Introduction

The civilian internees were moved to and from various camps at various dates. A two page PDF summarizing the names of the civilians’ camps, their locations, and dates of occupation can be viewed HERE.

Initially at Palembang civilian and military personnel were mixed together but the Japanese soon sorted the two groups out and sent each to separate camps. Civilian men were sent to the jail in the middle of the town, women and children to former Dutch residences, while the military were separated into three camps: Mulo School, Chung Wa School (sometimes referred to as ‘The Chinese School’), and Sungei Geron (Sungei Ron) near the Pladjoe Golf Course.

This website follows the lives (and many deaths) of the civilian internees but it would be unreasonable to ignore the military prisoners whose lives and deaths at Palembang were very similar to those of their civilian compatriots. Information on the military camps is sparse right now but as more is known it will be added to the end of this page.

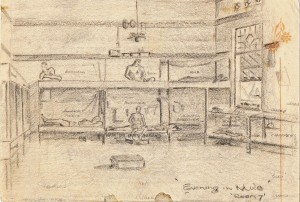

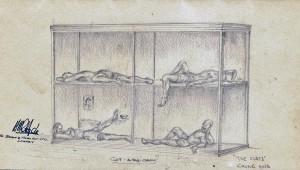

Many of the illustrations on this page were by William Bourke who, as a military man (Royal New Zealand Naval Volunteer Reserve), was imprisoned at both the Mulo and Chung Wa school camps. The text below is based on the work of Judy Balcombe.

Palembang, April 1942

After 4-6 weeks in Muntok, on Bangka Island, the men, women and children were transported by small boats across the Bangka Straits to the island of Sumatra. Here they travelled up the wide Moesi River to Palembang. Although not far, the journey lasted more than twelve hours and was very uncomfortable. A handful of cold rice and sips of cold tea were all their sustenance.

There was no protection from the sun except in the oil-reeking hold. The only toilet facility was a wooden board suspended high above the water – the prisoners had to disrobe and relieve themselves in full view. The women’s friends tried to shield them with clothing for privacy and Singapore’s Cathedral organist cut a hole in the seat of a chair to form a makeshift lavatory and give the women some comfort.

They did not know they would make this dreadful trip several times more during their years of imprisonment – each time becoming increasingly more ill and frail and having lost many of their friends to sickness and starvation.

Before its capture by the Japanese, the city had come under heavy Japanese bombing and shelling and the retreating Allied army had adopted a ‘scorched earth’ policy toward the nearby oil refinery at Pladjoe so the town was a scene of devastation when the prisoners arrived.

In Palembang, the captives were first taken to a school at Bukit Besar, near the centre of the city. The British and Australian male soldiers had arrived before the women and had prepared a hot meal for them – their first proper food in weeks. Here, the civilians and soldiers were held for several days. After this time, they were separated – the soldiers were imprisoned in the former Mulo and Chung Wha schools and the civilian women and children taken to abandoned Dutch cottages in a guarded compound surrounded by barbed wire. The civilian men were confined in the Palembang jail.

A group of soldiers and interned civilians was taken by the Japanese to work at the local oil fields at Pladjoe on the Moesi River, already heavily bombed by the Allies. The captives were made to load ships with oil and to restore the damaged airfields. The work was very hard and the days long. The food and conditions were poor and dysentery soon killed several men. Their friends, devoid of all the comforts of life, said some simple prayers and burnt the bodies on the air fields.

Irenelaan, Palembang 1942 -3

The women were moved from the first cottages to another group of houses, also surrounded by barbed wire. A sentry box stood at each corner and there was a guard house at the gate. Here the Japanese guards supervised all their activities. There was no privacy, even for bathing or sleep – the guards watched as the women washed and lifted their bedcovers to look at their bodies during the night.

The women were forced to bow to the Japanese and to line up for roll calls, known as ‘Tenko’ for many hours in the hot sun. They were slapped and beaten for any perceived transgressions.

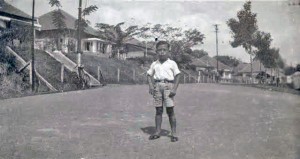

The women struggled to preserve some semblance of order while enclosed in the Dutch Houses Camp, which they named ‘Irenelaan’ after one of the streets where they lived. The Palembang Camp streets, Irenelaan and Bernhardlaan were had been named after the Dutch Princess and Prince.

Crowded thirty people to a house and ten to adjoining garages, the women formed small cooking groups, or kongsies. They worked hard, chopping wood and cooking the meagre rations of rice, scant vegetables and nearly invisible, decaying meat.

They made use of every article left behind by the original inhabitants, who had fled earlier to Java. A bowl, a cracked plate, a discarded stove thrown into the garden waste all became precious and valued items. A baby’s cot served as a bed for one small nurse until it was more needed for firewood. The backs of discarded photographs were converted into playing cards.

Supplies were brought into the camp in trucks by the Japanese. The rotten vegetables and a slab of stinking meat to feed the whole camp were flung out onto the hot and dusty road to be collected. There was no soap and no modern facilities but somehow these women, who only weeks before had had their own homes and servants, managed to wash and keep clean and care for themselves and their children.

The internees made the most of the little they had and shared whenever possible. Reverend Vic Wardle from the Men’s Camp had brought some of his wife’s and daughter’s clothes from Singapore, hoping to meet them – he sent these and items of his own clothing to the Women’s Camp. Mrs Mary Brown, who had reached Muntok on a raft from the Vyner Brooke nearly-naked, made a dress for herself from the Reverend’s striped pyjamas. She created a hat from a discarded umbrella and made hats for others from bamboo and dried grass. Other women had ‘borrowed’ sarongs from an abandoned hut when they had landed without clothing on the beach.

The women had to use all of their resources to survive. They made pieces of wood into rough sandals to help them to walk through the foul mud and the latrine effluent, which flooded in the torrential rain.

The camp toilets comprised open drains with no running water. It was necessary for volunteers to scoop faeces from the drains into buckets with coconut shells, trying to reduce the risk of flies and disease. The Australian nurses and other brave women volunteered to perform this foul and unhealthy task.

The 2/10 Australian General Hospital (AGH) were placed in house 6, while nurses from 2/13 AGH and 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station were in house 7.

In addition to the British and Australian evacuees from Singapore, many Dutch people who had lived in Sumatra were also interned in Palembang. Seized from their homes by the Japanese, these people had been brought into the prison camps in trucks. Unlike the bombed and shipwrecked evacuees, the Dutch often had significant possessions, including clothing, bedding, furniture, food and money.

The other penniless internees were sometimes able to work for the Dutch – washing clothes, cooking, chopping wood, cutting hair or minding children – for a few coins. They were then able to try to buy a little extra food from local shop-keepers occasionally allowed into the camp or else at great risk to both seller and purchaser from illegal traders who came up the barbed wire.

Charitas Hospital, Palembang 1942 -43

Despite the internees’ struggles to remain healthy, some inevitably became unwell. In the early months of internment, the Japanese permitted a number of patients to be taken by truck to the nearby Charitas Catholic Hospital. Here the doctors and nursing nuns attempted to care for the sick. The nuns kept many patients in hospital longer than necessary, to build up their strength and to try to reduce their risk of dying when they returned to camp.

In addition to providing medical care, the doctors and nuns tried to schedule patients’ appointments to allow husbands and wives to meet briefly in hospital – this was often the first that each knew the other was still alive. Patients returning to camp were able to bring news of other internees and sometimes to smuggle medicines, messages and money back into camp. Australian Nurse Mavis Hannah described after the War how she had smuggled letters inside a sanitary pad next to her skin.

The Japanese suddenly closed the Charitas Hospital in 1943, suspecting the staff of anti-Japanese behaviour and opened the new Charitas Hospital. Mother Alocoque and her staff hid medicine and instruments from the old hospital under their robes to use in the new premises. Dr Tekelenburg was sent to a severe military prison at Soengeiliat on the east of Bangka Island. Together with most inmates there, he died there. Dr Tekelenburg was a surgeon and it was said that his hands had been cut off.

Charitas Hospital’s Dr Ziesel and nine others were beheaded. Reverend Mother Alocoque was tortured and sent to a military prison where she knelt praying and would not speak to her captors; she survived the War. The remaining nursing nuns were interned in Palembang Women’s Camp, where they continued to try to care for the captive women and children. Mother Alocoque and the nuns received a medal from England’s King George 6th after the War, kept in the museum at Charitas today.

The Japanese took control of the Charitas buildings and used them for military purposes. The building commanded a clear view down to the Moesi River.

Palembang 1942 – 1943

Months and years passed. The physical condition of the women and children worsened as they continued to be deprived of food and medicine. They still tried, where possible, to maintain their spirits – they made birthday cards from improvised materials and gave one another gifts of small cakes made from baked ground rice and coconut. They relished simple pleasures such as the beauty of a jungle flower.

Margaret Dryburgh, a Presbyterian missionary, wrote poems and made cards to cheer the women and drew several accurate pictures of their camps.

The women used any available material to clothe themselves. Curtaining, black-out cloth or donated pieces of the nuns’ long habits were all used to make shorts and small tops to preserve their modesty.

They tried to fill any spare time left after their many chores were done and their children cared for. A few coloured threads were pulled from their tattered clothes and used to create small embroideries, a few of which survive. A precious sewing needle was passed from person to person.

The backs of photos left behind in the Dutch houses were used to make playing cards. Some women smoothed and polished scraps of wood to create tiles for mah-jong sets. They were not frivolous but hoped, by playing games, to distract themselves and their friends from worry and from hunger for a few precious moments.

In Palembang, the Japanese soldiers wanted to start an officers’ club in one of the Dutch Camp houses and tried to persuade the women to work there. The women were very alarmed and tried to discourage the men by dirtying their faces and coughing, pretending to have TB. Fortunately, the plan was eventually abandoned.

The following women died at Palembang before the move to Muntok in November 1944:

The following women died at Palembang before all the women were rounded up and sent over to Muntok on Bangka Island in November 1944.

WARMAN Mrs M. widow of Stephen. One of the first internees to die on 9.3.42.

TEELING Mrs Beatrice.Daughter of Regina & Joseph Anthony. Died 10.6.42.

ANTHONY, Mrs Regina, mother of the above. Died 16.9.42 [85].

ROBERTS, Elizabeth Louise ‘Freda’ Roberts, daughter of John Hazelwood. Died on 21.5.42 [50] at the Andreashim Hospital, Palembang.

MELLOR Mrs Mary Ellen Wife of H.L. Died 4.9.42 [76].

LAYLAND, Mrs Kathleen Minnes. Died 12.5.43 [49] at Charitas Catholic Hospital.

ANDERSON, Mrs Frances Mary Arkcoll. Wife of William from Penang. Died 5.3.44 [46].

MACLENNAN Mrs Mary M. Wife of Kenneth. Died 5.5.44 [46].

CURRAN SHARPE, Rhoda Elizabeth ‘Bet’, the daughter of William and Caroline Flint, of London. Died 11.5.44 [57].

GODLEY Mrs Zara Valda Mari. Died 7.6.44 [40].

OLDHAM Sally ‘Florris’ or ‘Florrie’. Died 19.6.44 [51].

GURR, Mrs Grace Naomi. Died 27.7.44 [35].

ISMAIL Mrs Vartouh ‘Peggy’. Died 17.10.44[60].

LAYBOURNE, Mrs Gladys Irene. Died 28.10.44 [53].

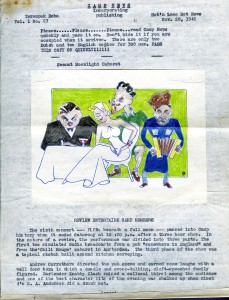

Palembang Jail, 1942 – 1943, ‘Camp News’

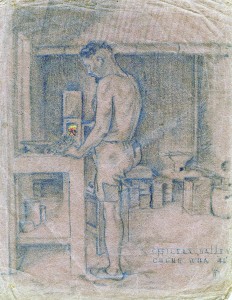

The male internees, meanwhile, strove to remain alive in the Palembang jail. The Dutch and British elected respective camp leaders and formed committees to organize cooking, washing and sanitation.

A magazine, Camp News was produced while paper and the men’s strength lasted; it was edited and typed by American journalist, William McDougall and William Probyn Allen.

4 copies of the magazine, with coloured illustrations, 2 in English and 2 in Dutch, circulated among the 308 men; they were quickly read and passed on. Articles concerning camp activities, gossip, details of church services, recipes and humour were included, aiming to inform, entertain and while away the long hours. A few possessions were offered for sale; a quiz offered a first prize of a fried egg.

The men tried to relieve their boredom with lectures, foreign language and music lessons, concerts and a badminton match. Camp News tells us that a number of men participated in the concerts, devising costumes and skits from their few resources. Songs, sketches and ditties all helped to distract the internees from their otherwise grim and dismal lives.

Donald Pratt was one concert member much appreciated by the audience. In real life, he was the nephew of Hollywood horror actor, Boris Karloff.

William McDougall buried the pages of Camp News in bottles and cans along the foundations of a camp building when a pipe was being laid. He was able to retrieve the intact pages after the War. The copies that McDougall managed to retrieve can be read HERE.

Below are some lines from Camp News where William McDougall quotes from a poem popularised in a war-time speech by Winston Churchill. The beautiful words must have encouraged the internees to hope for better times to come.

The words were later set to music by the interned Muntok priest, Father Bakker and given to Churchill and to Dutch Queen Wilhelmina after the War.

And not by Eastern Windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

(From Say not the Struggle nought Availeth By Arthur Hugh Clough)

By Eastern Windows was later the title of McDougall’s book describing the men’s long and difficult internment years.

Co-editor of Camp News, William Probyn Allen wrote following lines in a poem addressed to his wife at Christmas 1942. He died on 25th March, 1945 at Belalau Men’s Camp in Sumatra. They did not meet again.

….Last year I hung a stocking, childlike, by your bed

While you were sleeping, but this year my thoughts instead

And prayers and wishes to the stars and round moon spoken,

Are all the gifts that I can send to you for token

Of all the joy these is between us, come what may.

Have faith, my love, although the night is dark, the day

Will break and peace and good will come to men at last.

God bless and keep you always.

The Palembang jail became increasingly overcrowded as more internees were brought in from elsewhere. The Japanese therefore decided the male captives should build a new camp at Poentjak Sekoening, (‘Yellow Peak’, from yellow tree blossoms), half an hour’s walk from the jail, in a field close to the Women’s Camp. For several months, a group of fifty men marched from the jail to work on the new camp site.

Many men asked to join the work party to experience the freedom of walking outside, to gain the exercise and to try to barter with the local people for food. The men laboured with local workers to build the new camp of bamboo and atap (palm leaf) huts. The finished camp would be surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, with guards.

The working party passed near the women’s houses each day. Sometimes the women climbed onto a high wall and waved and called to the men as they walked past. Too far away to speak, they could at least recognise one another and know that their loved ones were alive or convey this information to friends.

Christmas 1942

On Christmas Eve 1942, as the men approached the standing women, there was no sound and the waiting women were still. The men halted, worried that something was wrong. Suddenly women’s voices arouse from the wall, singing in unison the beautiful Christmas carols, O Come All Ye Faithful and Silent Night. The men paused and listened in silence. Even the guards were moved by the music and allowed the men to walk slowly and absorb the unexpected offering.

The men’s choir, led by Muntok’s interned Catholic priest Father Bakker, joined the working party on Boxing Day 1942 and reciprocated by singing carols to the waiting women. The guards would not allow them to stop but the men managed to take their time walking past the wall, reaching out to their wives, children and friends with their heartfelt gift of song.

On Christmas Day, church services were held in English and Dutch. Carefully hoarded ingredients were used to make a special meal and small gifts were exchanged. The women made toffee from local sugar and sent pieces to male internees who had no family in the Women’s camp.

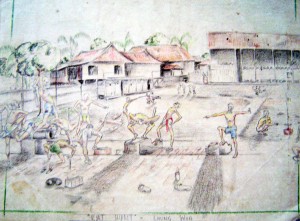

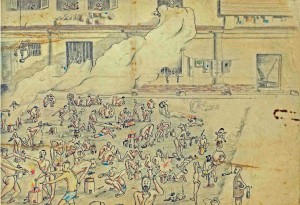

The Palembang Jail, which formed the Men’s Prison Camp for a year, comprised 4 double-storey blocks with a large central exercise yard. There were a number of Australian and New Zealand jockeys in Camp, formerly from trainer Mr Hobbs’ stables in KL. Around Melbourne Cup Day, it was decided to hold a racing event in the Jail. The bigger internees were the horses and they carried the jockeys and smaller prisoners. Neal Hobbs was also chosen. He had spent many weeks in hospital with dysentery and was much lighter than usual. The betting was fierce, and the spectators yelled and cheered their chosen ‘horses’ as they careered across the yard. Finally, the entertainment was over. Punters received their winnings and the bookmaker’s profits, 30 Dutch Guilders, were sent to the Women’s Camp to help buy them a decent Christmas dinner.

Atap Barracks Camp, Palembang

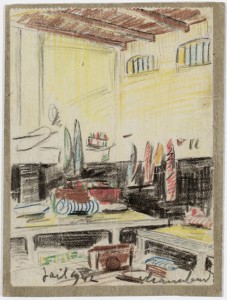

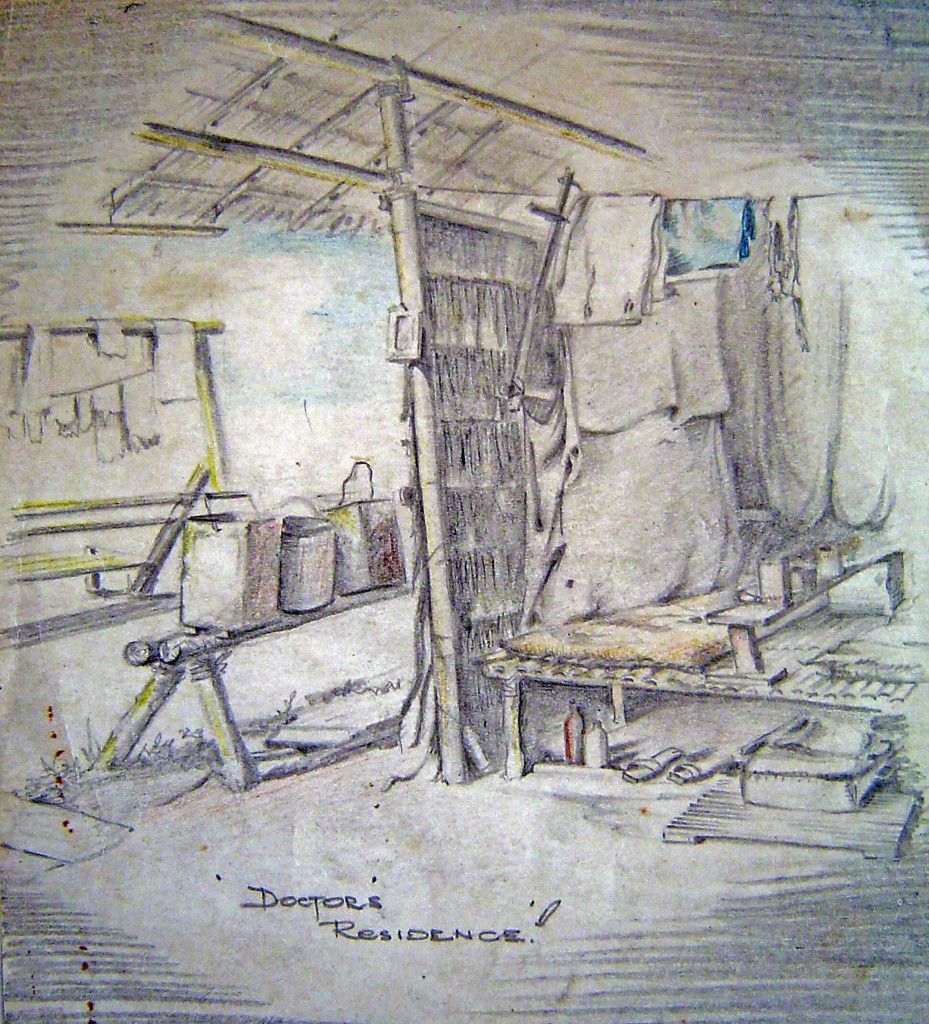

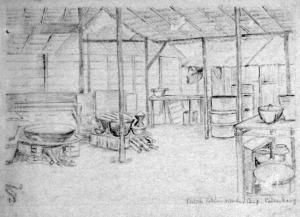

The bamboo and palm leaf huts were completed in January 1943 and the men left the Palembang jail to move into their new camp. There was still inadequate food and sanitation and now their situation was worsened by a shortage of fresh water for drinking and washing. The Men had to dig a deep well and the water was brown and muddy, needing to be boiled.

New problems arose – exposure to rain and tropical storms through the palm-leaf roofs, rats and lice living in the roughly-hewn huts and overflowing faeces from the drains. Water was rationed and mud was everywhere.

The men continued to hope that the war would end soon or that they would be repatriated home in exchange for Japanese prisoners. But this was not to be. In September 1943, the men were told they were about to leave the bamboo and atap barracks camp but were not told their destination. Believing that their captors were going to live in the huts, the internees caused what damage they could and flung rough plank furniture down into the well.

The Japanese were not going to live in the camp, however. The new inhabitants were the women internees from the nearby Dutch houses. Their conditions had been cramped before but the Women were now dismayed to find the bamboo and palm leaf huts not only primitive but in such a state of disrepair.

(see also The Women’s Vocal Orchestra page)

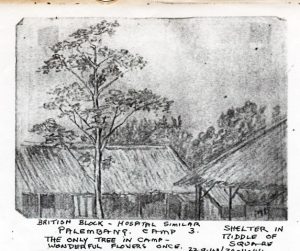

THE MILITARY CAMPS AT PALEMBANG

As noted above there were three military camps at Palembang: Mulo School, Chung Wa School, and Sungei / Soengei Geron, near the Pladjoe Golf Course. It is believed that the two school camps were later closed by the Japanese and all military personnel ended up in Sungei/Songei Geron (to be confirmed).

The Sungei / Soengei Geron camp was mostly burnt to the ground at the end of the war after all had been evacuated it was so bad. Below is a photo of the rat and lice-infested “hospital” which the Japanese wanted to burn down but the prisoners would not allow it until the relieving allied forces had seen it for themselves.

Many members of the military were in fact civilian volunteers and bore the initials RNVR or MRNVR, etc. after their names. Like their full time counterparts the volunteers wore a uniform, carried weapons, underwent training, and fought the Japanese but, they were not enlisted soldiers or sailors. As a result they were not entitled to any compensation after the War or even a burial.

On the list of all the internees on this website we have counted approximately 12 active members of the volunteer force. The Japanese for the most part treated the volunteer force as military personnel and as a result they were imprisoned at the Mulo and Chung Wa schools. However a few ended up at Muntok with the civilians (See Robert Morris, William Nessfield). So the distinction between military and civilian was not always clearly maintained when it came to the volunteers.

Title: Liberated Allied and Australian Prisoners of War from Palembang – Sumatra, (one of the most notorious Japanese prison camps) relate their experiences to a British War Correspondent in Singapore. Contributor: Argus (Melbourne, Vic.).

The Soengei Geron camp consisted of barracks of bamboo and atap and was surrounded by barbed wire; it was in the midst of Japan’s military facilities (airport, encampments, searchlights, anti-aircraft guns).