Two members of the Hobbs family were interned at Palembang, Muntok, and Belalau and they were:

Robert Neal Hobbs who was born in 1899 at Dubbs, New South Wales. He was a race-horse trainer and winner of the Governor’s Gold Cup, Singapore in 1938. He was aged 43 in 1942. He was captured aboard the Mata Hari.

His wife was evacuated on Charon with daughter Joyce L. & son A .E., arriving at Fremantle, Western Australia on 18.1.42. He survived internment and returned to horse racing in Singapore post-war. Robert died in 1967 at Penrith NSW. Other children were Audrey & Neal. Neal was interned with his father.

Neal Howard Hobbs was born in 1924 at Kuala Lumpur – son of Robert (above). Educated at the Victoria Institution. He was a student aged 17 in 1942 when he was captured aboard the Mata Hari. He returned to Malaya post war and now lives in Brisbane 2016. [See also Neal’s recollection of Maurice Lionel Phillips]

THE NEAL HOWARD HOBBS STORY – WARTIME EXPERIENCES

I was living in Kuala Lumpur at the time the Japanese invaded the country in December 1941. Their forces soon gained a foothold and moved rapidly down the peninsula towards Singapore.

This resulted in a steady stream of people trying to escape via Singapore in January and early February 1942. Singapore, of course, surrendered on 15th February.

Amongst the panic stricken citizens anxious to get away were my father and I. (My mother and two sisters had left for Perth on MV “Charon” on 10th January). We managed to embark on 12th February on a vessel named “Mata Hari”, tonnage 800 approximately. Two other ships of similar size joined us in convoy. These were “Vyner Brooke” and “Giang Bee”. The former had on board the Australian nurses about whom a lot would later be written.

Moving through the minefields off Singapore our vessel lost its way and when it finally reached safe waters the other two ships were several hours ahead. This undoubtedly saved us from the same fate as the other two met. They were sunk by Japanese bombers off Bangka Island.

The sinking of “Vyner Brooke” subsequently resulted in the massacre of 21 nurses on a beach at Bangka. A sole survivor was Sister Vivian Bullwinkel. Of the 65 nurses who left Singapore, 24 survived internment.

The “Mata Hari’s” fate was to be captured by a cruiser and a destroyer. We were halted in the early hours of Saturday, 14th February and when daylight appeared a boarding party was sent by one of the warships to inspect our craft.

Prior to the boarding our skipper warned that the Japanese troops would search and confiscate all articles of value. My father had two diamond rings left with him by mother to assist us should we not escape. These were secreted between my toes in my tennis shoes and I am pleased to report that they survived to provide vital assistance when disposed of on the black market when things got particularly grim.

An incident, one of many at around that time which will always remain with me, was that during the inspection a Japanese sailor with a bayonet attached to his rifle was checking out the passengers lined up on deck. When he got to me he took a lunge and the tip of the bayonet struck an object inside my shirt which happened to be my drinking utensil. There were tins of 50 cigarettes around in those days and as there was nothing else available I improvised and emptied and cleaned out one of them to drink from. When the lunge came I jumped back and, just as well, otherwise I would be sporting a scar today. My immediate reaction was to fetch the tin out to show that it was not a grenade.

Eventually we were escorted into Muntok Harbour, Bangka, where we caught up with the survivors from “Vyner Brooke”, “Giang Bee” and various other craft.

Within hours our captors separated the women and children from the men who were placed in Muntok gaol.

Our first night in the gaol was a somewhat frightening one. When we had settled in, so to speak, around 7.30pm when it was totally dark, we heard yells and blood curdling screams coming from the gaol entrance. We immediately thought the guards had got stuck into the “sake” (Japanese rice wine) and were on a rampage which would see us cut to pieces.

As it turned out the noise came from a horde of Asian prisoners who had been brought to the gaol to spend their first night there. We were totally segregated from them.

The next morning we got an even bigger shock. At daybreak we prisoners, excluding the Asians, were put into trucks and taken to a large expanse of flat ground where several trenches had been dug. We were lined up in front of these trenches so the first thing that came to mind was a bullet in the back of the head. As it happened we were on an airfield and the Dutch had dug the trenches to prevent its use by the enemy. Our job was to fill in the trenches and we were provided with tools to do it. Oh, what a relief.

Six weeks later we were transported to the mainland in the city of Palembang, Sumatra, and a gaol again became our home for the next ten months.

In May I contracted amoebic dysentery and was extremely ill. Fortunately at that time Charitas Hospital in Palemgang was still operating and I was moved there from the gaol. It was a Catholic hospital staffed by nuns who did a marvellous job. I was the patient of a Dr Goldberg, a woman, and I cannot thank her enough for getting me through the illness. I spent about six weeks in the hospital and when taken back to prison had shed 2 stone 7 lbs (16 kg) from my weight of 7 stone 10 lbs (49 kg). It took a long time to recover fully and coincidentally when the war ended I had got back to my exact original weight BUT in the meantime had grown six inches in height!!!

A camp which we called Barracks Camp, and which we helped to build in the city, became our domain for the following eight months.

In September 1943 our captors decided to return us to Muntok gaol on Bangka where we languished until March 1945. This was a horrific period, which saw an immense acceleration in the death rate.

Finally, with a certain amount of relief, we were transported, via Palembang, by sea, rail and truck to a disused rubber estate in central Sumatra at a place called Belalau. We were accommodated in workers quarters and the area was surrounded by barbed wire. This location afforded the opportunity to break out to raid local smallholdings in order to pilfer produce such as tapioca, papaya (pawpaw), bananas and any other edible crops. Those game enough to take the risk were able to augment their meagre camp diet.

My partner on these missions was a chap by the name of McCann from Western Australia. I would emphasize that the risks were real. Two persons who were caught were removed from camp and were not seen again. Japanese soldiers needed little excuse when it came to exercising their brutality.

There was an occasion when I could have been strung up. On one of our daylight excursions (we would go out at night as well) when McCann and I were returning with our spoils, McCann made it safely into camp. It was always arranged that we would receive a wave from someone inside to indicate that the way was clear. When it was my turn, I got the signal but unfortunately for me the guard who had passed by decided to turn back just as I was stepping through the fence and he saw me. I got in all right but a roll call was immediately brought on to see if the guard could pick me out and he did.

I was marched off to the guardhouse and kept there overnight. Efforts were made periodically by my captors to get me to admit that I was the culprit with assurances that no harm would come to me but I had the good sense to deny being the person. Meantime I was getting beaten up on a fairly regular basis. Eventually when daylight came I was released and I owe this to our British camp leader, Hal Hammett, who worked on the Jap camp commandant for most of the night pleading my case. Incidentally, I was Hal’s bridge partner so he obviously didn’t want to lose me!

I suppose McCann and I made about seven trips beyond the wire and that was stretching our luck. One dangerous aspect in breaking out which we seemed to ignore was the wildlife out there in the jungle.

Sumatra at that time was known for having a significant number of tigers and others of the cat family plus a few bears and snakes but we never gave it a thought. Obviously the desire to survive starvation was more compelling.

One of the tasks I had for a period of eight months was as a member of the burial party at Muntok gaol the second time around. It was particularly harrowing when one had to place in a coffin someone who had become a close friend and this occurred a few times. After a time it became less sad and depressing.

The overall British mortality rate in our men’s camp was 54½ % and, in the women’s camp 30% failed to survive.

Malnutrition was the main contributor but when you add to this the fact that medical supplies were pitifully meagre to cope with diseases such as dysentery, beri beri and malaria, it was perhaps fortunate that many more didn’t die.

Rice was our staple but there was never enough, and meat and vegetables were at starvation levels. Bread, for instance, was non-existent and fruit seldom seen.

Out of the thousands of tons of Red Cross parcels that would have been destined for us, each prisoner received about ½lb butter, ½ tin bully beef and one packet of cigarettes in 3½ years. The Japanese polished off the rest.

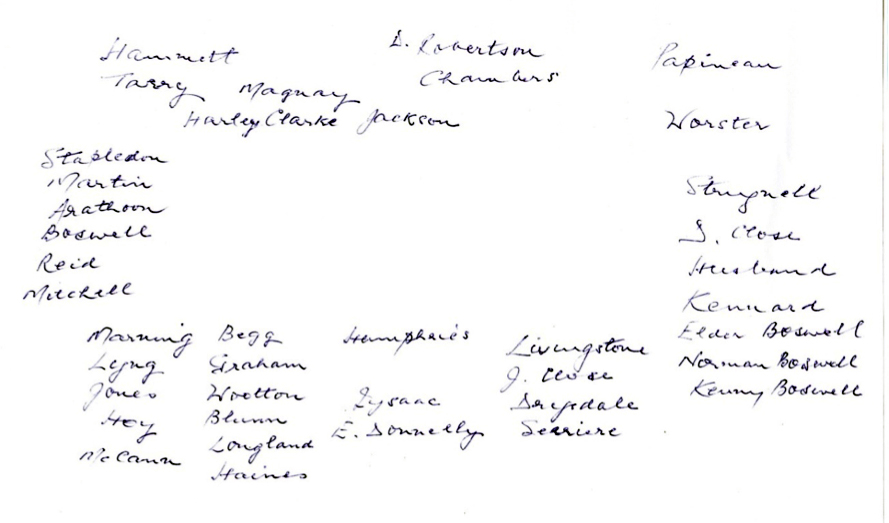

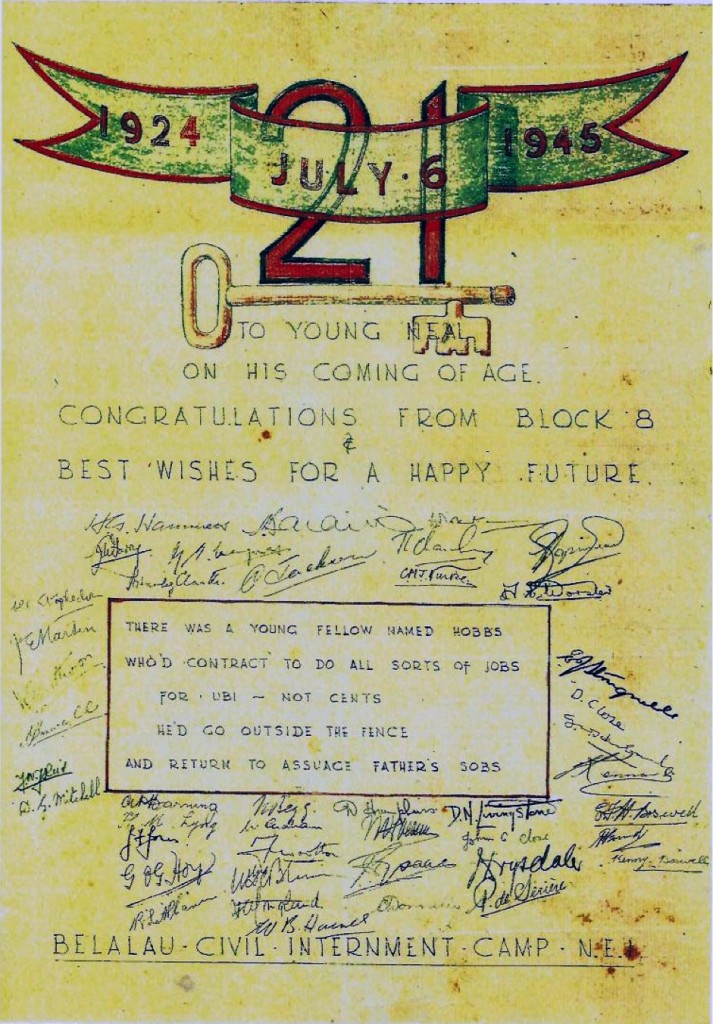

I had my 21st birthday as a prisoner a month before hostilities ceased and received, on probably the last sheet of paper available, a memorable birthday card to celebrate the occasion. The wording reads:

1924 – 6th July – 1945

To young Neal on his coming of age

Congratulations from Block 8

Best wishes for a happy future

(Card was signed by all 43 members in my Block)

A limerick was added which reads as follows:

There was a young fellow named Hobbs

Who’d contract to do all sorts of jobs

For Ubi not cents he’d go outside the fence

And return to assuage father’s sobs.

Ubi, as mentioned above, is the Malay/Indonesian word for potato and in this case specifically refers to the tapioca root.

In early September ’45 we were flown out of Sumatra to Singapore where we boarded a ship to Sydney. A few days later a Dakota took us to Perth to join my mother and sisters.

***********************************

Tales of a prisoner of war by Naveen Mathew Menon. New Straits Times [Kuala Lumpur] 28 June 2008:

KUALA LUMPUR: Octogenarian Neal Hobbs returned to the land of his birth recently to reminisce about the good and not so good old days. He vividly recalled what it was like growing up and working in Malaya, and the suffering under the Japanese in World War 2.

The former prisoner of war said this will probably be his last visit. He had come to the New Straits Times library to look for pictures of himself and his family.

Horse racing aficionados may recognise the name of his father, Robert Neal Hobbs, a successful jockey and race-horse trainer. Both father and son were well-known sports personalities here back in their glory days.

Hobbs now lives in Brisbane, Australia. Before his retirement he was an air-conditioning sales administration manager with Carrier.

Q & A Neal Hobbs

Q: Tell us about your early years in Malaya.

A: I was born in Kuala Lumpur in 1924. I attended primary school at the Batu Road School. In 1938 I went to Victoria Institution (V.I.) and was there till my final year in 1941. During the Christmas holidays that year, theJapanese trooped in.

I did not leave this country from the time I was born till 1941, when I was captured by the Japanese and taken to Bangka Island in Indonesia. I was 21 years old when I was released after 3-and-a-half years as a prisoner of war. I went to Australia and after I recovered my health I came back here in 1946, and lived and worked here for 19 years.

A couple of years before I left in 1965 I became a Malayan citizen. But I had to give it up when I went to live in Australia.

Q: What work did you do here?

A: I was a stock broker for a company called Charles Bradburne, and later on a rubber broker.

Q: What made you visit Malaysia this time?

A: I was talked into it by my daughter. She was born here as well.

Q: Is this your first visit since you left in 1965?

A: No. I came back here in 1972 for a few days to meet up with my wife who had taken my daughter to visit her relatives in England. I was working and couldn’t go with them. It’s been over 30 years since I was last here.

Q: You were a legendary cricketer here…

A: I played cricket at V.I. before the war. After World War 2, I played for the state for about 10 or 12 years. Every year there was one fixture – North versus South. North was Selangor upwards to Perak and Penang, while South was Negri Sembilan, downwards.

I was selected to play for Malaya against Hong Kong, but unfortunately I had just switched jobs and didn’t want to take the risk of going to Hong Kong at that crucial time and asked to be left out.

Q: What about local food, do you like it?

A: I’m crazy about local food … I virtually grew up on it. In the last four or five years before I went back to Australia I used to have nasi lemak for breakfast almost everyday. I love hot kuey teow and mee goreng. My wife and I used to go to the Madras cinema and afterwards to the stall just outside for fresh wet popiah. It was absolutely fabulous.

Q: How and when did you become a POW?

A: When the Japanese came in we were chased down to Singapore like a lot of other people. On the 12th of February 1942, three days before Singapore fell, we scrambled out of the country, like hundreds of other people did, on any available vessel.We took off to Perth, but unfortunately we didn’t get far because the Japanesecaptured us at sea and took us to Bangka island near Sumatra. We spent 3-and-a-half years there being moved around from one prison to another. Luckily my mum had left for Perth a month earlier with my sisters.

There were three ships in our particular convoy. When we were sailing out of Singapore our ship got lost in a mine field. The other two vessels, one with Australian nurses, were sunk by Japanese planes. Some people swam to shore while others drowned. On one of the beaches of Bangka, the Japanese shot about 21 nurses. One survived, and she went to the war crimes trials after the war to give evidence.

Q: Do you remember your days in prison?

A: We were in a civilian camp. The main problem for us was slow starvation. We got rice and tapioca – very little of it. We weren’t fighters or soldiers. We just got in the way, so the sooner we died the better as far as they were concerned. So instead of putting us against the wall and shooting us, they decided to starve us to death. We were so run down many picked up malaria, dysentery, cholera and other diseases. About 55 per cent of the prisoners in our camp died. But I was lucky. My father and I were together and we both survived.

The women’s and men’s camps were separated and we were never allowed to see each other. Even husbands and wives were never allowed to see each other, and didn’t even know whether either one or the other had died. In jail we had a couple of feet of space, and they didn’t provide us with any beds or mattresses. We slept on concrete, and gunny sacks softened the hard surface.

Q: How did you survive?

A: In the final camp, some of us supplemented our diets. My father was so frail at that stage I thought I should do something to get some extra food. Our camp in a disused rubber estate was surrounded by barbed wire, but a few of us plucked up enough courage to go out at night and eventually during the day too. We used to raid the ladang for tapioca and other things. If you were caught, you were executed. That was the risk we had to take.

Q: Did your mum and sisters know you were alive?

A: No, in those 3-and-a-half years, they didn’t get any information about us, whether we were alive or dead. TheJapanese gave us post cards to write a couple of times which they said they would send through the Red Cross, but I guess they all ended up in the dustbin. My mum and sisters only realised we were alive when we got to Singapore after our release.

Q: What do you think of Malaysia now?

A: I hardly recognise many of the places because of all the changes. New streets, new buildings …things have changed. Even the names of the old streets are different, and that confused me a bit. In Singapore nearly all the names of streets are still the same. The present Federal Hotel was the Federal Hotel back then, but obviously it’s not the same building. And the Pavilion cinema is a car park today. But the people are extremely polite and helpful. That hasn’t changed.

Q: Where did you meet your wife?

A: I met her in Penang. We were married here in Kuala Lumpur.

Q: What did you do for relaxation?

A: After the war, when we came back here, we used to go to the cinema quite a lot, the Odeon near Batu Road, the Madras cinema and the Pavilion.

Q: Where did you go for your holidays?

A: Fraser’s Hill! I used to go up there and play golf. Also Cameron Highlands and Port Dickson.

Q: What is your most striking memory of Malaysia when you were working here?

A: I just loved the atmosphere of the place, the relaxed attitude of everyone – the locals and the foreigners. I played a lot of sports and I mixed with a lot of local people and I got on extremely well with them.

Q: What kind of sports did you play other than cricket?

A: I was a very good golfer and was a member of the Royal Selangor Golf Club for a number of years. For two years, I was also the captain of the Selangor Club hockey team.

Copyright New Straits Times Press, Ltd. Jun 28, 2008

In 2016 this website was contacted by the grandson of George Bryant, one of the civilian internees. Neal Hobbs was asked if he remembered George and in an email reply he wrote: