Muntok was used by the Japanese over two time periods: first for about a month from mid February to mid March 1942. And second from 19 September 1943 to March 1945 – one year and six months – during which 270 of the 960 internees met their deaths. Between March 1942 and September 1943 the internees were held at Palembang. This page deals with the one month in 1942.

The First Period at Muntok

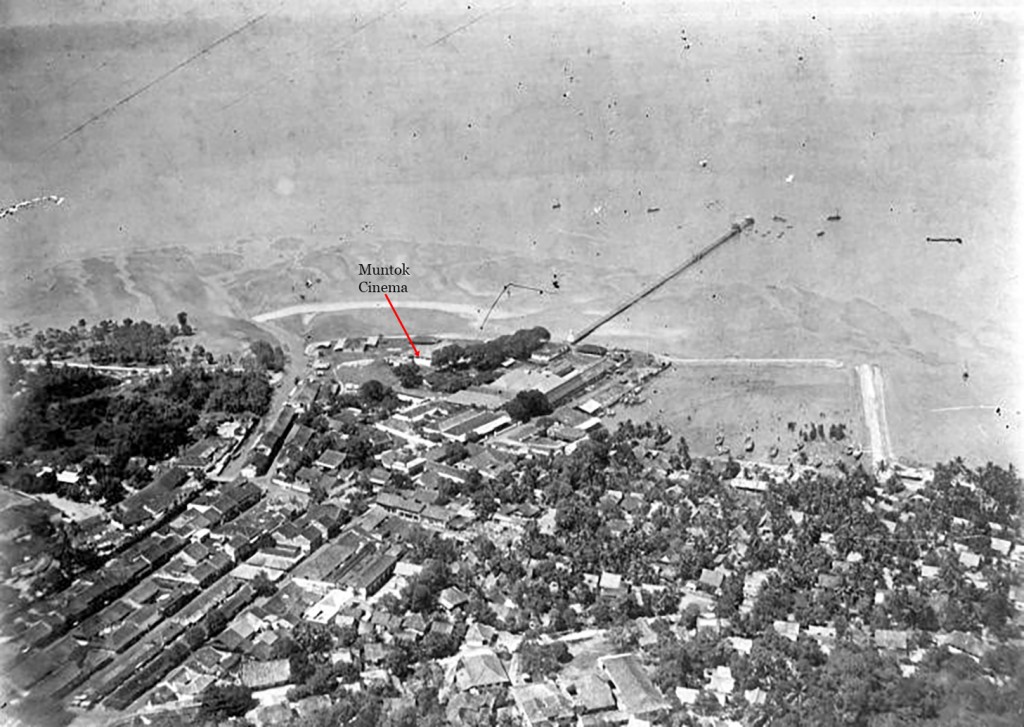

During the first time period, when the shipwrecked evacuees came to shore in February 1942, they were ordered by Japanese soldiers to walk along the 600m of the Muntok harbor wharf / jetty to the cinema (The Alhambra) and Customs House to be processed and taken from there to the high stone walls of the Muntok jail.

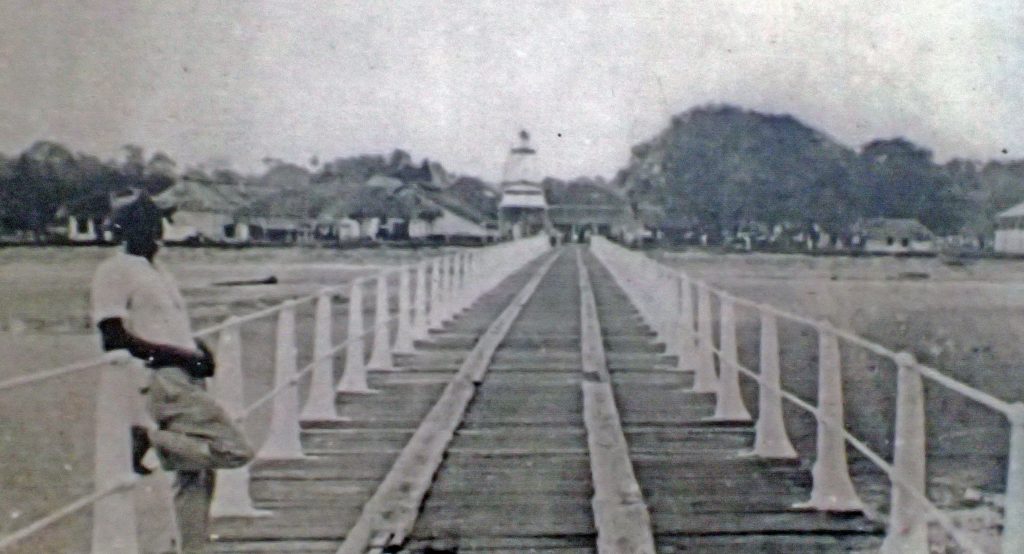

The jetty along which the internees were marched no longer exists but this rather blurred photo below taken in the 1930s gives one an idea of what the prisoners faced:

A group of Chinese workers, press-ganged by the Japanese from streets of Hong Kong, had been shipped to Muntok to work in the local tin mines. The Chinese labourers were ill and poorly treated and many died where they lay in the coolie lines (huts) next to the jail. Two workers went mad and leapt onto the jail roof. A Japanese guard aimed his rifle and shot one man dead – the other, faced with no choice, was ordered down.

The captives huddled together in the jail. A single tap provided drips of water during some hours of the day. Long queues formed to fill scavenged drinking vessels. One man had a small tobacco tin to drink from; another had half a coconut shell found on a rubbish heap. Their food was buckets of dirty rice, evenly divided to provide each person with a small handful. A few strands of vegetables added flavour if not nutrition; meat, rotten and the size of a thumbnail was much-prized but seldom seen.

At night, the prisoners lay shoulder to shoulder on cold and sloping concrete slabs. If one person turned over, all the others were disturbed.

The nurses confined in the jail tried to help their wounded fellows. Some had all the skin stripped from their hands as they slid down ropes into the water, so wounded and painful that they could not feed themselves. Others had been burnt and blistered by the sun while drifting on the rafts, and yet others had been wounded by shrapnel, burning oil and gun fire.

Jock Brodie writing in his diary describes the conditions:

“There were hundreds of bags of pepper on which the majority of the British. prisoners slept. The prison had been shelled and bombed …. The place was in a filthy condition with a 1/2” water supply and no sanitation. In addition about 600 Chinese coolies, occupied half of the place. They were of a very poor type having been pressed ganged from Hong Kong …. out of the 600, it was difficult for the Japs to muster 100 men for work, so terrible was the suffering of these helpless Chinese from sores and disease. It was a daily occurrence during the time we were in this place to see 2 or 3 Chinese coolies unceremoniously carried away to their last resting place shrouded in old [pepper] bags. Those who were about to die seemed to crawl out into the open, and unattended by the Japs or their countrymen quickly ended their miserable existence.”

Gordon Reis in his diary wrote:

“We arrived at Muntok jetty where it started to rain and before we were under shelter it must have been at least one and a half hours. We were marched to the Cinema and then counted and allowed in where we totaled several hundreds — civilians and all the various forces. We were searched on entry but having nothing – I lost nothing. We were then allowed to sit on upright chairs and after dark an odd hurricane light was lit and the sentries were amongst us throughout the whole night. Latrines were cut outside in the open and late at night we had a meal of rice and some tinned food from some of the captured ships. I ate my rice out of a vegetable tin and used part of the lid as a spoon. I hardly slept during the night but managed for a time to lie down on cement floor beside a man who had an overcoat ….”

Soon after reaching Muntok jail, the captive men were taken in trucks in the darkness to a field. Facing the men were deep trenches – as they stood in front of the holes, they believed they were about to be shot and buried.

Instead, the Japanese ordered them to fill the pits, dug earlier by Dutch, British and Australian soldiers to disrupt an aerodrome and prevent its use. The men were forced from their slumbers each day at 4.30am and made to work until 11 pm, labouring by the light of flares.

This aerodrome had been established for the Australian flyer Sir Ross Smith in 1919 and used by many pioneer aviators, including Mrs Lores Bonney who landed in Muntok in 1937 to escape a storm. Mrs Bonney received the Order of the British Empire as the first woman to fly around Australia and from Australia to England. Now the air field was being repaired by slaves.

After processing the prisoners, which took about a month, the Japanese next transported them by boat across to the mainland of Sumatra and to the town of Palembang.

During their time at Muntok one of the internees, Vivian Bowden, was shot and killed by the Japanese guards. To read more about the circumstances that led up to Bowden’s ‘execution’ follow this link.