’s Camp the same day. The women and the boys were distraught – they did not know where the men were imprisoned, if their male relatives, if any, were still alive or whether Mothers and sons would meet again.

The boys were taken in trucks to the Moesi River and sent on boats to Muntok. Those boys without a relative in camp were given a male guardian from among the internees. This man would be replaced with another guardian if the first died. The Catholic priests and Brothers tried to teach the boys and some boys were confirmed in camp.

In November 1944, the women were moved from the Palembang Camp. They were taken again on the Moesi River in the same cramped boats on the twelve hour journey to Muntok. Reaching Bangka Island, they were left to lie overnight on the Muntok pier, without food or facilities. The following day they were taken to another bamboo and atap prison camp. Here they were placed, away from their husbands and sons confined in the Muntok jail. The place was called Kampong Menjelang and is where the Peace Museum can be found today.

At first the women believed that this camp was an improvement over Palembang – the huts were new and clean and a cool breeze blew through the surrounding trees. But the two years of increasing starvation and weakness had affected them all. Beriberi, Dysentery, Malaria, TB and tropical ulcers soon affected the women and took their toll.

The Nurses tried to care for the sick women and children in a bamboo and palm leaf ‘hospital’ hut but without medicines and facilities, little medical help could be given. 76 Dutch, British and Australian women died in Muntok and were buried by their friends in shallow graves dug by the internees under trees at the edge of the camp.

Often the dying women made a will, leaving their meagre possessions – a threadbare dress, patched blanket or broken comb to their close friends. At the end of October 1944 four women from PankerPinang joined the women at Muntok.

Unlike the men, who were enclosed in the concrete compound of the Muntok jail, the women lived surrounded by barbed wire. Conditions were generally better for the women than they were for the men. Those women who still had any possessions to trade could try to barter with local people brave enough to approach the wire fence at night. In this way, a precious engagement or wedding ring, treasured through internment, could sometimes be exchanged for a few quinine tablets for Malaria or a handful of Vitamin B-rich and lifesaving dried beans.

The penalties if caught trading were harsh. Prisoners were made to kneel in the hot sun for hours, without shade or water. Some local traders were punished severely and were not seen again, believed to have been killed.

A summary of the camps that the women and children were placed in along with some images of the artefacts made by the women has been prepared by Judy Balcombe can be read HERE.

Undoubtedly, the Japanese civilian internee camps did not share the genocidal ambitions of their Nazi counterparts, but the high death rates at Muntok, the occasional forced labor, mistreatment, starvation and denial of access to medical care has produced the notion of the Japanese as particularly “brutal” captors and of the survivors as inevitably traumatized by that experience.

To describe the starvation suffered by the internees, the devastation wrought by malaria, beri-beri, dysentery, and tropical ulcers, the completely inadequate medical facilities, the slappings, kickings, beatings, and hours spent standing beneath the blazing tropical sun – the almost unimaginable horror of the lives of the civilian internees and the extent of their mistreatment – should never be forgotten.

Below Changi prisoners soon after their liberation.

Camp records from Muntok show the following deaths for men from June to December 1944, with sometimes up to 6 deaths per day:

June, (14); July, (23); August, (21); September, (14); October, (30); November, (58); December, (33) (from internee Jock Brodie’s memoirs).

Another element of Japanese administration at Muntok (but not connected to the prison system) was the Tinwinning company building which was used as the headquarters of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Corp. which took over the tin mining operations on Muntok.

[Most of the above text was provided by Judy Balcombe. Thank you Judy.]

DEATH BY BERIBERI

Patients become severely dyspneic [difficulty breathing] and have violent palpitations of the heart and intense precordial agony [the precodium is the portion of the body over the heart and lower chest]. The patient is restless and tosses and turns violently from one side of the bed to the other. The patient moans and shrieks. His cry takes on a special character because of the coincident hoarseness and sometimes aphonia [loss of ability to speak]. He suffers from emotional disturbances and impaired sensory perception. He is often intensely thirsty but reacts to drinking by vomiting. He is anxious, his pupils are dilated, breathing is frequent and shallow. The patient prefers to lie rather than sit up in bed. The skin takes on a bluish color [cyanosis]. The liver is enlarged and tender. The heart is enlarged in all directions but mostly to the right. Heart murmurs can be heard and its action is tumultuous. Respiration is rough accompanied by whistling and toward the end abnormal rattling sounds can be heard which are at first dry and then later moist [rales]. Gross edema may occur, especially of the legs, that is when the body fills with fluid. The patient dies intensely dyspneic [having difficulty breathing] and usually fully conscious.