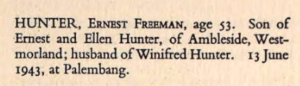

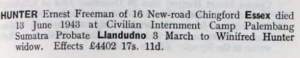

Ernest Freeman Hunter was born in 1891 at Ambleside, Westmorland. He was a WW1 Signals Corps veteran. Cable & Wireless Engineer. His wife Winifred was evacuated. He died in captivity 13.6.43 aged 53 at Palembang, probably of an aneurism.

Reis noted in his diary: ‘On 13/6/43 Hunter of Cable and Wireless died from heart?’

William McDougall gives a fairly detailed description of Hunter’s death in his diary (published as ‘If I Come Out Alive’) pp. 193-195. The entry is dated 13 June 1943:

Father Elling wakened me at 4:45am, as usual. As I hurried thru the dark ward noticed ‘matron’ Kendall fussing with E. F. Hunter, 52, Cable & Wireless Limited. Several others also there. “He’s been making funny noises and now we can’t wake him up,” said Kendall, shaking him again: “Hunter”.

I felt Hunter’s leg, shook it once, called him, determined there was no sign of pulse – it felt dead to me – & hurried off to rouse Dr. West. I was sure Hunter was dead. He was. West jumped from his top bunk, over Harrison in their room, at my summons, snatched his flashlight & we hurried back. I told West “I think he’s dead.” Raising the small mosquito net which covered Hunter’s upper torso & head, West flashed the light in Hunter’s white face. Half opened, blank eyes & open mouth – that “dead look” so familiar to those who have seen it.

“He looks dead, alright,” said West & confirmed his words with his stethoscope. Probably an aneurism. Last night Hunter complained to Doc of pain high in the chest and running down the arms. West thought it muscular.

We picked him off the bed, laid him in stretcher and carried him into the surgery, where West examined him further, & as I sat him up so West could look at his back & be sure he had died lying down & not fallen, one of his [dental] plates fell out. I picked it up and West removed the other dental plate. Harley Clarke is going to boil them up & use them for needy patients here.

The episode began and ended in 15 minutes or so. I arrived at the first Mass just before Communion, shortly after 5, before dawn had begun to lighten the darkness. The double row of mosquito nets seemed scarcely disturbed, but many patients must have been wakened by the stir and especially shocked must have [been] Fraser, a tall, gaunt Briton sleeping next to Hunter. For Fraser is living on borrowed time. He is one of those men, rare in medical annals, who survived a coronary thrombosis, caused by an embolism. Five years ago he was stricken. In this camp he has seen 4 men die of heart attacks, & this morning one of them in the bed next to him.

Ernest Freeman Hunter was a white-haired, pale skinned pleasant man of 52, possessed of a dry wit. We used to rag each other over his spots which I used to treat for a long time. He was back form Charitas [hospital] only a few weeks after a hernia operation. Hunter spent all of World War One in France, mostly at the front, in the signal corps. He went unscathed through that war and saw much of this one, having evacuated [from] Greece then Crete & finally Singapore & always among the last to leave. He was long on the traffic side of Cable & Wireless & knew many journalists. I regret that I let all this time go by without really talking to him concerning his experiences.

Just before roll call Hunter’s corpse was laid in the committee block. At 11.00 am Rev. Wardle conducted a short memorial service. The plank coffin resting on the bunk shelf. At 4:00pm an open truck pulled up, the same one that brings our rations. Six barefooted Malay coolies, wearing black trousers, coats and songkas [caps] ….. After a last inspection by Javanese officer to confirm it was [the] same corpse, coffin was nailed shut, & six camp members bore it on their shoulders to the truck. Wardle, V. F Fermaugh, Banks, Penrice & Tisham rode on the open truck with the coffin & Coolies. He was buried in the cemetery behind Charitas Hospital where other British & Dutch internees & military lie.

When the coffin was being carried out, Japanese & Malay guards bowed their heads & stood at attention. But a certain Briton kept working in his garden plot near the fence, paying no attention, & his disrespect incensed the J.[apanese] guard, who threw rocks at him, but did not shout, as all else was silence.

Right now I think I will remember for a long time Hunter’s face when doc raised the mosquito net & shone his flashlight rays on it. The white face of death doubly pale in its natural whiteness, the slack mouth and jaws half-opened, blank eyes, the white hair – all nestled in the small space within the net.

When Hunter was in the morning surgery line while I treated him for various sores, I told him that once I got him in the hospital his goose was cooked, because he would go out only in a wooden overcoat – Words spoken in jest!

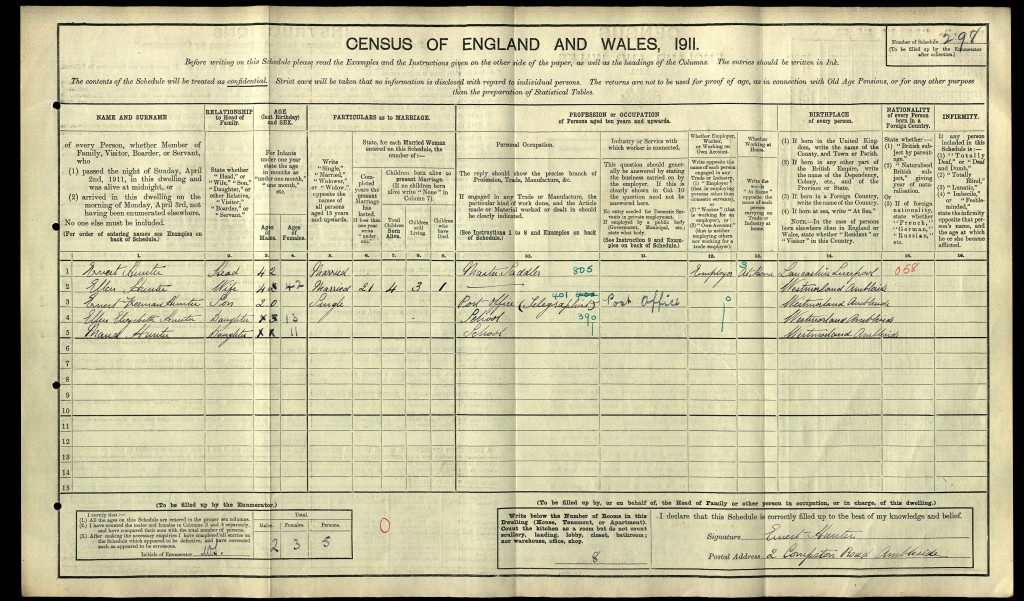

Ernest Hunter appeared on the 1911 census aged 20 residing at Ambleside in Westmorland. He is a ‘telegraphist’ working in the post office and his father is a ‘Master Sadler’: