Richard Henry Cozens Prior was born in 1883 at Portsea Island, Hampshire, the son of a solicitor George Prior and his wife Gertrude. He went to Malaya 1907. He was a Rubber Regulation Officer at Kuala Kangsar. His wife Violet Lillian was evacuated to Natal, South Africa.

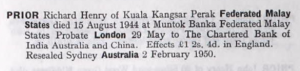

Prior died on 15th August 1944, aged 61, at Muntok of beriberi. His grave is F27 on the Graves page. The “Jeyes” list shows “…PRIOR BRITISH ISRAELITE AT P’BANG…”. Below his probate record: Prior is mentioned quite extensively by William McDougall in his book ‘By Eastern Windows’ and the following passages referring to Prior have been extracted from McDougall’s book, as follows:

Prior is mentioned quite extensively by William McDougall in his book ‘By Eastern Windows’ and the following passages referring to Prior have been extracted from McDougall’s book, as follows:

Second in command to Doc West in the other half of the hospital— the dysentery ward— was Old Pop, 58-year-old English ex-planter whom we called “The Matron.”

Matron Pop was one of the happiest men in jail, probably because for the first time in years he found himself in charge of something and indispensable. His adult life had been spent in Sumatra and Malaya as a planter but he had never attained full managership of a plantation. In fact, he had considered himself fortunate to land a job in the government rubber restriction office. He was a humble man who joked about his failures and whose reminiscences were never sour. He told my favorite Malay baby story.

First you must remember the Malay words for “Hello Mister,” which are “tabe tuan” and pronounced tah-bay too-ahn. Got it? Hello Mister— Tabe Tuan.

Pop was walking a jungle path between plantations and came to a flimsy suspension bridge of bamboo over a deep stream. Pop always came to that bridge with trepidation because its swaying and swinging required a nice sense of balance and a firm grip on the rope handrail. This particular morning he approached it on one side just as a Malay woman carrying a child started across from the other. The baby was having his morning breakfast at his mother’s breast. To Pop’s experienced eye the child looked about two years old, an uncommon age for breast nursing but not infrequent in the Orient. The nursing continued as the mother cat walked across the swinging bridge without using the handrail because one hand steadied the baby astraddle her hip and the other held a basket balanced on her head. She was chewing betel nut and casually spat into the stream.

What startled Pop was the child. In one hand the infant held a lighted cigarette and was alternately mouthing his mother’s breast and puffing on the nipa straw. When the mother had crossed and the astonished Pop stepped aside to let her step off the bridge, the child removed the cigarette from his mouth, exhaled a gust of smoke, looked brightly at Pop and said,

“Tabe tuan.’’

Pop had taken charge of nursing the dysentery patients before they arrived in Palembang Jail and he continued in the job afterward. He slept on the floor of the clinic, or, if he took a notion, curled up on the floor of the dysentery ward. He could have had a door for a bed and even a mattress when a patient died who owned one, but he preferred only an empty rice bag. “Less trouble,” he explained. “All I have to do is hang it on the fence in the morning.” The most nauseating jobs never fazed Pop. He always ate in the ward without a stomach flutter. He reveled in adversity and was happy to be on his bare feet, moving all day except during the siesta hour immediately after the midday meal. Then he slept for an hour while the dysentery rags were being washed and boiled.

[When Prior became too ill to carry on as ‘Matron’ his place was taken by Kendall]

Part 2

There is something about a peaceful heart that communicates itself to others. At the end of a man’s life, possession of such peace is reward beyond measure for whatever it cost him. And nothing can compensate for its absence.

All of which is by way of introducing the stories of some of the men who died in Muntok Prison hospital.

If Old Pop, down-on-his-luck rubber planter who was our first ward “matron” in Palembang Jail, could have known it, he would have considered it some sort of omen when the rope broke as we lowered his coffin into a grave in Muntok cemetery. But he was inside and so knew nothing of being dropped instead of lowered respectfully and gently into the hole as we intended.

Luckily, the fragile, bulging box did not burst and spill its contents of beri-beri swollen flesh. There was only a bump, a crunch of wood and a sodden noise as Pop’s bulk jolted roughly to rest.

“Remember man, that thou art dust . . intoned Hammet, throwing a handful of earth into the grave. Other little showers of earth rattled on the box as we each tossed our parting tribute. Then, rubbing sore shoulders on which the coffin had rested during the mile-long, weary march from jail to cemetery, we retraced our steps.

There was little conversation. Pop’s passing had touched us more than most. It seemed only yesterday instead of two and a half years ago that he had joined us in Palembang Jail and become an institution of bedpans and prophecy. The two were inseparable in Pop’s case as he ran the dysentery ward and read his Bible, drawing therefrom prophecies concerning us and the war.

Quoting scriptural passages he forecast when the first American planes would roar overhead, when the war would end and when we would be released. Our good-natured jeers did not in the least perturb him when the dates arrived without fulfillment of his predictions.

“I see where I made my mistake,” Pop would admit. “I misread that passage in Revelations by six months. But I’m sure of my interpretation now; we’ll be out of here in another six months.”

Then he would quote the passage and explain his interpretation. Another six months would pass and we would remind Pop of his prophecy.

“How do we know the war hasn’t ended?” he would say. “Fighting could be over months before we’d learn about it in this backwater. Besides, it says in Revelations . . .”

And he would be off again on his favorite theme. All his dates came and went eventlessly but Pop was never discouraged, nor his faith in his prophetical ability shaken. We wished, as we buried him, that he still was around to prophesy. He was a good fellow, rotund, merry, fuss-budget Pop, matron of the Palembang Jail dysentery ward, prophet and perpetual optimist.

Pop’s only belongings when I met him were a small suitcase— empty— a Bible, a cheap watch, a knitted green shawl and the shirt and shorts he wore. When he died, the only additions to his possessions were a few tins and coconut shells. Almost all prisoners acquired belongings during their internment but not Pop. He wanted nothing but to rule his domain of bedpans. He ran it, until sickness relieved him of the job, like a fussy old hen mothering a brood of scabby chicks.

Although as ward matron Pop could have enjoyed the prerogative of a wooden door for a bed, he preferred throwing a rice sack on the cement floor and lying on it. Always barefoot, he never wore sandals despite frequently infected feet. Another idiosyncrasy was a pretense of fasting one day a week. He drew his food on that day ostensibly to give a sick friend. While we ate he busied himself with hospital tasks and all day reminded us he had not eaten. At night, when he thought no one could see him, he ate. Next day he would tell us how fit he felt despite twenty-four hours without food.

Pop chattered incessantly. We got so the only times we heard him were when he was suddenly silent; then, startled, we would look around. Two things were possible. Either he had fallen asleep or was studying his Bible for another prophecy.

Pop actually worked only the first nine months of captivity. The rest of the time he was a patient. But he had become a tradition, a part of our surroundings, a sort of gossipy, flesh and blood family skeleton.

On his birthday in October 1943, I gave him a cigar for which I had searched the prison. Beissel finally got it for me from a guard. It was a rank, native-made cheroot but it was the first one Pop had smoked in eight months and he always said he preferred a cigar to a meal. The old boy was as tickled by the fact some one remembered his birthday as by the cheroot.

‘”Mac,” he said, “this cigar is so good I’ll let you in on a secret. I’ve been lying here re-interpreting the scriptures and I have figured out exactly when the war will end. This is an unqualified prophecy. You can write it down. Germany will collapse between October 20th and November yth. Japan will surrender just before Germany does.”

“You mean this year or next year?” I asked. “Tomorrow is October 20th.”

“This year of 1943” Pop emphasized. “This very week. At this very minute Germany may be seeking an armistice.”

He picked up his Bible.

“It says right here in the Book of Daniel, ‘Blessed is he that waiteth and cometh to the thirteen hundred and thirty-fifth day.’ Now their calendar in those days was just a little off. Adjusting their calculations to what we know now . . .”

“Wait a minute, Pop. What’s the Bible counting from? Thirteen hundred and thirty-five days from what?”

“Munich, of course,”

“Munich? Is Munich in the Bible?”

“It says in the thirteenth chapter of Revelations: ‘And power was given him to continue forty and two months.’ Now, my interpretation is that ‘him’ means England. Hitler is the beast referred to earlier in the chapter and Japan is the second beast. In other words, England at Munich gave Hitler, the beast, power to continue for thirteen hundred and thirty-five days.”

“Hold on, pal. Let me get this straight. Do you mean that tomorrow, October 20th, 1943, is the thirteen hundred and thirty-fifth day since Munich?”

“Not exactly, but you see, we have to make certain adjustments for the differences between the calendars of the Old Testament and now. According to my calculations, this week is the time meant. This very week! Of course, it will take a few more weeks for the Allies to find us here and release us. You wait and see, Mac. We’ll be free in a couple weeks.”

The weeks passed and the months, nine of them. Pop became so heavy with liquid it required two men to lift him so we could change the dripping mats beneath him and put them in the sun to dry.

“You know, Mac,” he said in July 1944, “my calculations were off on that thirteen hundred and thirty-fifth day. I’ve been thinking it over and I’m positive it will come in October this year. But I probably won’t see it. I won’t live that long. When your American friends come here in October to liberate the camp, say hello to them for me and remember that I predicted the date.”

“I sure will. Pop, but you’ll be here when they come.”

“Don’t talk nonsense. Of course I won’t. I know how sick I am. And I’m quite ready to go.”

He died, in August 1944, just one year short of V-J Day. Had his bulk been solid it would not have gone in the narrow coffin, but, like a massive sponge, it could be squeezed here and expanded there to fit. Pallbearers included his fellow workers, Kendall, who succeeded him as matron. Doc West, Harrison, Thomson, Drysdale and myself. Because the weight was so heavy we changed frequently with our alternates during the march. The day was hot; sweat poured from us so freely we hardly noticed that some of the moisture which soaked our shoulders was not perspiration but leaked from the coffin. Beri-beri sweat did not stop even in death. We were glad to reach the cemetery.

In a further edition of By Eastern Windows published as If I get Out Alive which gives more details of prison life McDougall writes of Prior’s death as follows:

R H Prior 60 picturesque character of Palembang Jail dysentery days, died 8/15, 11 p.m. [of] beri beri. He appeared aware of his danger, before losing senses completely, & took it quite matter of factly.

By the time Prior died 40 British and 40 Dutch in total had died at Muntok.

EARLIER HISTORY

The Prior family is on the 1891 census: Head George Prior, wife Clara. Seven children: John – Twins Francis and Leslie, Richard, Montagu, Kathleen, and Stanley a Boarder Jane Seplings, a Governess, and two domestic servants.

1901 Census

His brother John Cromwell Cosens Prior was a solicitor. His father George Cozins Prior appears on the 1861 census: