Ruth Russell-Roberts was the wife Denis, an Indian Army officer. Their baby daughter Lynette was safely evacuated to England. Ruth was evacuated on the Mata Hari and died in captivity 18.1.45 [36] at Muntok [CWGC has 20.1.45].

Her husband Denis wrote a book titled: ‘Spotlight on Singapore’ from which most of the passages below, with some edits and additions, have been taken.

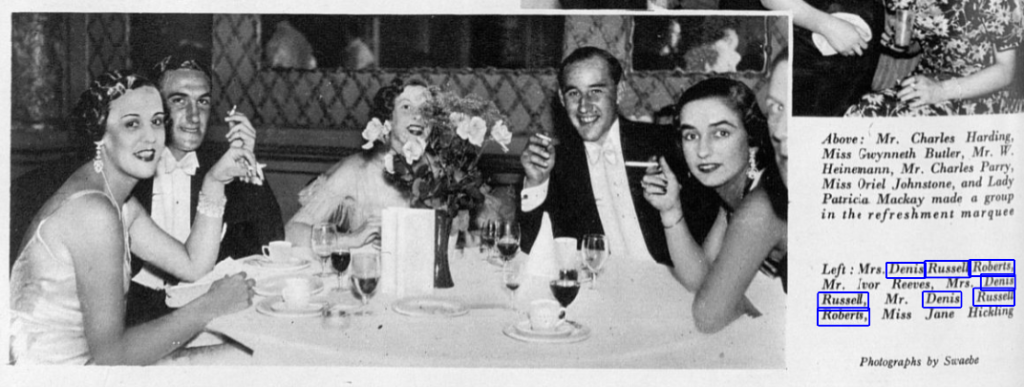

Below: before the war when things were different; Ruth [far left] and a party of friends. The headline reads: 1934: After Lord’s: The Eton and Harrow Ball at Hurlingham.

A major source for these recollections were the conversations that Denis had with Christine Cleveley who was able to give a detailed account of what life was like in the camps and how Ruth experienced them.

Christine kept a diary while in captivity which helped her to recall the events described below. Unlike the other ships, such as the Giang Bee and Vyner Brooke, the Mata Hari escaped being bombed and sunk and so most of its passengers were in better shape when they landed at Muntok.

Below: The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 February 1941.

After the capture of the Mata Hari

We find Ruth and Christine [Cleveley] making their weary way along Muntok’s concrete pier. Carrying all their worldly possessions, they formed part of a long line of struggling people.

With them walked the Italian-born manager of the Singapore Harbour Board, Grixoni, whose wife, Mary, had left for South Africa in January with their two children.

They spent that night huddled in heaps on the pier itself. Ruth had her navy and fawn coloured rug which had been a wedding present eight years earlier, and also her camel-hair overcoat.

Before bedding down, Christine produced one of the tins which Carston [Captain of the Mata Hari] had distributed to his passengers earlier in the day. It was a tin of sardines which, with dry biscuits as a foundation, they ate with relish.

During the night Japanese soldiers walked among them, jeering and laughing at their plight. One of them attempted to get fresh with a Chinese girl, but an elderly English missionary woman fearlessly struck him with an umbrella and he made off sheepishly.

At the sea end of the pier Air Commodore Modin, as senior officer, did his best to create some form of organization out of the chaos. No drinking water was available and only the most primitive arrangements were permitted to be made concerning sanitation. Nevertheless, like most bad things, the night passed and the dawn awakened hope of slightly better things to come.

That hope took them on a long and weary march through the streets of Muntok, and far beyond to a Coolie Assembly Station where they were to be temporarily housed.

This formidable looking Coolie Station consisted of a concrete quadrangle with an iron roof and several long dormitories on either side. Here Ruth and Christine first met with the survivors of some of the sixty ships which had been sunk while approaching the Banka Straits.

And what a spectacle these desperate souls presented, among whom was a party of Australian nurses from Vyner Brooke; two of their number had been swimming in the water for twenty-eight hours and now had their hands and legs covered in bandages.

The others had landed at various places along the beach and had walked into Muntok to give themselves up. They had lost everything; one girl had walked in dressed only in her corsets and a borrowed overcoat. Ruth realised now how lucky she had been to have survived the hazards of the voyage from Singapore.

Later, she had her whole suitcase of possessions stolen, including a silver-fox fur which she had cherished all the way from Singapore, but she was apparently surprisingly cheerful.

They slept side by side on concrete slabs which they called “Macfisheries.” Twenty-five lay on each slab on either side of the dormitory. Though they had a rug each and a lifebelt for a pillow, the hardness of concrete cannot be mastered in a night.

Christine, having been a VAD officer and a trained nurse worked with the regular nurses and doctors in a clinic which had been set up to deal with the sick and wounded.

Ruth, unfortunately, knew nothing about nursing but, wishing to occupy herself profitably, she took on the job of washing bandages and other such menial tasks under Christine’s supervision.

The Japanese dished out handfuls of rice twice a day and an Oriental version of stew accompanied the second issue. There must have been two hundred and fifty women and children in that Coolie Assembly Centre, while at least three hundred men were accommodated in the dormitories on the opposite side of the quadrangle.

One evening in walked four English nursing sisters who had been at sea on rafts for five days. They arrived in a sorry state, sunburnt, blistered and shocked. Then after nearly a week, one Australian sister walked into the building by herself and joined up at once with the other Australian girls. Her arrival was somewhat mysterious and few knew her story. In fact, for the next three and a half years her story remained a secret known only to those few. There was a reason for this.

This girl was Vivian Bullwinkel. With twenty one other Australian Army Nursing Service Sisters, twenty civilian men and women, and twelve ship’s officers and men she had survived the sinking of the Vyner Brooke. The women of this party had been crammed into one of two serviceable lifeboats while the men swam alongside. After many hours at sea they had reached a sandy stretch of beach three miles north of Muntok on Banka Island and there joined up with ten men and women from another sunken ship. At daylight a Japanese patrol arrived on the beach and the party of castaways surrendered. After a furtive discussion among themselves, the Japs took the men prisoners round a small cape and lined them up at the water’s edge, facing the sea. The Japs then opened fire with tommy-guns, mowing the party down in the water. Two of the prisoners plunged into the sea; one was killed while swimming, but the other, Stoker Lloyd, although wounded, managed to get away.

The Japs then returned round the cape to the women prisoners, where the same terrible story was repeated. Sister Bullwinkel describes this dastardly outrage in these words: “The Japs set up a machine-gun on the beach behind us, then with their tommy-guns at the ready they opened fire, mowing us down. I was hit under the ribs on the left side and soon lost consciousness. Then I found I was lying on the beach. Bodies were all around me. I lay there as though I were dead because something told me I would be killed if I moved. I again lost consciousness. On waking I dragged myself into the jungle and there I fainted again from loss of blood and remained unconscious for three days.”

When she came round a Japanese patrol was passing along the pathway within a few feet of her. She could see their faces and their bayonets through the foliage from where she lay. Vivian Bullwinkel was later found by Stoker Lloyd and a handful of survivors from another ship. The latter tended her as best they could. The need, however, for food and medical attention forced the party to give themselves up ten days later. They started to walk towards Muntok and happily for them a Japanese naval officer soon picked them up in a car. After questioning them at Naval headquarters, the Japs brought them to the Coolie Assembly Centre. When Vivian limped into that Coolie Centre at Muntok she was wearing a water bottle slung across her shoulder. It covered a bullet hole in her uniform. Had the Japs ever suspected that she was the lone survivor of that dastardly massacre on the sandy beach near Muntok, her life would have been worthless. The secret was kept and Vivian Bullwinkel came through.

On 2nd March the main party of women and children were taken across the Banka Straits and sixty miles up the Moesi river to Palembang in Sumatra. The doctors asked Christine to stay behind to continue to nurse the sick, and since Ruth did not want to become separated from her, it was arranged that she too should remain behind to help in the clinic.

But the dreaded day dawned some six weeks later, when they too were ordered to leave for Palembang to join the main party of women. They left with the rear party, and as they walked through that drab and friendless town, carrying their possessions, they must have presented a pitiful spectacle. A long wait on the pier was made bearable by the beauty of the sunrise, which was rendered all the more striking by a double rainbow. They were taken out in a launch to a rough and ready tramp steamer.

The Internment camp at Palembang

The internment camp in Palembang consisted of some fifteen small artisan-type houses which had been built along either side of two streets which ran at right angles to one another. Barbed wire had been erected around the outer perimeter of the camp. Each house contained two or three bedrooms in addition to a living-room and dining-room, and outside was a garage. Since about a hundred Dutch women had now joined the party there were approximately three hundred and fifty people to be housed. Roughly twenty-five were therefore allotted to each house.

Ruth and Christine slept on the hard concrete floor, protected by Ruth’s navy and fawn coloured rug and covered by Christine’s Aertex blanket. As the days passed they set to making half-length mattresses from rice sacks which they filled with grass. But mosquitoes made sleeping impossible, so that finally they were forced to make sleeping-bags from material they were able to buy from an Indian merchant who was allowed into the camp once a week.

Christine was a good friend to Ruth. She was far better equipped than Ruth to face up to the kind of life in which they now found themselves, since Christine was essentially practical, capable and proficient, while Ruth’s life in India and the Far East had hardly trained her to become self-sufficient. So Christine took her in hand, and taught her to knit and to cook, and she even cut her hair. In return Ruth gave her friendship, gaiety and affection. They could talk together because the timbre of Christine’s voice came through to Ruth so well, and this was something for which she felt grateful at a time when her deafness was often a troubling defect. The two of them shared a relationship which endured to the end.

Rations came in daily on a truck, the rice crawling with bugs and insects, but spinach, bringals and long beans made it possible to cook one vegetable stew every day … but the girls soon learnt how to make porridge by grinding the rice. They also made what they liked to call cakes and puddings with rice flour, peanuts, palm oil, and odd pineapples, bananas and a sparse ration of sugar.

The supply of wood for cooking proved a big headache. In the early days, various doors were taken off their hinges and chopped into firewood. The first British commandant, Dr Jean McDowell, protested to the Japs in the most courageous way, and it was due to her energy and her fearless manner with the Japanese officers that conditions in the camp improved as much as they did. Apart from her responsibilities as the British commandant she also did a great job as a medical officer. On this occasion her outspoken protestations produced instant results, and a truck was driven into the camp laden with wood in fifteen-foot lengths. This supply then came in twice every day for a week until no one knew quite where to put it. As it all had to be chopped up and as there were only two axes in the camp, the women worked in relays throughout the day. For the first year Ruth and Christine were two of the regulars on this particular chore.

Another headache was lack of soap; the Jap ration of soap was scarcely enough for anyone to keep themselves clean. Happily many of the Dutch women were generously inclined, and a little later one or two local tradesmen were allowed into the camp to sell such things.

Ruth had left Singapore with at least $100 in her purse and was therefore one of the more fortunate ones in this respect. It was practically impossible, however, to replenish stocks of lipstick and cosmetics. On the other hand, one or two of the internees like Christine displayed a natural aptitude for hair cutting, which they did for a small charge and with a skill which appeared to satisfy their customers.

Clothes were, of course, in desperately short supply. Hardly anyone had a hat of any kind, and under a hot sun this was a troublesome deficiency, and shoes were also in short supply. Nearly everyone wore native clogs, but some were content to grow accustomed to walking barefoot. Those with money could buy a length of cloth from the native tradesman and make up a dress themselves. Even patched mosquito nets became a feature of their efforts. Fortunately, a fine communal spirit looked after those in need.

Camp life soon became organised and everyone had to work hard to keep it ticking over. In every house individuals were detailed off for sweeping, washing and cleaning duties, and these embraced the constant clearing of drains both inside and immediately outside the camp.

In House No.7 the presence of a piano proved a tremendous boon, for the camp bristled with musicians and music-lovers. No.7 was occupied by the Australian girls, and early on they held sing-song evenings which became so popular that it was found impossible to accommodate all who wanted to come.

This in turn led to full-scale concerts, which went on improving from week to week and would often include a short play on certain aspects of camp life which invariably roused uproarious laughter.

Church service was held every Sunday in one of the garages and was so well attended that most of the congregation sat outside in the street. The service was taken by one of the English missionaries, and there was always a choir of five.

The evenings seemed long because there was not enough to do. Some of the women made their own playing cards for bridge, and others made complete sets of Mah Jong. But even with the English books which, the Dutch brought in with them, there was insufficient to read. Copies of the local Japanese newspaper were allowed in the camp, but as this was Jap controlled, its contents consisted of fantastic claims in sea battles in the Pacific and little else. French classes were arranged for those who wanted to learn, and the presence in the camp of a number of trained teachers enabled regular educational classes to be held for the children.

When food became scarce, boldness was their friend. Boldness, in fact, possesses even the frailest when hunger sets in. A chance conversation in Malay between Christine and a Chinese across the wire brought the promise of food one night after dark. It was fortunate that House No. 6 backed on to a wood on the far side of the barbed wire fence, so that by keeping a wary eye on the Jap guard they were able to crawl through the wire while he was patrolling the opposite end of the camp. That clandestine meeting took place in a Chinese graveyard. Though the price in money was high, they returned to camp with two well-stocked bundles of food.

So successful was that venture that they boldly repeated the meeting several times with the same result – a good feed. But then they chose the wrong night, when the moon was against them, and they were caught. The face-slapping they expected; it was the interview before Captain Seki on the following day which gave them some concern. Of this Christine glibly writes:

“We took our Jap interview very calmly, we had come to learn that they were afraid of tall women.”

In August one native tradesman was allowed in the camp on Sundays. He used to bring a mobile shop with him, mounted on a bullock cart, and in rows of boxes he would display pineapples, coconuts, limes, and bananas. In other boxes he would have tea, coffee, and sugar. Sometimes he would bring sandshoes and lengths of cloth in his cart. This was Gho Leng.

They also got to know an Indian tailor called Milwani, whom the Japs allowed to come to the Guard House outside the camp from time to time. He brought lengths of materials, cottons and sewing materials, which he sold at a price usually too high for the many who had little money. Only two women at a time were allowed to go outside the wire to buy from Milwani, so his occasional visits lasted most of the day.

About this time, too the Japs became tired of guard duties, so they sent for Javanese policemen and armed them with revolvers. These police boys were dark-skinned natives whom the Japs called Hei Hoes. They were particularly fond of children, they disliked the Japs, and they invariably went to sleep in their sentry boxes when on guard duty. This delegation of duty proved very popular in the camp and made things considerably easier.

Towards the end of 1942 another hundred and fifty Dutch women arrived in the camp, and this meant further overcrowding in every house and garage. Many of the women were the wives and daughters of Dutchmen who were in the highest social and financial circles in Holland before the war. Accustomed to a gracious way of living, they now found themselves crowded into verminous quarters and forced to work as manual labour. This, of course, applied equally to a large number of British women already in the camp, but adversity is a great leveller. The new party of Dutch people soon settled into the life of the camp just as the original party had done, and many of them made notable contributions to the welfare of their fellow prisoners.

Most of us know what it is to feel anxiety for someone one loves. That constant dread, an aching pain inside eats away into your system until you wonder if such things will not ultimately destroy you. Certainly in the war against Japan this aspect of life played a sinister, nauseating role, for the Japs cared nothing for the normal feelings of humanity, and we were therefore starved of news of those we loved, and, just as important, we were denied for nearly two years the means to send them news of ourselves.

In other prison camps, such as Changi in Singapore, the prisoners were never without secret wireless sets through which they were able to keep in touch with events in the outside world. But with Ruth and her companions there was nothing. A curtain of silence had fallen between them and the rest of the world, through which not even the smallest ray of hope could travel. And this agony of silence remained with them throughout. Nor did the Japs make any attempt to allow women prisoners to send a post-card to their next of kin until thirteen months after capture. Two and a half years were to pass before Ruth received news of her daughter Lynette.

Nevertheless these women in adversity showed a remarkable degree of resilience, and neither Ruth nor her fellow prisoners were going to be completely deprived of news of the outside world. Up to this time little messages of hope and encouragement had been concealed in the ration truck which used to visit the civilian prisoners in the jail before coming on to the women’s camp. This bit of luck made it possible for the men to send extra rations to the women by wrapping them up carefully and hiding them in certain places in the truck. Several tins of foodstuffs were sent to Ruth and her closest friends by a young naval officer she had known in Singapore, and with such things were several notes of news from various friends who had known her in those better days before the war.

Later, at the beginning of 1943, the men in the service camp at Mulo School badgered the Japs about cutting wood for the women’s camp, and eventually won their point. This meant that a second truck came into the camp every day with a supply of firewood for the cookhouses, and a system of concealing notes in specially marked blocks of wood was soon working smoothly. Gradually a complete source of news, local as well as international, was built up over the days and weeks which followed and in this way that dreadful silence of the East was pierced here and there for our womenfolk in Sumatra.

But in the first few months of captivity in 1942 Ruth was busy working out some scheme to get a letter to me [her husband Denis Russell-Roberts] in Changi in the belief that I had survived the last three days of fighting on the island. When Gho Leng came into the camp on Sundays she would converse with him in a low voice on the chances of getting a letter taken to Singapore. Though she did not trust Gho Leng she was prepared to use him for her purpose. Gho Leng knew a Chinese whose name, he said, was Ah Wong. This man sailed a junk to Singapore once a month, but to contact him under present circumstances was something Gho Leng was not prepared to do. In any case, he said, Ah Wong was suffering from a poisoned foot and was attending hospital every week for treatment. She asked him which hospital and Gho Leng told her.

Charitas Hospital, some three miles away in Palembang, was run by Dutch nuns and Dutch doctors. This was quite a small hospital, and though the patients slept on mattresses placed on wooden benches and had pillows for their weary heads, lack of ventilation, mosquitoes and suspicious Japanese guards made it a nightmare to be sent there for any length of time. Sick prisoners from all the different camps were nursed in Charitas Hospital. Servicemen from Mulo School camp, civilian prisoners from the jail, and women from the Women’s Internment Camp were all sent to Charitas Hospital. On arrival there they were separated into three groups and were under the strictest surveillance by Japanese guards. The latter patrolled the passages between the wards day and night to see that there was no communication between patients of different groups.

Once a week on Wednesdays it seemed that almost anyone could visit the hospital as an out-patient. It was Wednesdays too that the sick from Ruth’s camp were taken to this hospital in a one-time British ambulance, together with those who merely wanted treatment for lesser troubles and who were returned to camp later in the day in the same ambulance. Toothache and eye trouble were the most popular excuses for inclusion in Wednesday’s ambulance parties, and those who returned were expected to come back with a store of messages from the men prisoners, hidden in their clothing.

So Ruth decided to develop toothache for the purpose of seeing for herself the set-up in this hospital. Her plan was to find Ah Wong, but if she failed to do this, to persuade some other native to ask Ah Wong to be at the hospital the following week. When the ambulance arrived on the Wednesday she found that she was one of twenty-three travelling to the hospital.

When the sick had been officially admitted and put to bed, Ruth found herself waiting with six others in a passage for the Dutch dentist to arrive. Jap guards seemed to be everywhere and she soon realised that to make contact with anyone even inside the hospital was going to be difficult enough, and the man she wanted was more likely to be waiting in the queue outside. Nevertheless, by engaging the Japanese sentry in pidgin English conversation at one end of the passage, Ruth found that it was possible for one of the party to slip away to the one solitary lavatory at the far end of the building.

This unromantic location proved to be unguarded and as such became a meeting place for husbands and wives. It also provided the means of passing notes and written messages between the camps. At the same time a master plan became necessary whereby all Japanese sentries in the passages were kept in earnest pidgin-English conversation while that one lavatory was thus employed. In this way Wednesday visits to Charitas Hospital added a certain spice to life for those who had some share in that master plan. Even on returning to camp the excitement among the children when the “am-ba-lans” drove in was a tonic for all to see, for the contents of those messages invariably provided gossip for several days to come.

But Ruth made a different kind of discovery in that lavatory. She found that by standing on the seat and opening a little glass window high up on the back wall, she overlooked the line of outside patients who were standing in the shade outside. Having once attracted their attention she took comfort in their friendly smiles and beckoned to them to move closer to the window. She enquired about Ah Wong and was told that his foot had healed and that he was no longer visiting the hospital. She spoke to these simple people of her desire to get a letter through to Changi camp in Singapore. She asked them if they could find Ah Wong and they told her they would try. She would be back next Wednesday.

But it was not until her third visit that she was able to speak to Ah Wong from that window. An oldish man; a Chinese with more than the usual number of gold teeth, Ah Wong had a definite limp. Like most Chinese he had a broad serene smile when he spoke. He told Ruth that he would not be leaving for Singapore for several weeks but he would take her letter when he went. He said he would have to give it to a British soldier in Singapore who would take it out to Changi. There were many British soldiers who came every day from Changi to work in the docks. He would meet her at the hospital next week when she would bring the letter. In the last week of May, 1942 Ah Wong set sail for Singapore taking Ruth’s letter with him.

The Attap Hut Camp at Palembang

For the first few months of 1943 the civilian prisoners in the Palembang jail had been building a hutted camp less than a mile from the women’s camp in Palembang. When it was completed the builders themselves were transferred to it from the jail, and here they existed for the next six months. On 17th September, 1943, they evacuated this camp at short notice, and the following day the women prisoners were ordered to move in.

The Japs were never helpful concerning moves and their lack of co-operation on this occasion ran true to form. Only three or four native trucks were allowed to assist with the move of those five hundred women and children and all their possessions of pots and tins, firewood, bundles of rags and clothes. Those who were unable to walk had to ride with the baggage as best they could.

The camp had been constructed on swampy soil and was in fact below sea level, making it cold and damp at night. Due to the fact that the men prisoners had been under the impression that the Japs themselves were to take it over, they had purposely left it in a filthy state, and for the first six days of occupation the new inmates were forced to work harder than ever before, to introduce some semblance of cleanliness. The area of the entire camp was little more than one hundred yards long by forty yards wide, and into this confined space the crudest form of living amenities for more than five hundred souls had been crammed.

Attap-roofed huts had been built along three sides of the rectangular shaped area with a Guard House at the entrance to the camp. On one side of the entrance the camp hospital had been set up while the hut on the opposite side was occupied by fifty Dutch nuns. At one end of the camp both British and Dutch kitchens were established side by side. Two bathrooms for the entire camp consisted of large cement troughs designed for the storage of water. The two lavatories, long cement drains, were merely an extension of the bathrooms.

Sixty to each hut was the best that such accommodation would allow and even this meant lying on a narrow sleeping mat two feet from the ground, side by side like sardines. Personal possessions had to be crowded on to a shelf above each person’s bed space. The huts were not only filthy but vermin infested too and the Japs provided nothing for the extermination of such vermin. Then the attap roofs leaked and a storm would lift the old and rotten attap so that the rain dripped through, causing women and children to sleep on wet boards. After a violent gale it was left to the women to climb on to the roofs of the huts to repair the damage. Then too the sanitary conditions of this camp were deplorably primitive. The services of coolies to clean and empty the tanks and trenches were refused so again these tasks fell upon the inmates.

And when the food became worse work became even heavier. With the departure of the men’s camp, the daily truck of firewood ceased to arrive, and this called for a non-stop roster by day for wood chopping. At this time only one blunt axe was available, the other axe having been declared too dangerous as a result of accidents caused by the head repeatedly flying off the handle.

At the camp elections in July Mrs Hinch was elected camp commandant of the British internees and the Reverend Mother Laurentia became the Dutch commandant. Here were two outstanding people who were to prove themselves worthy of their responsible office over and over again. Mrs Hinch had been a passenger in Giang Bee when it had been sunk in the Banka Straits and was one of those who had arrived with only the clothes she was wearing. An American by birth but married to an Englishman, she had spent the last twenty years in Malaya where her husband had been principal of an Anglo-Chinese school of the Methodist Church in Singapore. He was at this time a prisoner himself in the civilian camp in Changi. Now in captivity she was the ideal person to deal with the Japs, for with her placid temperament, her quiet dignity and her serene manner, she was admirably equipped to stand up to the bullying tactics of her sadistic overlords.

Whenever she found herself called to task over some petty matter which her masters found so infuriating, it was her smile which carried the day. If there was nothing she could reply to their ranting, she would simply smile, and to that charming smile of hers the Japs could find no answer. Here was someone who richly earned the affection and respect of those she championed right through to the end.

Mother Laurentia was another fine character who, despite only a scant knowledge of English soon made herself known among the British internees as well as the Dutch. Tall and upright, dignified, but never forbidding, she also had an enchanting smile.

The Almighty had blessed these two women with an abundant store of common sense, which served them well; it helped them to cope with the many difficult problems which arose from day to day, and to work for the good of everyone in the camp.

Then when the Japs fell to making speeches about the scarcity of food, it was necessary to grow more and more vegetables, not only outside the camp but in every little corner inside as well. The vicious circle of less food demanding more work in order to procure even some food was more than some could stand. Many died and all grew weaker. The money in the camp fund was nearly exhausted and it was hard to buy even little items of food on the black market. Only the Javanese “Hey-hoes” who wanted to be helpful, brought food into the camp at night. With their aid a store of gula Malacca was built up in place of sugar. They also brought in eggs, fruit, biscuits and dried fish but even the “Hey-hoes” wanted payment.

When this sort of situation arises there is only one thing to do for food is more important than even the most priceless possession. You must sell anything and everything you have, to get money with whi.ch to buy food. If you don’t do this you become ill and you die. It is as simple as that. So now it was jewellery which kept the wolf from the door. Rings, watches, brooches, pearls, bracelets, little clocks, each with its secret sentimental story, were passed across the wire in the darkness of the night. The “Hey-hoes” acted as the middlemen and they of course took their cut. There were no lack of buyers from outside: even some of the Jap guards themselves fell for the glitter of a jewel. Ruth had a pair of earrings which I had given her at the time of our marriage, an engagement ring, a bracelet of lucky charms and a second-hand diamond wrist watch. One by one they found their way over the wire until only a three banded emerald ruby and diamond eternity ring, my wedding present to her, was left, and this she meant to keep at all costs.

Valda Godley was one of the first to get ill, and being unable to digest rice, she quickly grew weaker. Her death, though not unexpected, came to Ruth as a great shock, for she had liked and admired Valda and they had always been friends. What had been so painful to Ruth was the realisation that with medicines and food Valda’s life could so easily have been saved. She had watched her growing weaker knowing that she was powerless to help her.

Yet life and laughter still prevailed amongst such things. A certain dogged spirit, which refuses to accept defeat under any circumstances, invariably comes to the fore in times like these. It may be that people in such straits are spiritually strengthened by some unseen hand of which they are unaware. Whatever it may be the fact remains that this hapless camp of women refused to be beaten by adversity. Rather did they hurl back defiance proudly and bravely, and seek to sustain their spirit against all misfortune.

So they took refuge in music. It was Norah Chambers who first gathered round her those with singing voices, and practiced them in the Dutch kitchen at night. They had no musical instruments, only voices. Gradually Norah, built up an orchestra of women’s voices until thirty women of many nationalities were taking part and Ruth was one of these. The effect of an orchestra was created by humming the four parts of soprano, second soprano, contralto and second contralto representing the four instruments of strings i.e. violin, viola, cello and double bass.

Betty Jeffrey, the Australian nursing sister who wrote ‘White Coolies’, writes:

“I have been a keen listener for a long time, but now I am a member of the orchestra. It is absolutely marvellous, the most fascinating thing that has happened in this camp so far. None of us has ever heard women’s voices anywhere better than this orchestra. The music is written out on any kind of paper obtainable; each person has her own copy, all being copies from Miss Dryburgh’s hand-made original.

“To sit on logs or stools or tables in the crude old attap roofed kitchen, with only one light, and then be lifted right out of that atmosphere with this music – sheer joy. It makes it easy to forget one is a prisoner.”

The first concert the orchestra gave they did the ‘Largo, Andante Cantabile,’ Mendelssohn’s ‘Songs Without Words,’ a Brahms Waltz, ‘Londonderry Air,’ Debussy’s ‘Reverie,’ Beethoven’s

‘Minuet’ and ‘To a Wild Rose.’ Mrs Murray, with her glorious soprano voice, sang the Fairy Song from ‘The Immortal Hour.’ It was a glorious concert, we had never heard anything like it before.”

Perhaps in this we can see the triumph of the human spirit over all the vileness of those terrible times. Not only with music did they fight adversity. Life went on in other ways too, with religious discussions, prayer meetings and lectures. Birthdays were remembered in a simple but touching way. The children’s classes still went on, and so did the constant war on bugs. Even “Midnight,” the black cat who had no tail, strove hard to keep the rats from knocking bottles off the shelf above the bed mats. Somehow the heart of the camp continued to beat.

Towards the latter half of 1944 one or two rays of sunshine came peeping through the gloom. First a batch of letters from the outside world brought Ruth the news of Lynette’s safe arrival in England. On the same day one British plane dived over the town of Palembang before climbing up again into the clouds. The significance of that visit was not lost among those who had prayed for so long.

Then followed American Red Cross boxes which arrived from apparently nowhere. All through a hot afternoon, while working her turn in the cookhouse, Ruth watched the Japs and “Heyhoes” unwrapping packets of Chesterfield and Camel cigarettes, cans of foodstuffs and packets of this and that. In the evening opened boxes were brought into the camp so that the canteen committee could distribute their contents. When you have been starving for a long time such unaccustomed joys as meat, jam, butter and condensed milk seem like manna from heaven, even though their distribution may leave so small a portion with the individual. The share-out completed each prisoner found herself blessed with twenty-two cigarettes, one inch of chocolate, four lumps of sugar, and a spoonful of butter. The prospect of a share with fourteen others in a half pound tin of Jam gave each of them further cause to smile.

The Return to Muntok

At the beginning of October 1944 the Japs ordered the entire camp to move back to Muntok. Though no one could feel sorry about leaving that sordid camp in Palembang, they all knew that there could be no certainty that the future would hold better things in store.

They left on a hot and sticky day with no protection on deck from the burning rays of the sun. Later the rain came down in buckets so that everyone was soon drenched to the skin. A one hour wait on the wharf at Muntok in wet clothes did nothing to alleviate their plight. Hungry, cold and tired, they were then herded into open trucks and driven at breakneck speed to their new camp outside the town.

Thirty-one months had gone by since they had last passed through the streets of Muntok. How many more lay ahead?

The new camp outside Muntok promised well. After the verminous squalor of Palembang Ruth found that being situated on a hill, it was sufficiently above sea level for the inmates to enjoy the freshness of the sea air, and the attap huts were newer, larger and cleaner.

The men in the Palembang camps had also been moved across to Muntok and were now back in the old Coolie Assembly Centre where they had started nearly three years previously. Somehow they had brow-beaten the Japs into letting them send food to the women’s camp so that when Ruth and her fellow prisoners arrived, there for once was a worthwhile meal to greet them.

The camp had nine wells, but the water soon ran out. This called for more water fatigues, which meant fetching water from a tiny creek about ten minutes walking distance from the camp. Although arduous, this fatigue had its attraction, for the creek was situated beyond a stretch of jungle country in which a number of wild flowers flourished, while the creek itself offered an incomparable opportunity to bathe and wash.

Ruth and Christine soon found themselves members of a party ordered to put a barbed wire fence round the hospital. A week later they were carrying garbage, including broken plates, tins and eggshells to sprinkle on the sweet potato plants. Then the Japs intensified work on the gardens because of the great scarcity of food all over the East, and more and more women were forced to go out of camp every day with chunkals [a kind of hoe] to help grow sweet potatoes in an ever-increasing acreage.

The Dutch worked in their own plot alongside but separate from the British. One of the Dutch women was Johanna Grootes-Honig, with whom Ruth quickly became friendly. In the evenings she would walk over to Ruth’s hut to have a chat with her, then together they would brew a mug of strong black coffee by the light of the one oil lamp shared by one hundred and forty in the hut. Very lovely those evenings were too, for nothing had changed the moon and the stars. Little Christian, Johanna’s six-year-old son, would often accompany his mother on those visits.

Those days in Muntok were hot and humid, and the nights were cold. Three years on a starvation diet had already taken more than fifty lives. But now a fever fell upon the camp with dreadful effect. Some called it malaria, others called it dengue, and finally they named it Banka fever. More and more got ill, yet the life of the camp had to go on.

Four doctors – all women – and a team of British and Australian nurses were continually on duty. Dutch nuns, who had formerly worked as nurses in Charitas Hospital in Palembang, continued to staff the hospital that was now better organized than ever before. The hospital hut could accommodate two dozen patients lying side by side on the “bali bali” shelf of thin branches. In the children’s ward someone had procured two old cots for babies, while the older children lay on the “bali bali” shelf.

The nuns worked heroically. One of them did all the laundry for the hospital and the sick in an oil drum. Another nun spent her entire time cooking for the sick and making hot drinks for the very ill. Like the nurses in the last days of Singapore those nuns behaved like angels.

Yet by December two hundred and ten women prisoners had gone down with Banka fever, and among these the greatly loved Miss Dryburgh lay for weeks on her bed growing weaker and weaker. Her eventual death affected every member of the camp for she had played a noble part in the lives of each one of them. It was she who had initiated and trained that orchestra of voices among the women. Equally gifted as an artist, there was someone of sterling quality whose name should be greatly honoured.

Just before Christmas, Ruth and Christine both went down with Banka fever. Carried to the hospital they lay side by side on the “bali bali” platform. Johanna Grootes-Honig came to visit them every evening, bringing with her little extras in the way of food. But now money was running short and black market prices were rising rapidly. They all had desperate need of money in order to buy food to survive.

Somewhere in the camp a Dutch woman with a natural flair for business was running a black market racket with the natives beyond the wire. Madam Kleines had owned a tailor’s shop with her husband before the war and still had valuable contacts among the natives in Sumatra and at Muntok. A pretty Indonesian girl of twenty called Julia Roos worked for Madam Kleines on a commission basis. Julia it was who crawled through the wire after dark to carry on the dangerous part of the business.

In this way Auntie Priel, as Madam Kleines had come to be known, ran a desperate business under the very noses of the Japs. For every item of clothing and jewellery going out of the camp, greatly needed supplies of food came in. One sarong going out would mean twenty-five eggs coming in; for a gold ring passing over the wire the natives would bring to Julia’s meeting place supplies of sugar, vegetables and fish. The Hey hoe guards were glad to turn a blind eye provided a middle-man commission reached their pockets. It was as simple as that. Only Japanese patrols outside the wire threatened Auntie Priel and her fight to save lines within.

But for all her efforts and despite the nightly courage of Julia Roos, Auntie Priel fought a losing battle. Christmas passed in mourning the dead. By the New Year seventy-seven bodies had been carried out to the cemetery and little Christian Grootes-Honig was one of these. Christine had grown stronger and was able to return to her hut but Ruth lay in the throes of that fever, weak and helpless.

Once the New Year had dawned Johanna Grootes-Honig set about arranging the sale of Ruth’s three-banded eternity ring. During the afternoon of 18th January Aunt Priel sent for Julia Roos to warn her that “a job” had been fixed for that night. On this occasion one of the Hey hoe guards had been bought. Aunt Priel had shown him the eternity ring in return for which the Hey hoe promised to bring into camp such things as eggs, coffee, sugar and vegetables as well as money. It was agreed that Julia Roos should meet him at the usual rendezvous at nine o’clock.

That night a Jap patrol passed within a few feet of Julia’s meeting place, causing the Hey hoe guard to take fright. This left Julia alone among the trees nervously awaiting the arrival of a native with the food. In her own words she writes: “I waited alone for many moments but no one came. Then suddenly I saw a man standing only five yards from me. He had a bald head and broad shoulders. I felt there was something wrong. ‘Come closer,’ he called to me in the local language, and then I felt a hand which had been drenched in oil. I Jumped backwards and ran as fast as my legs would carry me with this Jap behind me. I had to climb over a stone wall on which barbed wire had been erected and in doing so I cut my legs but I was free from the Jap.”

The following night Julia tried again, this time taking another Indonesian girl with her. But before they had reached the usual meeting place they saw before them a man. “He spoke to me in the Muntok language,” she says, “and told me that he carried a letter for a lady in the camp. “You can read on the letter the address,” he said, and then disappeared. Placing the letter in the pocket of her jacket, Julia and her companion then sat down to await the arrival of the native who was due to bring the expected foodstuffs. By ten o’clock they were back in camp, and both food and letter were then handed over to Aunt Priel.

Later that night Christine read my letter to Ruth. She simply nodded and smiled, turned over on to her left side and fell into a deep sleep.

The next day they buried her in that cemetery with the wild Jungle flowers and marked her grave with a small wooden cross.