Every year a Commemorative Service takes place at Muntok and Radji Beach to remember the 21 Australian Army Nurses and many others who were brutally executed by Japanese soldiers on Radji Beach on 16 February 1942.

But not all who surrendered to Japanese soldiers died that fateful day. There were in fact 4 survivors of the Japanese brutality of whom 3 survived the war.

Stoker Ernest Lloyd was on board the Vyner Brooke when it was sunk in the Bangka Straits on 14 February 1942. He was a young Royal Navy sailor who could be called the great survivor, or the man who would not die.

“This is where you get it Ernie, right in the back”. (1)

This is the true and almost unbelievable story of the great survivor; Stoker Ernest Lloyd.

Amongst the absolute horror on Radji Beach on the morning of the 16th February 1942, three people lived and in due course, told the world of the ruthless brutality of the Japanese soldiers on that fateful day when so many people were executed.

Two of these who survived the war were Sister Vivian Bullwinkel and Eric Germann, an American civilian. Another man, Private Cecil Kinsley was severely injured when his ship was sunk and then survived being bayoneted by Japanese soldiers on Radji Beach. He died however a few weeks later after he and Vivian Bullwinkel surrendered to the Japanese.

The third person to live through the war was Stoker Ernest Lloyd Royal Navy who was destined to survive; despite the absolute overwhelming odds against such a possibility.

Ernest firstly survived the sinking of HMS Prince of Wales on 10 December 1941, secondly the sinking of the “SS Vyner Brooke” on the 14th February 1942, thirdly the killings on Radji Beach on the 16th February, and finally a very harsh and barbaric 3 ½ years as a Prisoner of War of the Japanese.

Nothing was going to keep Ernest from resuming life again with his very young bride whom he married in Capetown South Africa in August 1941, when she was only 19, just before he left for the Far East on HMS Prince of Wales.

Ernest Lloyd was born in Manchester, England in 1916 and was the youngest son of 9 children. The surname Lloyd came from his Welsh father, who was a talented stonemason. At a young age he walked and hitchhiked from Manchester to London looking for work.

He was homeless during this time and without work he used to steal and eat raw vegetables from farmers’ fields for food. He would recall to his grandchildren an occasion when a fish and chip shop owner took pity on him and gave him a free bag of hot chips; kindness he never forgot. In later life he bestowed the same kindness where he could, and would always give lifts to hitchhikers.

Ernest joined the Royal Navy in 1933. He said to his grandchildren that as well as providing him with a bed every night, it saved his life and he was very proud to be a part of the Navy. During World War 2 he served on a number of ships, and was involved in the Battle of Narvik (Norway) in 1940.

When his ship docked in Capetown in the summer of 1941 he met his future wife. Although known as Muriel to her family and friends her name was Jacobmina Jansen van Rensberg. Muriel was an Afrikaaner who was born in Capetown. At a railway station Ernest asked whether she knew if there was a dance on that night!

They married soon after in August 1941, despite family opposition. She was 19, Ernest was English and memories of the Boer War were still very much alive! The couple applied to the Court for permission to marry which was refused. Finally, Muriel’s Aunt gave permission and they were married. During the war, Muriel lived with her family in Capetown.

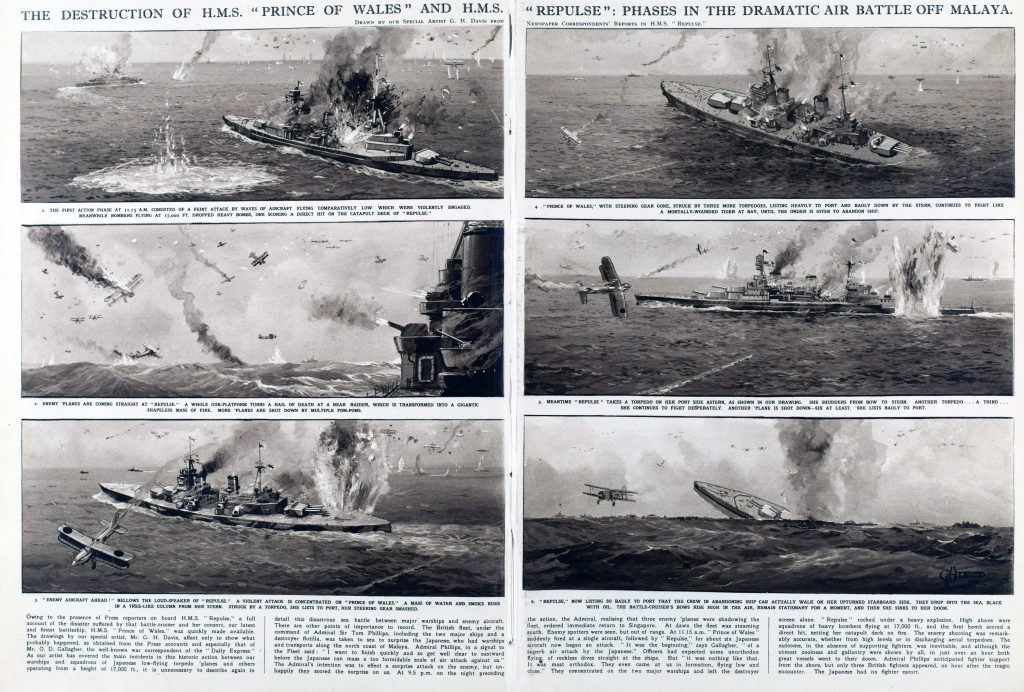

Ernest was posted shortly after to HMS Prince of Wales that sailed for Singapore with HMS Repulse and assorted escort ships. It is history that both these capital ships were sunk by Japanese aircraft on 10 December 1941 near Kuantan in the South China Sea.

Ernest was rescued and spent some time driving lorries around Singapore, ‘taking supplies to Naval personnel and later bringing Naval personnel into Singapore from outlying gun positions to the Union Jack Club, where they had to assemble prior to evacuation’. (as quoted in The Will to Live, p100)

He was posted as a Naval Rating on the “SS Vyner Brooke”. Ernest said

‘After the sinking… I found myself in one of only two serviceable lifeboats…..In addition to the full load of people ….we got hold of two rafts and tied them to the stern of the boat and picked up as many people as we could, including a woman with a very small baby. It was very hard work as I and two others were the only people fit to do the rowing. The others were all women and children or wounded men….It was dark before we got there (Radji Beach)…….We had very little to eat except hard ship’s biscuits and tins of condense milk which had been washed ashore from the wrecks of ships in the area’. (as quoted in The Will to Live, p100/101)

On the 16th February 1942 he was amongst the naval and army ratings that were lined up on Radji Beach to be executed by the Japanese patrol. He was in the first group taken behind the rocks on the headland and was at the end of the line. The man next to him (stated by Lloyd to be ‘Jock’ McGlurk, but research has now shown to be Able Seaman Hamilton McClurg) said, whispering out of the side of his mouth, “This is where you get it Ernie, right in the back”. Lloyd replied “Not for me”.

Both men and a third man ran into the sea and managed to swim about 30 yards before Lloyd saw his companion McClurk killed by a bullet. Ernie said “They mowed down the others first and then turned the gun on the three of us. I was a powerful swimmer and was going well. Jock (McClurg) cried out, “I’m hit Ernie” and both he and the other man sank out of sight. I then got the Japs undivided attention; they weren’t going to leave anyone alive”. (as quoted in The Will to Live, p103)

According to “On Radji Beach” a bullet creased Lloyd’s scalp and another passed through his leg and lodged in his shoulder. His head wound caused Lloyd to become unconscious and he drifted away regaining consciousness and swimming out to sea before ending up at the other end of the beach. He was shot 3 times and his grandchildren distinctly remember him showing his scars to them when kids, which greatly fascinated them.

Ernest remained free for about ten days, with the help of locals and he ‘found some coconuts and a freshwater stream’. After a few days he thought he should ‘walk back along the beach to see if any of the others had survived…..It was quite horrible. All the male bodies had been piled on top of one another in one big heap.’

‘Then I went further along and found the bodies of the Australian nurses and other women. They lay at intervals of a few yards; in different positions and in various stages of undress. They had all been shot and then bayoneted. It was a shocking sight’. (as quoted in The Will to Live, p104)

After a few more days he surrendered and was taken to Muntok. He used to tell his grandchildren the story of coming face to face with a tiger while in the jungle “on the run”! As he was witness to a war crime, while he was a POW he had to hide the fact he had survived the Radji Beach massacre.

Ernest was very open with his family about his experiences for 3 1/2 years as a POW. He was often starving and he talked about the lack of food and of rice mixed with stones. His grandchildren remember that he always hated to see food thrown away and would eat any food left on their plates.

He had dreadful problems with his teeth due to malnourishment and had to have some pulled out with pliers and no anaesthetic; hence his phobia of the dentist which he only overcame late in life. They also recall him telling about the operations to remove infected limbs or parts of limbs, which were carried out by the POW doctors, in the camp without anaesthetic and will makeshift surgical instruments. He contracted malaria in the camps and suffered attacks in later life.

Ernest was beaten badly on a number of occasions. After the war, and for the rest of his life, he suffered bad nightmares about these beatings. He also spent time in the bamboo cages and told his family about the pain of not being able to sit, stand or lie down for hours on end in the sun; sometimes even days.

A lasting effect of the camp was that he preferred to sleep on the floor. He said that it was horrible when you woke up in the morning and your friend next to you had died or been taken away, possibly by the Kempetai, the Japanese military police. He had a life-long dislike of cats because they used to dig up the bodies of dead POWs.

When the Japs surrendered and the guards left, the prisoners found food, medicine and Red Cross parcels which could have saved so many lives. As it was logistically difficult to quickly transport all the POWs and internees out of the camps across SE Asia, Ernest was not air lifted straight away. Food was dropped by Allied planes and he was always grateful to the men who did this.

Ernest said that because he was so thin the flight to Singapore was very uncomfortable which no doubt contributed to his refusal to fly anywhere after that! On 19 September 1945 in the Airport canteen in Singapore Ernest met up again with fellow Radji Beach survivor Eric Germann. The first time had been in Muntok prison in 1942 when they both congratulated each other on their miraculous escapes from the Radji Beach massacre.

Back in Singapore he went to the Long Bar at Raffles Hotel and was refused service as he was not an officer, which was a pre-war convention. He told his grandchildren that an officer said to the barman “Can’t you see he’s a POW. Serve him.” Ernest then claimed to have lifted the barman up by his lapels!

He later gave evidence about the Radji Beach massacre and then returned to Manchester, where he was joined by his wife. They had one daughter, Evis and when she was a few years old they moved to South Africa where he worked in the steel works. In the early 1960s they moved to Wales and he worked at the Spencer Steel Works at Newport.

Ernest attended many naval reunions, and was an active member of the Burma Star Association. Although he met many Germans who had been on the other side of battles in which he had fought, he never forgave the Japanese and would never buy anything Japanese from a TV to a car.

Despite what he had been through, his grandchildren said that Ernest was kind, caring and giving, who would always see the humour in a situation. He was a strong character who never felt self-pity and who would put things into perspective by saying “worse things happened at sea”!

They believe that Ernest was the best, most loving Grandad anyone could ever want. He absolutely adored his grandchildren, would do anything for them, and they loved him equally in return. He was a huge part of their lives growing up, and they would see him almost every day of the week.

Ernest died from a stroke in March 1991 at the age of 74.

Ernest’s granddaughters say that he is remembered by his family “as an extraordinary, ordinary man, who is still very much missed”.

Surely, no better epitaph.

It was wonderful that Helen Webb and Sarah McCarthy, two of Ernest’s loving granddaughters were able to attend the Commemorative events at Muntok and Radji Beach on 16th February 2017.

Sadly, Sarah died in 2022 and was remembered at the Commemoration Service at the Nurses Memorial on 16th February 2023.

Principal Sources:

- (1) The Will to Live p102

- The Will to Live by Sir John Smyth

- Michael Pether Auckland New Zealand

- On Radji Beach by Ian Shaw

- Recollections of his grandchildren