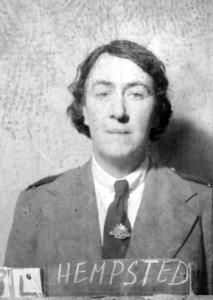

Pauline Blanche Hempsted, was born in 1908, at Brisbane. She was the daughter of Percy and Bertha Louisa Hempsted, of East Graceville, Queensland, Australia. Pauline was an Australian Army Nursing Sister (AANS). She died at Muntok on 19 March 1945 aged 36. Her grave moved after the war to the Jakarta War Cemetery DWC-1 Plot 5 Row 6 Grave 5.

Pauline Blanche Hempsted, was born in 1908, at Brisbane. She was the daughter of Percy and Bertha Louisa Hempsted, of East Graceville, Queensland, Australia. Pauline was an Australian Army Nursing Sister (AANS). She died at Muntok on 19 March 1945 aged 36. Her grave moved after the war to the Jakarta War Cemetery DWC-1 Plot 5 Row 6 Grave 5.

The following is extracted from Sarah Fulford’s Training, ethos, camaraderie and endurance of World War Two Australian POW nurses. [Note the spelling of Blanche’s last name is Hempsted in her enlistment photo, but she is referred to as Hempstead in the memoirs of her fellow captives].

The accounts in the nurses’ memoirs include a humorous explanation of events despite the serious situation the women were in. Blanche Hempstead is a specific focus in a number of the stories. They had agreed as a group to not accept liquor from the Japanese. When one enquired what Australian women drank, Hempstead who “…could drink and swear with the best of the cattle drivers, replied in a sweetly innocent voice that ‘Australian girls were nice and did not drink alcohol…’ ” this statement bringing much mirth from the nurses who heard it, “if Vivian had not controlled herself she would have burst out laughing at this ridiculous statement”.

Jessie Simons also referred to Hempstead’s reaction. “The girl addressed had often drunk too much of what was not good for her…. Despite the gravity of our plight I nearly burst out laughing as I caught her eye”.

The women refused the Japanese advances throughout the night and the majority were sent home with a small group forced to stay. They had been chosen before the night began by the nurses for their apparent ability to outwit the Japanese. The memoirs maintain that this group was finally allowed to return to the other nurses without incident. Blanche Hempstead had a cough and pretended to have tuberculosis, barking and barking until the Japanese sent her home.

Vivian Bullwinkel recorded another altercation in which Blanche Hempstead told one of the civilians that she needed to: “…belt up or there would be a bloody big blue”. Bullwinkel emphasised the group comradeship when she described Nesta James coming to the defence of Hempstead when they were questioned by their captors over the incident. James told the Japanese guard that the Australian women would not be bullied by other internees.

The cough Blanche Hempstead pretended was tuberculosis at the beginning of internment probably indicated she had cancer and she was the next to die. Through her larrikinism, Hempstead always brought laughter to their difficult existence. She was known for her hard work, which undoubtedly hastened her death. When she realised that death was inevitable, she apologised to her friends for taking so long to die. Hempstead’s apology is reiterated in a number of the nurses’ stories. “In the end she must have known she would not get well, because she apologised to one of her friends who was sitting there with her for taking so long to die. She died half an hour later”.

The following is taken from: The Story of 13th Australian General Hospital; 8th Division; 2nd A. I. F.; 1941 – 1945:

When twenty casualties were unloaded from ambulances on February 1st (1942) very late at night, diagnosed as suffering from a variety of fevers caught in the swamps and jungles, S/N Hempsted immediately took them under her wing and administered not only prescribed medicines but much home-spun common sense. Patients were there to be made fit and well as soon as possible and Nurse Hempsted endeavoured to gain patient co-operation to make this a reality.

S/N QFX 22714 Pauline Blanche Hempsted, passed away on the 19th March, 1945. Puffed-up with Beri-beri which eventually reached the heart, this hard working nurse could survive no longer.

The funerals of the nurses were carried out with full military honours. The sisters, wearing their tattered uniforms, slow-marched behind the coffins. Even the Japanese realised that the occasions were of great significance and often stood to attention as their mark of respect.