One of the families most affected by the Palembang – Muntok – Belalau experience was the Boswell family, if for no other reason than the number of family members who were involved.

Leonora Josephine (‘Nora’) and Frederick (‘Fred’) Boswell were married in 1925. Prior to that marriage, Nora had been married to Frank de Mornay and from these two marriages Nora had a total of thirteen children, eleven of whom carried the Boswell family name.

These eleven children of Nora’s, her two daughters-in-law, her granddaughter and Nora and Fred were evacuated from Singapore on the 12th February 1942 and sailed away toward the Banka Straits. Fred was on board the Mata Hari while Nora and the rest of the family were on the Giang Bee. However, four of the children (listed below) were lost at sea as a result of the Japanese bombardment and sinking of the ship. The others managed to survive and found themselves captives of the Japanese.

From Nora’s first marriage to Frank de Mornay, the children who took the Boswell name and who were evacuated from Singapore were, in age order: 1. Albert (lost at sea); 2. Elder (survived) married to Charlotte (nee Marsh); 3. Norman (survived), married to Clare (nee Marsh); 4. Noel (lost at sea); 5. Malcolm (survived); and 6. Clive (lost at sea).

The children from Nora’s marriage to Fred Boswell (in age order) were: 1. Drina (survived); 2. Corrine (lost at sea); 3. Kenny (survived); 4. Joan (survived); and 5. Maisie (survived).

The individual histories of most of the Boswells who were interned in Sumatra are recorded here followed by Drina Boswell’s recollections of the war.

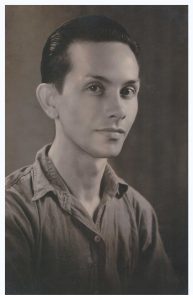

Frederick (“Fred”) Boswell

Fred was born on the 31st August 1892 in Province Wellesley to Richard Victor and Maria Josephine Boswell. He was the middle child of three boys; his youngest brother died aged only two. He also had three half-sisters and five half-brothers from his father’s first marriage.

The Boswells were a colonial family. Fred’s father was Assistant Superintendant / Superintendant of the Public Works Department, a job that took him and his family to Malacca, Penang and Singapore. The family settled in Singapore during Fred’s school years and he and Herbert, his brother, attended The Raffles Institution.

Like most of the Boswell males, Fred was a keen sportsman. He was also a member of the D (Eurasian) Company of the Singapore Volunteer Corps at its inception in 1918.

In 1925 he married Leonora Josephine de Mornay (nee de Souza) and they had five children: Drina, Corrine, Kenny, Joan and Maisie. Children from Nora’s first marriage also joined the household. Initially the family lived in Singapore but moved to Kuala Lumpur circa 1928 because of Fred’s work.

Fred had worked for Robinsons Department Store in both Singapore and Kuala Lumpur but by the time of the Japanese invasion of Malaya in 1941 he was working for the Wilkinson Process Rubber Company Ltd at Batu Caves. He stayed on in post following the Government’s directive for men to remain in their jobs. When it became clear that the threat from the approaching Japanese army was growing ever closer, Fred and his family fled to Singapore, his last task being to burn the factory so that the Japanese couldn’t take possession of the valuable stocks of rubber.

At the docks on 12th February 1942, Fred became separated from the family and was pushed onto a launch which headed to the Mata Hari while the launch carrying the rest of the family went to the Giang Bee; the two ships met very different fates.

The surviving members of the family met up briefly in Muntok a few days later but then the women and men were separated and went to their individual camps. That was the last time Fred saw Nora and his daughters.

Like many people whose history is recorded on this site, Fred was moved to a number of different camps: Muntok Jail, three camps in Palembang and then Muntok Jail again. At the Palembang Jail camp, William McDougall’s “Camp News” from the autumn of 1942 records Fred, along with his stepsons, taking part in a camp concert – one of the pleasanter interludes of early camp life when spirits were still relatively high and disease and malnutrition hadn’t yet taken their toll.

Sadly, almost two and a half years of a harsh existence and near-starvation rations eventually did take their toll, and on the 11th July 1944 at Muntok, Fred died of Beriberi. He was 51 years old. His grave is E1 on the Graves page.

Leonora Josephine (‘Nora’) Boswell

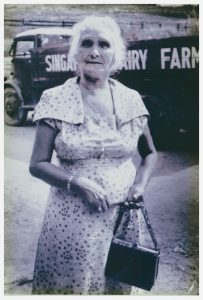

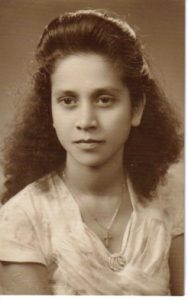

Nora was born in Singapore on the 2nd April 1889 to Clothilde and Joseph Louis de Souza and was the eldest of a family of three girls: Nora, Bertha and Rose.

Nora was married twice – first to Frank de Mornay and later to Frederick (‘Fred’) Boswell. Nora and Fred lived in Singapore initially but after a few years, because of Fred’s work, they moved to Kuala Lumpur with their children and most of the children from Nora’s first marriage. They were living in KL at the outbreak of war in the Far East.

At the beginning of January 1942 Nora, Fred and their family fled from their home in Kuala Lumpur to Singapore to escape the advancing Japanese Army and in the hope of being able to get a ship to take them from Singapore. They had to wait several days before they could get on a boat during which time conditions in Singapore grew ever more desperate.

On the 12th February they finally managed to secure places on almost the last of the boats to leave Singapore. Fred was bundled on to the Mata Hari while Nora and all the family boarded the Giang Bee; all the boats were severely overcrowded. The following day the Giang Bee was bombed. When the time came to abandon ship, Nora and all of the family except her sons Albert, Noel and Clive and her daughter Corrine managed to get into the same lifeboat. Nora prayed that they would find places in the second lifeboat, the only other one to leave the Giang Bee. But when she arrived at Muntok she discovered that these four children were missing as was Nora’s sister, Rose. Soon after they arrived in Muntok, Nora was parted from Fred and her three eldest sons as the men and older boys went to one camp and women, girls and children to another. It was to be the last time she ever saw Fred.

Nora spent the next three and a half years in various camps in Sumatra. Nora was a splendid cook. When they were first interned she was a permanent member of the kitchen squad – not that her culinary skills could be put to good use with the very limited rations available. Conditions worsened as the war went on and food rations dwindled to a very small portion of rice daily. She became very ill and unable to work and remained unwell for the rest of her time in camp – the doctors thought that if her internment had lasted another week she would not have survived. When the Japanese announced that the war had ended, the men were able to come from their nearby camp and visit the women. Only then did Nora learn from her remaining four sons that Fred had died in July 1944.

After their liberation, Nora and her family returned to Singapore – she had no wish to live anywhere else as she always believed that if her four missing children had survived the bombing of the Giang Bee, that it would be to Singapore that they would come to look for her. The family made many enquiries of the Red Cross and other organizations after the war, trying to find the missing family members or find out what happened to them, but to no avail. They had to accept that they had not survived the shipwreck in the Banka Straits but Nora would never say they were dead: she always referred to them as “my missing ones”.

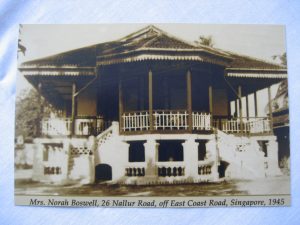

Initially Nora stayed in the Sime Road Transit Camp in Singapore. Later she moved to a large house close to the East Coast Road which was home to various family members and friends over the years and the scene of many large family gatherings and celebrations. The house and garden were a wonderful place for the children in the family to play. She lived there with her son Malcolm for many years, matriarch to the large Boswell ‘clan’ and indulgent grandmother to her many grandchildren.

For the rest of her life Nora lived with the memories and sorrows of what the war did to her family. She died in Singapore on the 22nd July 1966, aged 77.

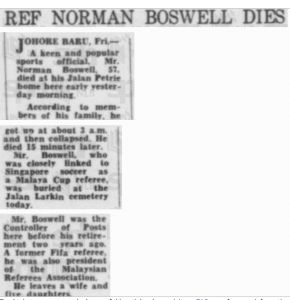

Norman Boswell

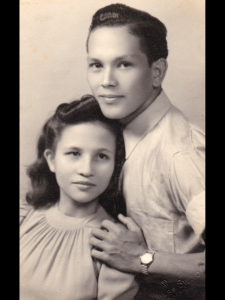

Norman was born on 2nd April 1919 in Singapore, the son of Frank de Mornay and Lenora (Nora) Josephine (nee de Souza). In 1925 Nora was married to Frederick Boswell and Norman’s surname was changed to Boswell.

When the Japanese invaded Singapore, Norman was already married to Clare Marsh (born on 26th August 1923) and they had a daughter Felice Anne who was born on 27th September 1941

Because Norman and Clare never spoke of their time in the camps we are unable to state what they experienced although we can assume they shared the same physical privations and poor health like most of the others.

After surviving the camps, Norman died on 20th May 1976 in Johore Bahru, Malaysia. Clare is still living, a frail lady, who will be 93 years old in August 2016. Clare has said that she has forgiven the Japanese.

At the end of this page is a note from Valarie Wood, the daughter of Norman and Clare Boswell, on the celebration of her mother’s 90th birthday party.

Malcolm Boswell

Malcolm was the second youngest child from Nora’s first marriage. He was born in Singapore in December 1922 and was brought up by Nora and her second husband, Fred. Although christened de Mornay, he took his stepfather’s name and was always known as Malcolm Boswell.

The family moved to Kuala Lumpur when Malcolm was about six years old. Along with his brothers, he attended the St John’s Institute in KL. He left KL with the rest of his family in January 1942 and went to Singapore from where he left on the Giang Bee on the 12th February. When the ship was bombed on the following day, Malcolm sustained a shrapnel wound to his back which troubled him for the rest of his life.

Along with his stepfather and his brothers, he was interned in six camps over the next three and a half years. Malcolm had a good singing voice which made him popular at the camp concerts in Palembang.

After the war Malcolm returned with the remaining members of his family to Singapore. Initially he worked for the RAF in a clerical capacity but later started working at the Singapore Recreation Club (SRC) in a clerical and receptionist role. He remained in the employment of the SRC for the rest of his working life.

He never married and lived with his mother and other family members for many years. Malcolm was artistic, creative and a man of great faith. He had a kind and happy disposition which made him a popular uncle to his many nieces and nephews.

Malcolm never left Singapore/Malaya after the war other than for one trip to Perth in Australia in 1996 for a reunion with sisters Drina, Joan and Maisie and other members of his family who had made their home in Australia.

He died in Singapore at the age of 80 in May 2003.

Drina Boswell

Drina was the eldest of Nora and Fred’s five children and was born in Singapore in 1925. Her father’s job necessitated a move to Kuala Lumpur when she was about three years old, and it was in KL that she spent most of her early life.

Along with her three sisters, Drina had attended the Convent of The Holy Infant Jesus in Kuala Lumpur. She loved school and was a keen student. Outside of school Drina helped her mother around the house and to cook meals for the large Boswell family – a role that earned her the fond name of “little mother” from her older brothers. She learned to become an excellent cook from about the age of ten just by watching her mother cook.

Drina was 16 when the family hurriedly left KL for Singapore and the hope of getting on a boat that would take them to safety. She and the majority of her family left Singapore on the Giang Bee, but sadly not to safety. Following the ordeal of the ship being bombed and spending two nights in a lifeboat, Drina and some of her family arrived at Muntok and so began three and a half years of internment and of being moved from camp to camp. Her mother became very ill during internment and it fell to Drina to look after her and the rest of the family. In the camps she helped cut down trees, chop wood for the fires used for cooking, and dug latrines. And worse duties were to follow as the months passed and fellow internees died.

Her cooking skills helped her in the early days in camp when those camp members who still had money, paid her to cook for them and she was able to use the money to buy extra food for her family. She had a sweet singing voice, and in those same early months before the effects of malnutrition and illness were evident, Des Woodford (who was initially in the women’s camps) recalls Drina singing – something her children remember her doing in later life as she went about her work.

Drina and her family returned to Singapore after they were liberated. After a period in hospital recovering from malaria and undergoing a careful re-feeding programme because of her malnourished state, she joined the family at Raffles Hotel before they moved to Sime Road Transit Camp. A little later she got a job as a telephonist working for RATWE – the Dutch Repatriation organisation.

Drina and her family returned to Singapore after they were liberated. After a period in hospital recovering from malaria and undergoing a careful re-feeding programme because of her malnourished state, she joined the family at Raffles Hotel before they moved to Sime Road Transit Camp. A little later she got a job as a telephonist working for RATWE – the Dutch Repatriation organisation.

She met Tom Leeson, her future husband, while the family was staying at Raffles. Tom was a CQMS in the Royal Signals and had been in Burma under Lord Mountbatten’s command and entered Singapore as a member of the liberation forces. Tom had been ‘called up’ in 1942 and when his war service came to an end he re-enlisted. His posting to Singapore was extended so Drina was able to start her married life close to her mother and the rest of her family. However, in 1952 Drina, Tom and their young family left Singapore for England, the place of Tom’s next posting, and a very different life to the one she’d left behind. Food rationing awaited her in England – ironic to have to face a shortage of food again as food had become more plentiful in Singapore – and a few months later she had her first experience of a bitter English winter and snow. For the next 26 years Drina (and hers and Tom’s six children – until they reached adulthood) accompanied Tom on his various postings. One of these was in Singapore during 1961-1964 which gave her a much longed-for chance to spend time with her mother and the rest of her family once more.

When Tom retired from the army they settled in Sussex and Drina spent the rest of her life in Shoreham, still effortlessly creating meals that were a hit with everyone fortunate enough to sample them, and taking pleasure and pride in what she called her “blessings”: her children, six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

In 2005, Drina and her friend Doris Hewiit, who was in camp with her, were interviewed for BBC ‘Breakfast’ as part of the BBC’s programmes marking the 60th anniversary of the ending of war in the Far East. In the interview she recalled aspects of camp life and stated that while she could never forget what she had undergone she was able to forgive those who had caused the hardship and suffering she had endured.

Drina died at home on the 3rd April 2008, aged 82.

Kenneth (Kenny) Boswell

Kenny was named Kenneth Louis Mountbatten Boswell. He was born in Kuala Lumpur on 31 March 1929. Kenny was the third of five children born to Nora and Fred. Kenny loved being part of a large family and got on well with his sisters and stepbrothers.

Kenny was educated with his stepbrothers at St John’s Institute in KL. With the threat of the Japanese advance, Kenny’s parents made the decision to leave KL for Singapore with their family in January 1942. Kenny and his family departed Singapore on the Giang Bee on 12 February 1942. His father, Fred, became separated from the family and sailed on another ship, the Mata Hari. The Giang Bee was bombed the following day by the Japanese.

Kenny was educated with his stepbrothers at St John’s Institute in KL. With the threat of the Japanese advance, Kenny’s parents made the decision to leave KL for Singapore with their family in January 1942. Kenny and his family departed Singapore on the Giang Bee on 12 February 1942. His father, Fred, became separated from the family and sailed on another ship, the Mata Hari. The Giang Bee was bombed the following day by the Japanese.

Kenny was interned with his mother and his sisters in the women’s camp for a short while in Sumatra and was taken from them to join his father and older stepbrothers in the men’s camp. They were interned in six camps over the next 3½ years. He learnt to be resilient, as all his family did, in the hardship they experienced.

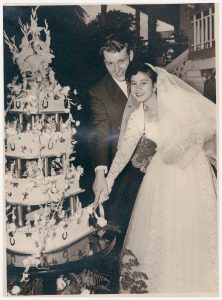

Kenny returned to Singapore after the war with the surviving members of his family. They were accommodated at Sime Road Transit Camp where he was introduced by his youngest sister, Maisie, to Brenda Morier when they were both sixteen. They married in October 1949 aged 20. They had a good marriage, and three children: Peter (1951), Paul (1953-1966) and Carolyn (1954). They lived with Nora in her home in Nallur Road after their marriage for five years before Kenny relocated with his young family to KL. Kenny was employed as a clerk of works, and later as a civil / construction engineer.

Kenny returned to Singapore after the war with the surviving members of his family. They were accommodated at Sime Road Transit Camp where he was introduced by his youngest sister, Maisie, to Brenda Morier when they were both sixteen. They married in October 1949 aged 20. They had a good marriage, and three children: Peter (1951), Paul (1953-1966) and Carolyn (1954). They lived with Nora in her home in Nallur Road after their marriage for five years before Kenny relocated with his young family to KL. Kenny was employed as a clerk of works, and later as a civil / construction engineer.

Kenny was a loving husband, father and son. His mother, Nora, sisters and stepbrothers in Singapore were always important to him and many trips were made to Singapore to spend happy times together. Kenny had great charm, he was attractive and generous, and had the ability to make people feel special.

Kenny had a second marriage to Jennifer Goh and two children, Sharon (1970?) and Daryl (1975?).

He was killed in a motor vehicle accident near Ipoh in October 1984. He was 55 years of age. Kenny is loved and remembered by his children, and all who knew him.

Joan Boswell

Joan Kathleen Matilda Boswell was born in Kuala Lumpur on the 2nd October 1930. Joan was the fourth of Fred and Nora’s five children.

Joan was an outgoing, vivacious girl. Like her sisters she attended the Convent of The Holy Infant Jesus in Kuala Lumpur and was near the end of her primary school education when the war with Japan forced her parents to decide that the family had to leave their home in KL and head for Singapore. They hoped that would offer them the chance of getting on a ship to take them away from the dangers of Singapore and Malaya.

Her experiences after leaving KL are told in the accounts of her parents and older siblings and in the recollections of her sister Drina, which are recounted at the end of the section on the individual family members’ details.

During internment, young as she was, Joan too was expected to undertake manual labour. She and Drina tried to earn a little money by doing various jobs in the camps for some of the Dutch internees. They used whatever money they earned to buy some food on the black market for their mother.

On returning to Singapore after the war, Joan had to resume her interrupted education. She attended the Katong Convent School in Singapore and finished her schooling after Standard 7. She had learned to type at school and when she left she worked as a clerk-typist for the RAF. It was while working for the RAF that she met Neil Weston, a young non-commissioned officer; she and Neil married in August 1955.

On returning to Singapore after the war, Joan had to resume her interrupted education. She attended the Katong Convent School in Singapore and finished her schooling after Standard 7. She had learned to type at school and when she left she worked as a clerk-typist for the RAF. It was while working for the RAF that she met Neil Weston, a young non-commissioned officer; she and Neil married in August 1955.

Whilst still in Singapore Joan gave birth to the first of her four children, Patrick Neil (1956). She followed her husband on postings first to Malta, where Michael was born (1958), then Gloucester where Simon Anthony was born (1960) and then to Hornchurch in Essex where her last child, Shaun Vincent, was born in 1962. The family moved to Salisbury (1966-67) and then Marlow (1968-69), following the usual RAF postings merry-go-round. But with four young children at hand, on their next move (this time back again to RAF Innsworth in Gloucester in 1969), Joan and Neil decided to purchase a home and settle down. In 1971, Neil was posted to RAF Patrington, but this was taken as an unaccompanied single posting rather than as a family posting and so Joan was left to cope with four young boys, with Neil returning home on a regular basis at weekends and other episodes of leave.

Whilst still in Singapore Joan gave birth to the first of her four children, Patrick Neil (1956). She followed her husband on postings first to Malta, where Michael was born (1958), then Gloucester where Simon Anthony was born (1960) and then to Hornchurch in Essex where her last child, Shaun Vincent, was born in 1962. The family moved to Salisbury (1966-67) and then Marlow (1968-69), following the usual RAF postings merry-go-round. But with four young children at hand, on their next move (this time back again to RAF Innsworth in Gloucester in 1969), Joan and Neil decided to purchase a home and settle down. In 1971, Neil was posted to RAF Patrington, but this was taken as an unaccompanied single posting rather than as a family posting and so Joan was left to cope with four young boys, with Neil returning home on a regular basis at weekends and other episodes of leave.

During this period, Joan’s two sisters, Drina and Maisie, were also in the UK and so the family was able to get together on a semi-regular basis and maybe this was Joan’s happiest period. She was vivacious, attractive and extrovert, extremely house proud, independent (driving the children to school, games and functions etc) and playing badminton regularly. Joan had the most angelic singing voice and frequently would sing children’s nursery rhymes, including a favourite, “Freddy had a Fine Ripe Cherry”. She took a part-time position as a telephone operator with the then equivalent of British Telecom and appeared happy, but regrettably the seeds of her past in the camps in Indonesia were to come back to haunt her.

Over the next few years she started to suffer flashbacks to her time in the camps and to hear the voices of her deceased brethren. In 1975/76 Joan was diagnosed as suffering with paranoid schizophrenia for which she required inpatient psychiatric treatment on a semi-recurrent basis over the next two years. Following her discharge she was a lifelong outpatient requiring medication and occupational therapy to keep her condition under control. Neil retired from the RAF at the rank of Squadron Leader to look after Joan and the family persevered, but Joan never recovered fully despite being able to lead an independent life for much of the time

Over the next few years she started to suffer flashbacks to her time in the camps and to hear the voices of her deceased brethren. In 1975/76 Joan was diagnosed as suffering with paranoid schizophrenia for which she required inpatient psychiatric treatment on a semi-recurrent basis over the next two years. Following her discharge she was a lifelong outpatient requiring medication and occupational therapy to keep her condition under control. Neil retired from the RAF at the rank of Squadron Leader to look after Joan and the family persevered, but Joan never recovered fully despite being able to lead an independent life for much of the time

After Neil’s death from cancer in 1999 at the age of 65, Joan was looked after by family and in community care until her death on 30th November 2007, aged 77, following a short illness.

Maisie Boswell

Maisie was born in Kuala Lumpur on the 24th November 1932 and was christened Maisie Mary Madge. She was the youngest of Fred’s and Nora’s five children and until she started school would accompany her parents on the journeys to and from Singapore that were necessary for her father’s work.

She started school at the age of seven, joining her sisters at the Convent of The Holy Infant Jesus in Kuala Lumpur (“Convent Bukit Nanas”). She recalls the daily journeys to school with her sisters: she would sit on her sister Drina’s lap in the rickshaw that took them all to school, and then there would be a long climb up several steps to reach the school building. Her education at the convent was short-lived and ended abruptly when the family had to leave Kuala Lumpur in haste because of the Japanese invasion of Malaya in 1941/2.

With the rest of her family she endured the trauma resulting from the evacuation from Singapore on the ‘Giang Bee’, the loss of four members of her family and the separation from her father at Muntok which was to prove final and, because she was so young, left Maisie with few memories of her father.

As the youngest, Maisie had always been very close to her mother. During internment she attended the ‘school’ run by the Dutch nuns but spent most of her time staying close to her mother’s side. The Boswell family enjoyed singing and Maisie was no exception. At one of the camps in Palembang she took part in a concert singing ‘Soldier, soldier, won’t you marry me?’ with a young boy called Percy Dunn. Also in the camp were Percy’s mother and his sister Maureen. Percy would crawl under the camp fence to get sweet potatoes and tapioca and throw them over the fence to Maisie and Maureen.

When the Boswell family returned to Singapore after their liberation in September 1945, Maisie went to the Katong Convent School with her sister Joan. She spent two years in Standard 5 but found both algebra and geometry difficult. Her mother could not afford to pay for private tuition for her so it was agreed that she could leave school at the age of 15 and hence her working life started at that young age. Maisie was blessed with a good, clear speaking voice as well as a good singing voice. Through one of her cousins she managed to obtain work as a telephonist at the police exchange, leaving after six months only because she was no longer able to get transport to and from work. She was given a good reference and applied for, and got, a job as a telephonist with ICI. She stayed with ICI for 18 years and was very well thought of: the Chairman used to call her “the voice of ICI”.

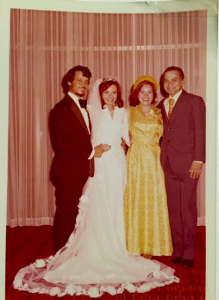

On December 26th 1951 she married Deryck Woodford. She had known Deryck for some years as he was a good friend of Maisie’s brother Kenny and would often come to the Boswell family home. They had their only child – a daughter whom they christened Maureen Margaret – at the end of October the following year. They started their married life living in her mother’s house until they were able to find a home of their own. Maisie was a devoted daughter and in later years was able to provide her mother with a home, as towards the end of her life, Nora came to live with Maisie, Deryck and Maureen until Nora’s death in 1966.

Maisie was a good homemaker as well as a very good cook, baking cakes being her speciality.

Deryck had been working as a stenographer with the RAF but when the RAF pulled out of Singapore he felt that life would be better for them all in England. In 1969 they moved to the UK and settled in Gloucester, close to Maisie’s sister Joan and to good family friends. Deryck worked as a clerical officer for the Land Registry in Gloucester. Maisie worked for a while as a telephonist on the main Gloucester exchange but also worked as a sales assistant for large department stores (Marks and Spencer, Kendalls and Debenhams).

In 1975 their daughter Maureen married Kieran O’Hara who she had met while on holiday in Singapore and they went to live in Perth in Australia. Maisie did not enjoy good health in England and was unhappy being apart from her only child, so in 1976 she and Deryck left England and went to live in Perth. It was a good move for many reasons. She had always enjoyed the company of others and loved dancing and socialising; as members of both Maisie’s and Deryck’s family were also living in Perth it meant that the same support and family gatherings that they had enjoyed in Singapore were once more part of their lives. They also had the pleasure of spending lots of time with their three granddaughters as they grew up.

In 1975 their daughter Maureen married Kieran O’Hara who she had met while on holiday in Singapore and they went to live in Perth in Australia. Maisie did not enjoy good health in England and was unhappy being apart from her only child, so in 1976 she and Deryck left England and went to live in Perth. It was a good move for many reasons. She had always enjoyed the company of others and loved dancing and socialising; as members of both Maisie’s and Deryck’s family were also living in Perth it meant that the same support and family gatherings that they had enjoyed in Singapore were once more part of their lives. They also had the pleasure of spending lots of time with their three granddaughters as they grew up.

Deryck died suddenly in 1988 of a ruptured aortic aneurysm. Maisie spent the next three and a half years on her own but in November 1991 she married Gerry Prendergast, a widower. The following year they travelled to England, Ireland (the place of Gerry’s birth) and America which allowed them to catch up with family on the other side of the world, and in 2002 Maisie made a return trip to the UK.

Maisie and Gerry continue to live in Perth enjoying time with their families – daughters, sons, granddaughters, grandson and great grandchildren. Maisie’s love of singing has never left her and she still sings in the choir of the church of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour in Castledare in Perth.

Drina’s recollections of the wartime

experiences of the Boswell Family

We were a large family. Her marriage to my father was my mother’s second marriage; they had five children. Additionally, six sons from my mother’s first marriage took my father’s name. The two older boys were married and one had a baby daughter.

My father, like many others at the time, never imagined that Churchill would risk Malaya and Singapore falling to the Japanese, as they were very important British possessions. Consequently no plans were made for us to leave, although the sinking of the battleships the Repulse and the Prince of Wales in December 1941 caused Daddy to lose heart as he acknowledged that the war in Europe was taking priority.

My family had befriended the British soldiers who were billeted on the racecourse, close to our house in Kuala Lumpur. It was these soldiers who told us that, contrary to the propaganda broadcast on the radio, the Japanese were advancing rapidly down the peninsula and the allied forces were unable to hold them back for much longer. They urged my father to leave for Singapore immediately. On the 6th January 1942 we fled to Singapore, taking with us what few possessions we could carry.

In Singapore we stayed with my aunt and her family while we waited for boats to take us away from the island. There were hundreds trying to leave and when word got out that a boat was going to depart – rumours abounded about departing boats – panic ensued as people tried to fight their way to the front of queues. Some tried to bribe others to give up their places in the queue and people dreamt up the most outrageous reasons as to why they should have priority, while others pulled rank. We spent the last two days and nights in Singapore sheltering in the basement of the Union Building in Clifford Square, opposite Clifford Pier, from where we would leave. There were rats in the basement. Many other people were with us in this basement and no doubt other buildings in the docks were being similarly used. Singapore was being bombed constantly, with the harbour area being targeted particularly, and we feared we would never leave.

On the 12th February 1942 we were told that three boats would be leaving Singapore and we were hurriedly pushed into launches to take us to the boats waiting outside the harbour. In the chaos and panic that ensued – bombs were again raining down on the docks and people were pushing and fighting to get into the launches – my father was separated from the rest of us. The launch he was on headed to the Mata Hari; the rest of the family were taken to the Giang Bee. The third boat to leave that day was the Vyner Brooke. They were medium-sized boats that were over-crowded with evacuees. Many of the Vyner Brooke’s passengers were the Australian nursing sisters. They were wonderful and I don’t know what we would have done without them in our camps. They were also the ones who suffered the most.

The Giang Bee carried about 300 passengers and had just six lifeboats capable of holding 32 passengers each. We found space in the cargo hold, among sacks of rice and rats. There was just a small hole to provide air.

The next day, Japanese bombers sighted the Giang Bee in the Banka Straits. We were ordered by the ship’s crew to lie face down on the deck. Several evacuees were killed during the raid. The Giang Bee next caught the attention of the Japanese navy as three destroyers raced towards us. In an effort to save us, the Giang Bee’s captain ordered the servicemen on board to throw their weapons into the sea, stopped the engines and struck his ensign to signal surrender. He put the women and children on view on deck but this did not stop the destroyers training their guns on the Giang Bee. The lifeboats were lowered but only two got away. The remaining lifeboats were fired upon by the Japanese. As I jumped from the Giang Bee to a lifeboat, the movement of the waves took the ship in one direction and the lifeboat in the other. I fell between the two, into the sea, cutting my forehead on the side of the lifeboat as I hit the water. I couldn’t swim and would have drowned if a sailor had not caught hold of me by my hair and pulled me into the lifeboat.

It was estimated that 100 passengers were still on board the Giang Bee when one of the Japanese destroyers fired at the boat and that 200 people from our boat died that day. As our lifeboat pulled away from the Giang Bee we saw that it was on fire and starting to sink.

We lost the few possessions we had managed to take with us from KL – including valuable documents such as our birth certificates. We spent two nights in the lifeboat and had one small barrel of water to be shared by approximately 56 people, some of whom were young children. The water was strictly rationed – a sip in the morning and another in the evening. It was so hot in the daytime and chilly at night. I have never liked being out in the sun and hate weather that is too hot. There was no shelter at all from the sun and l burned badly. During the day several people, including me, were so parched that we dipped our hands into the sea and drank what little seawater we were able to cup in our hands. This made us even thirstier and caused blisters to form in and around our mouths. My mother kept telling me not to do this but I was so thirsty I could not stop, even though I regretted doing it.

In the daytime Japanese seaplanes dived low over us and we thought we were going to be machine-gunned. The planes flew so low that we could see the pilots grinning. At night the search lights on the Japanese battleships plagued us and we were convinced we were going to be killed.

On the third day we sighted land – we didn’t know then but it was Banka Island in Sumatra. We were so weak that we could barely drag ourselves ashore. We eventually found some local people who allowed us to have a wash using water from the village well, and gave us rice and salt fish to eat. In payment, my mother parted with her wedding ring. Our total possessions now were only the things we were wearing. If we had had any money it would have been worthless for the locals told us that Singapore had fallen the day before, the 15th, and Singapore dollars were now worthless currency. They also told us that the Japanese had taken Java and they would have to report our presence to the Japanese.

We were allowed to sleep on the beach that night, but we were plagued by ants and mosquitoes. The next day we were escorted through a muddy river inhabited by crocodiles to find the Japanese waiting for us at Muntok. We were held in a room somewhere for a few days before being moved to Muntok Jail.

It was in Muntok Jail that we realised that not all members of the family had arrived. Daddy was already in the jail, but my sister Corinne, who was 14 years old, and my half-brothers Albert, Noel and Clive were missing. The family had become separated in the chaos of evacuation but we had hoped that they had found places in the second lifeboat, the only other one to get away.

Soon after we arrived in Muntok the men, and boys considered old enough to be classed as men, were separated from the women. This was the last time Mummy and we girls saw Daddy.

On leaving Muntok Jail, the women and children were moved from camp to camp – I cannot precisely remember how long we stayed in each. But whatever the camp, the duties were the same. In those high temperatures, under a blazing sun, I dug graves, buried the camp’s dead, dug latrines and took my turn at clearing those out, cut down trees and chopped wood for the fires we used for cooking. Joan, who was only eleven when we were captured, soon also had to help chop wood and dig graves. Maisie was only nine so she was not expected to do any jobs but stayed with Mummy if not attending the ‘school’ run by the Dutch nuns.

I took Mummy’s place on the cooking squad when she became too ill to work. I was doing so much and poor Joan, at such a young age, was also working. When on the cooking squad I had to carry extremely heavy containers of water, rice (which was dirty and contained sand and splinters of glass) and ‘porridge’, actually rice starch from the water the rice had been cooked in. The cooking containers were large metal drums with holes through their sides at the top. A pole was threaded through the holes and two of us would carry the drum by holding the pole. One day we asked for some meat. A few days later the guards came into the “kitchen” laughing and threw a live monkey at us. Hungry as I was, I could not even think of eating the animal. We tried to grow some vegetables to get vitamin C in our diets but this was not so successful and we often used to throw greenery in the cooking pot in desperation for some nutrition and to alleviate the monotony of that awful rice.

Many of the Dutch women in camp had lived locally and arrived with possessions and money. They used to pay others to do jobs for them. I was glad of the little money I got from them as I could buy some extra food for Mummy. But after some time, even the Dutch had nothing left and Joan and I used to give our portions of food to Mummy to try to keep her alive. The Dutch nuns were lovely people and helped everyone.

Kenny (my brother) was placed with us in the women’s camp at the start of internment but after a time he was taken away from us and put in to the men’s camp.

When I was about 17 the Japanese wanted me to go and work in their clubs. I said no and Mummy stepped in front of me, shielding me. She was very ill but she told the Japanese that if I went, she and the rest of my family would go too. The Japanese slapped both of us about our faces and shouted at us to “get out” (of their sight). We hurried back to Joan and Maisie who were crying because they had seen us being slapped. During three and a half years of internment I was hit by the guards a few times – for not bowing low enough to them, for not showing sufficient respect.

The roll calls (Tenko) were times we dreaded. Sometimes they would wake us in the middle of the night for no good reason and make us stand there, counting and re-counting us. But it was the Tenkos in the day – which took place every day – that were the worse. We would have to stand in the baking heat, sometimes for hours, while they counted and re-counted us. If anyone fainted they got very angry and if you tried to assist someone who had fainted or was ill, whatever, you’d find yourself being slapped or hit with their rifle butts. And then they would start counting again.

Not all our guards were cruel. There was one Japanese guard who had a very kind face and he used to try to give us some food occasionally for Mummy because he knew how ill she was and that Joan and I were giving her our meagre portions. I remember he once brought a tin of milk, another time some bread, on another occasion a tin of corned beef and once a banana. If he had been caught doing this he would have been killed. The Korean guards were the worst – they were evil – but so too were the local guards the Japanese brought in to the camp.

I think that in total we were in six or seven camps. They used to move us in the dark, sometimes after midnight, so we never knew where we were going.

We slept on shelves measuring from 18 inches to 26 inches. The conditions were made worse because of the cockroaches that used to share the shelves with us. The highlight of our week was the Saturday night sing-songs organized by the Australian nursing sisters and the concerts given by the Women’s Choir. I think the guards enjoyed our musical evenings as they always came near to the venue and sat quietly listening,

We threw nothing away. The tiniest piece of string, a rusty tin – everything was kept and jealously guarded.

I suffered from the dreaded Banka fever and numerous attacks of malaria. There were two doctors in the camp, Dr McDowell and Dr Smith. They were both very good and used to fight the Japanese to get medicine and drugs. Dr Smith looked after me a lot and was very good to me, fighting the Japanese to give her quinine for my bouts of malaria. Her language was quite strong! I had to try and get better quickly because I had to look after Joan and Maisie, and Kenny, before they took him to the men’s camp. Mummy was just too ill and the doctors thought that if our internment had lasted another week, she would not have survived.

Food and freedom was always our last thought and prayer every night, besides the fear and worry of what tomorrow would bring from the drunken Japs, and who would die next. Starvation, hard work, and living in primitive conditions was our life, and we had to learn to cope, and hope and manage as best we could, which wasn’t always easy. Some were lucky, had money or jewellery and could buy from the black market, but for those of us who lost everything when we were shipwrecked, this was hopeless.

We did not know the war had ended until a week after – on the 22nd August. But we knew something was going on because they suddenly started to give us more and better food. When the allies found us and came in to our camp we discovered that the Japanese had locked away those Red Cross food parcels that they had not eaten themselves, and we also found supplies of medicine that had been so badly needed. We wept for all those lives that could possibly have been saved if the food and medicine, rightfully ours, had been given to us.

I remember the day the Japanese told us that the war was over. The Camp Commander stood on a table and said, “War over. Now we friends.” Dr Smith was standing behind me, supporting me as I had a malaria attack, and she said “Not bloody likely,” which made me laugh.

We discovered then that the men’s camp had been very close. Malcolm and Kenny came to see us, and Elder and Norman to see their wives, Charlotte and Clare, and Felice, who was now almost 4 years old. That was when we learned that Daddy had died of Beriberi on the 11th July 1944. He was buried at Muntok

It was not until the 5th September that we were flown out of Sumatra by the Australian Air Force. We had a visit from an Australian Repatriation Officer who said they would get us of the camp as soon as they could but asked us to be patient as they had a lot to organise.

We had all been fantasising about what we would eat when we got to Singapore. I yearned for a slice of crusty bread and butter. When we landed in Singapore women from the Red Cross met us, offering cups of tea and plates of cake. I was just about to put out my hand to take one when I felt a hand on my shoulder, restraining me, and a voice said, “Nothing to be given to this planeload of internees. They are all going to hospital.” I cried, desperate for a cup of tea and a slice of bread. The only thing I was fed in hospital that first week was an egg. It was a week before I was allowed to eat a whole egg. For three and a half years we had been starved and whatever food we had was of appalling quality. Rich food therefore had to be introduced slowly into our diet so I was given a teaspoon of soft boiled egg a day for the first week. Because I was suffering from malaria I was kept in the British Military Hospital at Alexandra for three weeks. After leaving hospital our family was moved first to Raffles Hotel and from there to the Sime Road Transit camp where we lived until we could find a house to rent.

A note on Clare (Marsh) Boswell, the wife of Norman Boswell.

Clare celebrated her 90th Birthday on the 26/08/2013 in Perth, Western Australia. Her daughter, Valarie (Boswell) Wood, read the poem (below) to her mother as a celebration of her life. Clare lives in her own unit with help from her daughter Felice Ann, carers, and friends.

Clare my Mother

Clare Lelia Boswell nee Marsh was born in August 1923,

In Seremban town, north of JBee,

Her mother Ann was a housewife,

Father William an important JP.

She was their 14th child,

Born to a healthy mix of English, Dutch and Portuguese,

The English called us Eurasian not Heinz 57 which would have been a tease.

She lived on a large estate where life was a dream,

She was young when William died and this ended the family team.Clare moved to KL to live with her brother Joe,

She had to adjust to life with mother Ann in tow.

Life was tough, I can’t say more,

I was born much later,

She soon married Norman, who was to be my Pater.

Clare, Norman and baby Phil survived the war against the cruel Japs,

History was made, told and retold by countless tearful chaps.

Husband Norman worked for Royal Mail,

And sent to study in South Wales,

Clare’s family was now 5 females!!

Norman was always sports mad,

And became the best Malaysian FIFA referee they ever had.

We learnt to watch football and tussle with the crowd,Especially when they chanted, ‘Ref get on your rickshaw and off the field,’ so loud.

Norman gained promotion in his job,

Time flew by and he was soon retired.

Then all too soon he left us, when he sadly died.

With her family scattered, Clare moved to WA,

Into her own flat, got through the good grace of Bishop Hickey,

She became religious, sorted her life and the church’s!!

Giving communion to the housebound and the sickies,

She was secretary to a lady’s church group,

And it surprised me that she enjoyed being in this holy loop.

Taking everything in her stride,

Clare visited us on the UK side.

She looked after baby David.And enjoyed to shop till I dropped,

She made trips around, Rome the latest to Knock,

Within a month she would be back to WA having to alter her clock.

Today Clare is 90,

What a great age,

I am sure she will have something to say,

Enjoy your lunch on this auspicious day.

You are a remarkable lady, mother, grandmother, great grandmother and a friend to us all here, Let’s raise our glasses and say a LOUD cheer,

Clare, my MOTHER, we wish you many more happy and colourful years,

CHEERS! CHEERS! CHEERS!

Clare celebrating, her 90th Birthday on the 26/08/2013 in Perth, Western Australia.