Gordon Burt, OBE, was born in 1899 at Dunedin, New Zealand. He was apprenticed to the family firm A. & T. Burt. He went to the UK in 1923 to work for Metropolitan Vickers & study at Liverpool University. He was the Chief Engineer in Worsley’s 1925 Polar Expedition. On his return he worked in Wellington, (NZ) then returned to UK. He went to Singapore from APC London in 1937. He was employed as Assistant Lubrication Engineer for the Asiatic Petroleum Company, Shell House, Collyer Quay, Singapore. In 1938 he joined the Singapore Volunteer Armoured Car Company and was awarded the O.B.E. in January 1942

In 1938 he married Maud Rohrbach. Their daughter Jocelyn was born in 1940 in Singapore. Below from the Straits Times, 26 June, 1938.

Maud and Jocelyn were evacuated on the Gorgon, arriving Fremantle Western Australia on 20th February 1942 and then to UK. They returned to New Zealand in 1947.

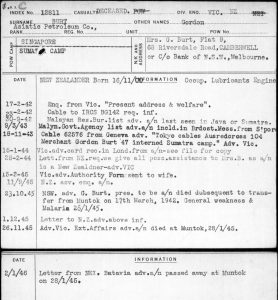

Gordon escaped from Singapore on board the launch Siang Wo, acting as the ship’s Chief Engineer. He was captured and held at Palembang and then Muntok. He died in captivity 28th January 1945, aged 46 years, at Muntok (see graves page). McDougall wrote in his diary: ‘One of the toughest men, physically, in camp, boundless energy, indefatigable student, he learned & mastered Spanish in camp…Only survivor of launch shelled in Moesi River, threatened with execution after capture… his ambition to play in Camp orchestra never materialised – only once did he play in it. He wanted to surprise his wife with the guitar & Spanish. Now he’s dead – fever, beri beri, starvation.’

Gordon’s captivity diary is held by National Library of Australia NLA MS9038. The Library describes the diary as follows: Manuscript diary, giving a contemporary descriptive account of Gordon Burt’s experiences from December 1941 to September 1944 (in pencil on 32 pages and 5 fragments of paper). Burt describes the fall of Singapore in February 1942, his escape and subsequent capture by the Japanese and his internment in South Sumatra at Palembang Military Barracks Prison; Palembang Military POW Camp, Palembang Native Criminal Jail and Muntok POW Camp on Banka Island.

Burt records, “As each page was written it was sewn into my trousers as we never knew from day to day when the ‘Kampey’ would make one of their surprise visits and ruthlessly search for firearms, maps, papers, or any incriminating documents”. The collection also includes letters (including those mentioned in the diary which he received in the POW camp), photographs, newspaper clippings and Burt’s Order of the British Empire (OBE) medal.

William McDougall mentions Gordon Burt a number of times in his book ‘By Eastern Windows’. The following have been extracted from that book:

I opened the door and walked out into the small area behind the hospital fence. A man was at the bath tank cleaning his teeth with a large, black stiff brush of a type not generally associated with teeth.

“How does it taste?” I asked.

“Inky,” he replied.

“Where’s the typewriter it came with?”

“In my cell. Fellow brought it in with him.”

The brush wielder, a sunburned man clad only in a pair of black shorts held up with a drawstring, introduced himself.

“Burt,” he said. “Gordon Burt. Late of His Majesty’s Engineers, Malaya.”

Burt was a gaunt but wiry New Zealander with little knots of muscle where they would do the most good. Thick black eyebrows and a hawk nose frowned over a stubby black beard. He finished his tooth-cleaning operations, removed his shorts and started splashing water over himself.

“My third bath this morning,” he shouted. “I can’t get too much of this water.”

Burt said he was the only survivor of a group of British engineers who, on the last leg of a run from Singapore to Palembang, were chugging up the Moesi river in a launch when they ran smack into a Japanese gunboat. That was their first intimation that Palembang had been captured.

The launch was blown out of the water. Uninjured, Burt swam to shore, pulled himself up in the weeds and lay there until sundown. He hid for ten days in the jungle but hunger and mosquitoes finally drove him out. He waved down another Japanese river craft and was taken to Palembang, stripped naked and left for two weeks in a guardhouse cell. Finally, he was given the pair of black shorts he was wearing and brought to the jail.

The clangety-clang-clang of roll call bell interrupted our conversation.

‘‘Food,” said Burt, “have to grab my dish and get in line.”

He jumped into his shorts without bothering to dry him-self, dashed through the fence gate which was left open so men could use the bath tank, and ran toward his cell.

Part 2

Next morning after roll call prisoners were ordered to line up in the yard, fully clothed, for inspection. Fully clothed meant shirts, shorts or long trousers and footgear of whatever description we possessed. New Zealander Burt stood in line wearing only his brief, black shorts. A guard, through the interpreter, ordered him to go and get dressed.

“I have nothing to put on,” Burt said. “The blighters threw me in here just like this. Tell them I have no shirt or pants or even shoes.”

The guard commander swelled up and chattered angrily. A fellow prisoner offered to lend a shirt.

“No,” said Burt, “I want one of my own. They can give me a shirt if they will.”

The commander ordered Burt to borrow the necessary garment or be beaten on the spot. Burt capitulated but, because he was still barefooted, was ordered to change places with a man in a back row.

Part 3

Another steady customer [for rolled cigarettes] was the New Zealander, Burt, who developed our first colossal case of “Palembang Bottom,” Burt was the case history on which we based our subsequent treatment of that ailment and by which we proved the efficacy of hot water, the sun and Gentian Violet, in the order named.

Palembang Bottom usually started with small blisters which developed into running sores where one sits down. [Reis in his diary describes it as: ‘ … eruptions, sores, pus, itch, irritations…’].

We experimented on Burt for a long time before we finally hit the curing combination. In the beginning nothing worked. Sulphur, salicylate, coconut oil, poultices of various kinds and descriptions were of no avail.

‘‘What am I going to do. Doc?” I asked West in despair one morning when Burt presented his bottom for another treatment.

“You’ve got to do something,” Burt chimed in. “My wife will never believe me if I tell her I got these just sitting in a jail,”

Doc had an idea.

“Burt,” he said, “go sit in a bucket of hot water.”

Faithfully, Burt followed instructions. Since we had only two kinds of receptacles for holding water, five gallon kerosene tins and ordinary pails, neither of which had the necessary staunchness or circumference, Burt’s gymnastics dunking his backside each morning were something to behold. Audience reaction was terrific. Within a week Burt’s back-side had improved remarkably, but it reached a certain stage of cure and there remained. Something else was needed.

Doc’s next idea was sunshine.

“Do your soaking early,” he told Burt, “and then take a sunbath for about fifteen minutes,”

The hospital was on the side of the jail which received the first rays of sunlight. Every morning for several weeks Burt stood there, posed at such an angle that when the sun peered over the east wall the first thing it saw was Burt’s backside. Hot water and sunshine almost but not quite cured him.

I can say, with pardonable professional pride, that the final touch was my idea. In our meager medicine chest was a tube of ointment labeled Gentian Violet. What it was for I didn’t know but experimenting on my own skin had shown that it was a mildly astringent indelible dye. Once applied it had to wear off. One morning after his sunbath I painted Burt’s bottom gentian violet. The effect was startling especially when, due to some chemical cause un-known to me, Burt’s bottom turned from gentian violet to a certain shade of vermilion I had seen many times before in the zoo at home on the bare posterior of a Hamadryas baboon.

Needless to say, many other sufferers from Palembang Bottom were following the experiment on Burt with an interest approaching the breathless. No class of medical students ever assembled with more eagerness in their lecture amphitheater to watch a professor stage a demonstration than gathered each morning outside the hospital of Palembang Jail to study the ups and downs of Burt’s case as he progressed from bucket to sunbath to painting.

As I delicately traced gentian violet lines on Burt’s anatomy I reflected, sadly, that probably this was the nearest I would ever come to knowing the inner thrill an artist feels while students follow his brush strokes. The greatest thrill, of course, came the morning Doc pronounced Burt cured. Cheering spectators shook Burt’s hand and the beaming patient said, “Now I can fearlessly face my wife.”

Language lessons, private and en masse, began in the first days of internment. Classes were conducted in Dutch, English, Malay, Spanish, French, German, Japanese and Russian. Languages were only part of our scholastic curriculum. Fully half of the prisoners were technicians of various kinds. They organized the Palembang Jail Engineering Association and held weekly symposiums on technical subjects, and smaller, twice weekly classes in various branches of engineering.

New Zealander Burt was the most dogged student in jail. He put in five hours a day for a year on Spanish and when he had reached a certain stage of proficiency reduced the Spanish studies to one hour daily and took up lessons on a jail-made guitar, strumming four hours a day for another year. He did it all to surprise his wife, explaining,

“She won’t believe it’s me when I walk in singing Spanish and strumming a guitar.”

Part 4

…. I dropped into the cell of New Zealand Burt to ask if he would give the next public lecture which Camp News sponsored weekly. Burt once had been a member of a British expedition to the Arctic.

“I think the boys would enjoy hearing some more about your experiences with Polar Bears,” I said.

Burt agreed they would. His previous lecture had only scratched the surface of anecdotes about the adventure.

As we discussed it I looked around Burt’s cell. Designed originally for one native prisoner, it was a little over five feet wide and nearly filled by the cement sleeping bench. Three men slept on the platform and Burt slept on the floor in the narrow space between the end of the bench and the door. Their bedding consisted of a rice sack apiece. Between their bodies and the concrete was one woven grass mat. There were no shelves or hooks on the bare walls, so their eating utensils and other belongings lay beside them on the bench or floor. The odor from an open drain a few feet outside the door filled the cell.

“You can almost cut it with a knife, can’t you?” Burt remarked sniffing.

He waved a wad of papers.

“I found these in the trash can outside the guardroom,” he said. “They’re old prison records.”

They looked as though they had been tom from a ledger. The pages were ruled in vertical columns and horizontal lines, with names of prisoners, their dates of admission and other data filled in.

“I’m going to use the unwritten spaces to keep a diary,” Burt said. “I just wrote a note in it to the wife telling her it’s the little things I miss most, things like shaving gear and handkerchiefs and a comb and needle and thread.

“I told her that confinement under these circumstances is making men irritable and we’re all losing our tempers over trifles.”

A cockroach appeared from under the bench, waved exploratory antennae and started sidling along where floor joined wall. Burt whipped off his terompak [Malay ‘terompah’ = wooden clog], struck at the cockroach but missed. The insect buzzed its undeveloped wings and sailed across the room. Burt made another pass and it scuttled for the dark opening under the bench.

Angered at his second miss Burt made a third vicious swing and lost his grip on the terompak which clattered out of sight under a bench. It must have hit a rat hiding in there for the startled rodent popped out of the black recess, leaped across the floor at our feet, shot out the door, cleared the walk in another jump and disappeared into the drain.

“What do you think of that?” Burt asked. “I’ll bet the Japs had that rat wired. My wife would never believe it. Flying cockroaches and fifth column rats.”

I left Burt and continued my rounds, exchanging gossip here and there and feeling around for the source of the latest fantastic rumor that Americans had landed on Bali.

Part 5

January 29th died New Zealander Burt, who had been the guinea pig for our Palembang Bottom experiments. Physically, he had been one of the toughest internees. He had studied Spanish and learned to play the guitar so he could surprise his wife when he got home.

Just before fleeing Singapore he had been notified of his decoration with the Order of the British Empire for his services with the engineering corps.

“They’ll probably send it to my wife to keep for me,” he said. “Boy, won’t that be a great day when I get home!”