This website documents what happened to a group of civilian internees captured and held by the Japanese starting in February – March 1942 and ending in November 1945. The text on this page and on many of the other pages on this website are based on the work of Judy Balcombe.

The Muntok Peace Museum follows the three principles of the Netherlands War Graves Foundation :– to remember the history, to support war victims’ families emotionally, and to educate people about wars in order to strive for Peace.

We hold in our minds forever all who have suffered during war, those who died, those who returned scarred by warfare, those who waited anxiously at home, those who mourned, those communities that suffered loss.

We remember those who acted with kindly compassion, those who bravely risked their lives for their comrades, and those who in the aftermath of war worked tirelessly for a more peaceful world.

We think of all those who suffer in wars today and recognize the great importance of building bridges between people, communities and countries and working for Peace in our struggling world. We thank you for visiting this website.

In June 2025 a blue plaque commemorating Margaret Dryburgh, was dedicated. A page about Margaret with details on the plaque ceremony can be viewed HERE.

We recognize that many of the prisoners held in the Sumatra camps were Dutch and their suffering was as great as that of the British, Australian, and other Commonwealth citizens.

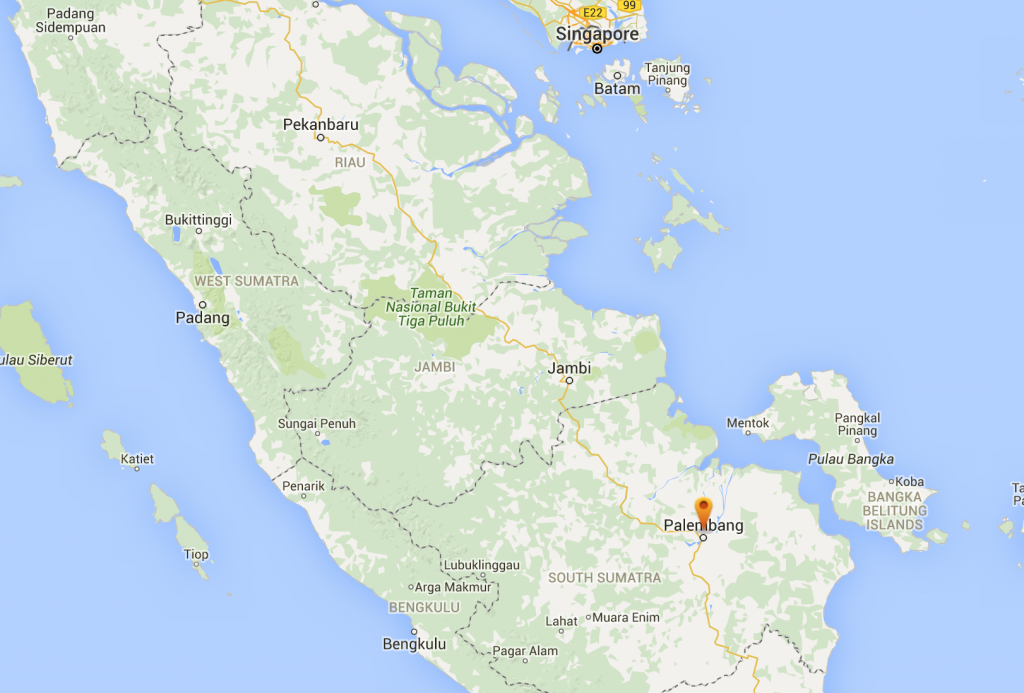

However, the focus of this website is on those who were living in Malaya and Singapore before February 1942 and who were imprisoned in Muntok, Palembang, and Belalau camps with Australian army nurses from the ss Vyner Brooke and British nurses.

Unlike the Dutch, whose military and civilian graves were moved to war cemeteries in Java, the graves of most allied civilians who died in Muntok, Bangka Island, were left behind after the war and were built over.

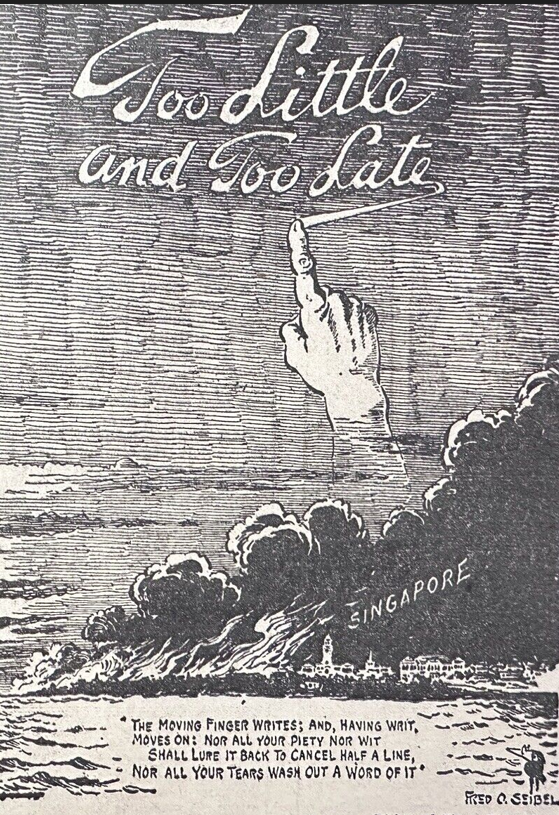

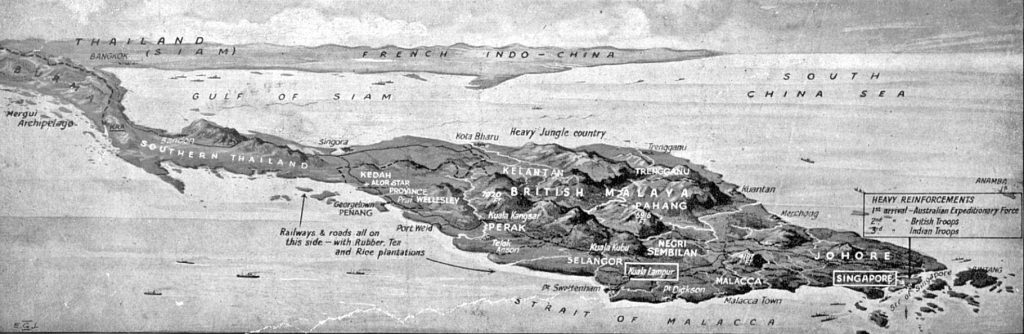

Our story begins when the Japanese army invaded Malaya on December 8th 1941. It was a well planned and coordinated assault on the world. On that day, as the hours passed, Pearl Harbour in Hawaii, Manila, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaya were bombed and the ‘Pacific’ War’ began. It was to last for nearly 4 years; hundreds of thousands died or were taken prisoner and for the survivors, life was altered forever.

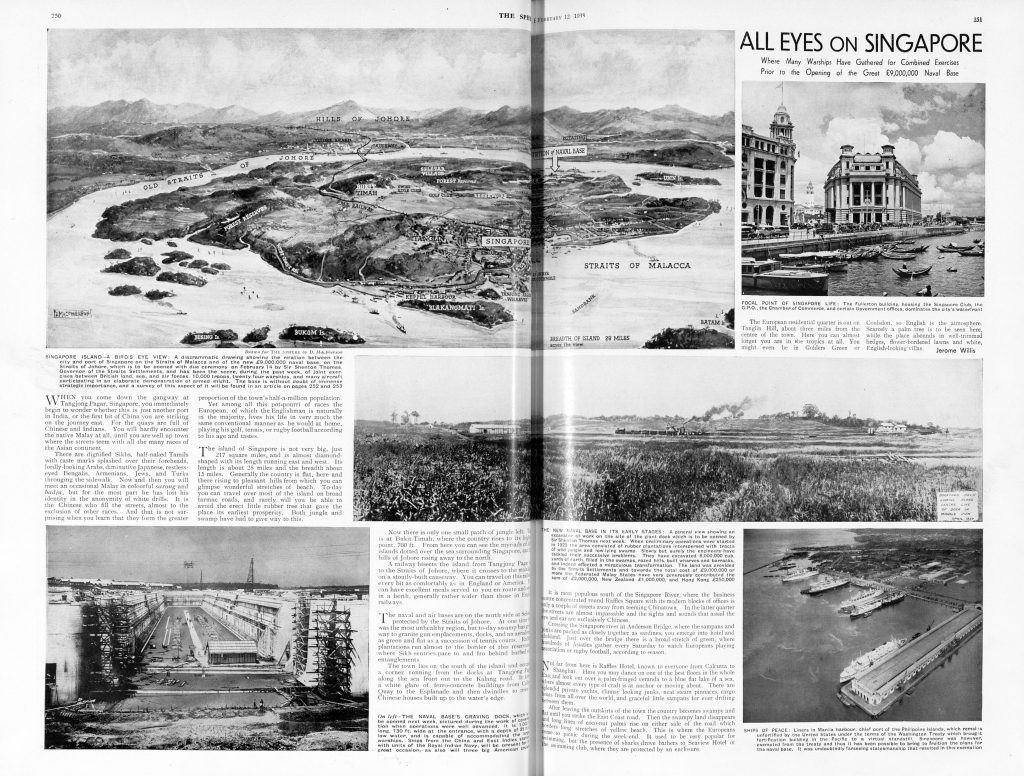

At first the British and Malayan governments told the inhabitants of Singapore and Malaya that there was nothing to fear. They said the countries were well-guarded by the British and Australian armies and by the strong forces of the Malayan and Singapore Volunteers.

The Japanese, they said, were small, ill-equipped, wore glasses and were ‘nearly blind.’ It was believed that Japanese tanks could never maneuver through the narrow Malayan roads.

But the Japanese, although bespectacled, were determined. Loyal to their Emperor God, they were unstoppable. They rode down the Malay Peninsula on bicycles; their tanks rolled on through the rows upon rows of rubber trees. Battles were bravely fought but the Japanese could not be repelled.

The Japanese military proved to be highly adept at outmaneuvering the British and Australians. They used tactics that included outflanking British and Australian positions by moving through what the British considered to be impassable jungle terrain, and they also used small boats to conduct amphibious landings and bypass British defenses that were concentrated along the main roads.

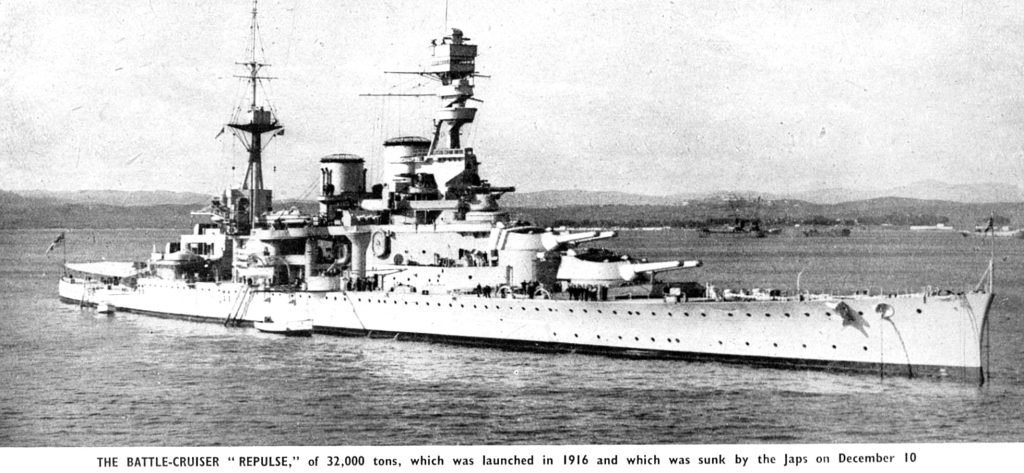

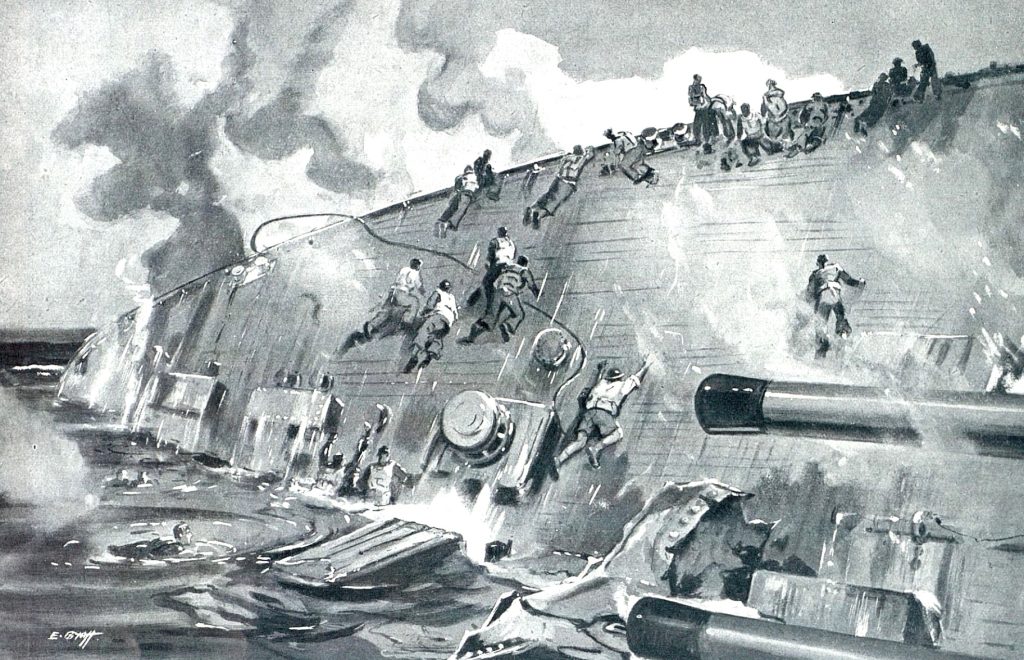

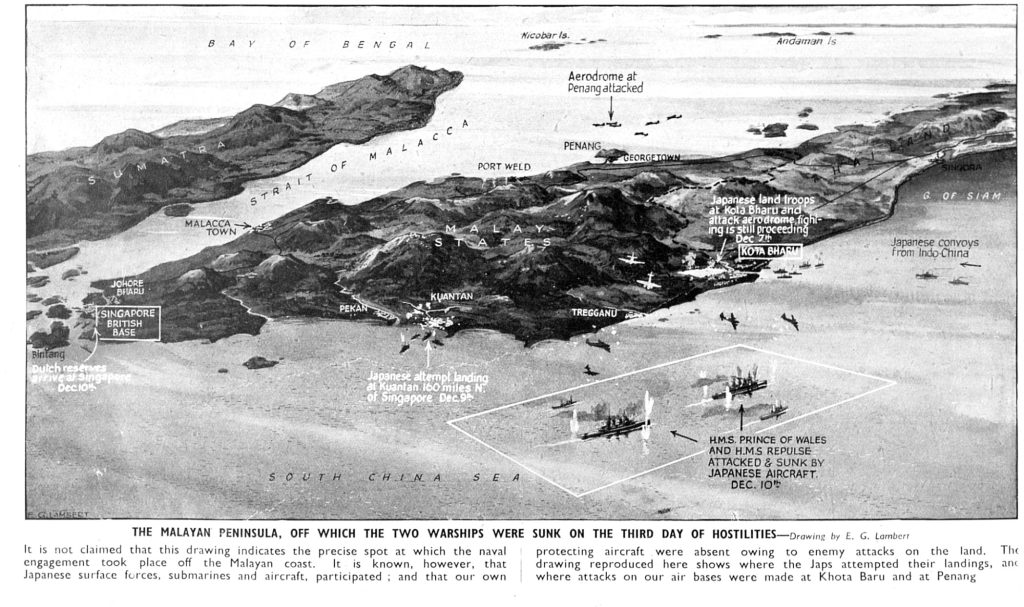

On Wednesday December 10, within three days of the opening of hostilities with Japan, the British Navy suffered a grievous loss with the sinking of the battleship Prince of Wales [35,000 tons] and the battle cruiser Repulse [32,000 tons].

The Japanese fleet had been watching the movements of the British naval forces and it was a Japanese submarine that first spotted the two large battleships. Immediately the submarine alerted the Japanese air arm and the planes launched an attack.

The Repulse was bombed and sank immediately with a great explosion. The Prince of Wales was hit and with a list to port attempted to reach safety but she finally sank, again with a great explosion.

Of the 2,700 crew members from both ships some 2,300 survived many of whom, without a ship, eventually joined the civilians who fled Singapore in the last few days before it fell.

When Churchill announced the sinking in the House of Commons he said that the ships were without their expected protection from the air. On Singapore the news of the sinking was a terrible blow to morale.

Families became fearful. European women were encouraged to take their children and leave, sailing for Australia, Ceylon, South Africa, or England. Some, however, believed Churchill’s advice that Singapore could not fall and chose to remain.

Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205195083

Men under 50 living in Singapore and Malaya were required to continue in their jobs, providing tin and rubber for the European War and maintaining infrastructure. They were required to join the fighting forces of the Malayan and Singapore Volunteers. They were not permitted to leave Singapore or Malaya without a permit. [This process took time and is described in Jock Brodie’s recollections which can be read here] .

After only some seventy days since the Japanese had landed at Kota Baru in Northern Malaya, they had fought their way down the Malay Peninsula and attacked Singapore on 8 February 1942. Women and children, earlier reluctant to leave, were now clamoring to board the flotilla of vessels commandeered to take them away.

Elderly men, government personnel, sailors from the bombed and sunk British warships, The Repulse and Prince of Wales and other soldiers en route to fight in Batavia also assembled on the docks to embark.

Passengers were hurriedly processed and transported in lighters out to their boats waiting in the harbour. There were tearful and frantic farewells by families as many men remained on shore. [A list of some of these ships and what happened to them and their passengers can be read here]

Many of the civilian men pushed their motor cars off the edge of the wharf, watching them sink slowly into the sea. Thus submerged, the cars could not be used by the invaders and might also prevent larger Japanese ships from docking at the harbour.

One of the ships that was allocated to take civilians and leave Singapore was the Giang Bee. Passengers rushed to board from the launches, hauling their meagre possessions up swaying ladders. Families’ suitcases fell open, strewing clothes onto the ground – there was no time to retrieve possessions.

The air was thick with acrid smoke from burning oil refineries and storehouses, both bombed by the Japanese and set alight by the British and Australian armies so the contents could not be used. Even in the dark of night, the sky was bright as day, with burning oil flames climbing up to 600 feet high.

Gordon Reis who was on the Giang Bee later wrote in his diary: ‘Never in my life shall I forget the dreadful carnage and the awful sight and impression of fire throughout [the city]. The town looked lit up and buildings were very obviously recognisable through the flames at night.’

Of the 100 or so vessels which left Singapore between 11 -14 February, 1942, carrying evacuees, only about 20 made it to safety. Even after the capitulation of Singapore on 16 February, vessels were still managing to leave the island, possibly raising the total to between 140 to 150.

The vessels included: tug boats, praus, sampans, junks, etc. Most of the casualties resulted from Japanese aerial bombardment and strafing and shelling from naval vessels which was inflicted on the motley flotilla of vessels as it sailed down the Bangka Straits towards Java. Accurate shipping departure and passenger records were not kept in the chaos of boarding and no one knows with certainty how many passengers there were, but it is thought that between 4 to 5 thousand people lost their lives on the eighty or so ships that were bombed and sank or captured.

The British military decoding apparatus had been dismantled and thrown into Singapore harbour so the Japanese would not know that earlier messages had been intercepted. Because of this, it was not possible for allied officials still in Singapore to receive the information that Japanese squadrons were flying in their hundreds over the shipping channel towards Palembang in Sumatra – exactly over the path of the evacuating boats. Enemy warships were undetected in the waters of the Bangka Straits.

The Giang Bee left Singapore in a convoy with two other boats, the Vyner Brooke and the Mata Hari. Passengers worked shifts in the engine rooms, shovelling coal into the red-hot furnaces, trying to drive the ships’ engines to their limits. Many of the civilians, some quite elderly, volunteered to help stoke the ship engine’s furnaces.

The boats left Singapore harbour, hoping not to be bombed or encounter sunken mines. The vessels surged through the ocean, trying to travel in the cover of night and hiding under overhanging trees on small islands during the day. Despite these efforts, the tell-tale hum of small planes with wings bearing the red circle of the enemy Japanese were heard and then seen overhead. Bombs fell, killing several people and damaging the engine room of the Giang Bee.

At night, Japanese warships approached. Captain Lancaster of the Giang Bee ordered a white flag to be raised and all women and children to stand exposed on deck, so the Japanese could see that civilians were on board. Spotlights illuminated the Giang Bee and Japanese loud-hailers ordered the ship to be abandoned.

Women and children entered the lifeboats, but two of the four boats had been riddled with bullet holes and their ropes shattered; this damage was not seen in the dark. The lifeboats boats collapsed into the sea, filling with water and sinking, killing those on board.

The warships next signalled their intention to sink the Giang Bee and fired shells into the stern. The many helpless passengers still on deck jumped into the water to their deaths or perished as the boat burnt and sank.

The Japanese warships then turned and departed, leaving hundreds of men, women and children still in the dark water, dead and drowning.

For two long days and nights, survivors from the Giang Bee struggled against the strong tides, striving for the winking lighthouse of Muntok on Bangka Island. Only 70 people managed to reach the shore, either in the two remaining lifeboats, drifting in lifejackets, or holding on to flotsam from the sunken boat. 223 people were missing, presumed dead.

The Mata Hari was relatively unscathed. A description of what happened to the Mata Hari based on notes kept by Arthur Henry Hogge and transcribed his son Philip can be found HERE.

The Vyner Brooke, the second vessel in the convoy, carrying passengers and Australian nurses, was also bombed and sunk by Japanese planes, despite displaying the Red Cross of a hospital ship. It is thought that 135 of her passengers and crew perished. Those who were able to reach the shore met with many different fates …

Parched, sunburnt, and exhausted, some people reached land, but not safety. There, many years of unbelievable hardship had just begun and it is these years that this website is dedicated to describing.

Once ashore, the civilians were eventually separated from the military and the two groups placed in different camps. This website, for the sake of brevity, follows only the fate of the civilians, not the military.

The Japanese officer in command of the civilian camps was Captain Seki Kazuo.

[The above is mostly based on Judy Balcombe’s description of her grandfather’s escape on the Giang Bee (Colin Campbell) ]

Not all those who ended up as civilian internees in the camps at Palembang and Muntok became so via their escape from Singapore. One group was captured on the Eastern side of Sumatra having been bombed out of their boat (Poleau Bras) and many Dutch were already resident in Sumatra and Java when they were interned.

[If there are any others out there who would like to share any Muntok – Palembang – Belalau recollections during 1942 – 1945, we would be happy to post them on this site. Please use the contact form that can be found on the left. Thank you!]