This page owes much of its content to the research work carried out by Michael Pether. We are very grateful to all the many years that Michael has devoted to uncovering who was on board each of the ships and a page that lists all the research undertaken by Michael can be found here.

The escapes to Sumatra and Java (and Ceylon) during this period involved every type of craft that floated – two man canoes or ‘praus’, sampans, tongkangs, 12 foot skiffs from the Singapore Yacht Club and Changi Garrison Yacht Club, private launches, junks, pleasure yachts (‘keelboats’ – called ‘keelers’ in New Zealand), tug boats of every description, small coastal vessels which had been converted into auxiliary patrol boats, Royal Navy ‘Fairmile’ fast patrol boats ( HMMLs and HDMLs) of about 100 – 123 feet, many small merchant ships converted into auxiliary minesweepers, specialty vessels like the RAFA (RAF Auxiliary) ‘Aquarius’, ex-Yangtze river gunboats like ‘HMS Scorpion’, ‘HMS Grasshopper’ and ‘HMS Dragonfly, ex- Yangtze river passenger vessels like ‘HMS Li Wo’ and river tugs like ‘HMS Yin Ping’, then many merchant ships up to the size of the ‘SS Gorgon’, ‘SS Plancius’ and ‘SS Empire Star’ (even another named ‘Aquarius’ of 6000 tons which has created great confusion with the RAFA ‘Aquarius’) – a few of which went directly to Colombo which is something not really known – through to RN and RAN destroyers and light cruisers like ‘Tenedos’, ‘Hobart’, and ‘Danae’.

This page describes some of the ships that carried those fleeing from Singapore, most of whom ended up in the camps at Palembang and Muntok. It is said that 44 ships carrying evacuees left Singapore between February 12 to 14, 1942 and that of these vessels, all but 4 were bombed and sunk as they passed down the Bangka Straits from Singapore to Java. Thus thousands of men, women, and children were killed before any could reach land. A two page list of all the ships that left Singapore between 13/2 and 15/2 and what happened to each one can be read here.

The reason for this tragic loss of life was as a result of a large Japanese naval force which was anchored at the head of the Banka Straits directly in front of the ships carrying evacuees.

General Percival would write “I regret to have to report that the flotilla of small ships and other light craft which left Singapore on the night of 13-14 February encountered a Japanese naval force in the approaches to the Banka Straits. It was attacked by light naval craft and by aircraft. Many ships and other craft were sunk or disabled and there was considerable loss of life. Others were wounded or were forced ashore and were subsequently captured.”

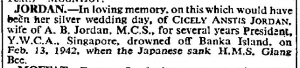

Some of the survivors of the bombed ships were later picked up by one or other of the four ships that made it through. These survivors were from such ships as the Giang Bee, the Kuala, The Redang, ….. The four surviving ships were:

1. The Mata Hari

The “Mata Hari” sailed from Singapore for Batavia on 12 February 1942 with a ship’s complement of 483: 9 officers, 72 European ratings, 2 Asian crew, 30 Royal Marines and 60 Royal Naval personnel from the Prince of Wales and Repulse, 60 Army personnel, 118 civilian men and 132 women and children. Three other ships in company were all lost. The Mata Hari, like the others, was bombed and strafed by over 80 Japanese war planes but was able to keep going and sustained few casualties. She was captured by Japanese forces 24 km (15 miles) off Muntok on 15 February at 03:00hrs. Her passengers and crew were landed the following day.

The Mata Hari, British, 1020 gross tons, was a P&O ship on full charter to the Admiralty. Many of her officers were British India Steam Navigation Company personnel as follows: Temp. Lieut A.C. Carston, RNR – Commander, Temp. Sub Lieut. A.H. Hogge, RNR – Chief Officer, Temp. Lieut. (E) F.J. Lumley, RNR – Chief Engineer, Temp. Sub Lieut. (E) H.M. MacGregor, RNR – Second Engineer, Temp. Sub Lieut. (E) T.R. Gordon, RNR – Third Engineer, Temp. Actg. Sub Lieut. (E) W. McCrorie, RNR – Fourth Engineer. 2. After she was captured she was taken to Singapore. Prize proceedings withdrawn and vessel released by Sasebo Prize Court 27 December 1943. Renamed Nitirin Maru. Sunk by aircraft 2 March 1945.

Captain Carston filed a report on what happened to the Mata Hari, its crew, and passengers which can be read HERE. Philip Hogge’s description of his father’s escape from Singapore based on his father’s letters and notes with particular reference to the Mata Hari can be read HERE.

2. The Mary Rose

The Mary Rose, a forty-foot motor launch, would fittingly be probably the last ship out of the colony. According to Richard Gough’s ‘The Escape from Singapore’ the launch was skippered by an elderly RN officer (George Mulock) who was ordered to take it through the Banka Straits to Palembang. The launch carried some 38 passengers including: Mr Vivian Gordon Bowden (Australian Trade Commissioner to Singapore), Mr A. N. Wootton (Commercial Secretary), Mr J. P. Quinn (Political Secretary), Lt. Colonel John Dalley of Dalforce and five of his officers, Lt. Colonel H. L. Hill OBE (4/19th Hyderabad, Indian Army), Major K. S. Morgan (Head of Singapore Special Branch), Captain Charles Corry (Malayan Civil Service), Chief Superintendent M. L. Wynne (Assistant Chief of Police, Singapore) Head of Special Branch.

On the evening of 16 February 1942 Mary Rose was illuminated by searchlights from two Japanese patrol vessels in the Muntok Strait beyond the Moesi River, who threatened to open fire on the launch. Captain Mulock refused to surrender, but a close warning shot across the bows forced him to reconsider. In the absence of a white flag, a pair of underpants was found amongst a passenger’s luggage and hoisted. An English-speaking Japanese officer came aboard and Captain Mulock offered his sword to the officer, thus became the last Royal Navy captain to surrender his sword to the enemy.

The Mary Rose was escorted to Muntok harbour on Bangka Island where her occupants were taken ashore as prisoners of war.

3. HMS Tapah

The Tapah was an old British minesweeper and we are fortunate to have five pages of the Captain’s log which gives some details of the ships activities and this can be read HERE

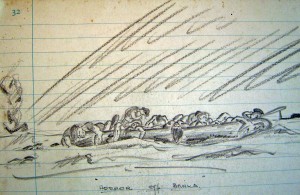

A group of about 42 who had been on board the Giang Bee (see below) had taken to a lifeboat before the Giang Bee had been shelled and sunk and managed to reach the eastern coast of Sumatra. There they were found by the Tapah and about half the party decided to go aboard the Tapah. Unfortunately the Tapah was spotted by a Japanese naval vessel and escorted into Muntok harbor. One description of what happened to those on the lifeboat after they reached land is from Gordon Reis’s diary.

The Giang Bee survivors found themselves on a stretch of land where: …. some three Malays came to us and gave us a few prawns and showed us where we could get water about one mile away … We had the drinking water brought to us and did some cooking mixing the biscuits with condensed milk and water – it was impossible to swallow the biscuits they were so dry and hard. The milk was found in the lifeboat. That evening we built a fire and took watch all night as there were ample evidence of wild pig and the natives said tiger and elephants were near. However, nothing worried us and [Maurice] Phillips and I did a two hour watch. We slept the night on the beach above high water mark. It was quite pleasant and certainly softer than beds I had later.

In the morning (Monday 16th Feb. 1942) we wandered about the shore which had a dismal outlook on to mangrove all around as we seemed to be at the mouth of a river, having left the open sea to go to this place. We were looking especially for water as the source of supply was a good distance away and whenever we saw any small water hole we drank the water – no matter the colour. Some of these were obviously water holes of animals as footmarks were around. We also bathed in the dirty seawater during which time I had to keep my hand above water level … We passed the day on iron rations, did two hour watch at night and woke up on Tuesday, 17th February still on this bit of shore.

Whilst bathing about 10 a.m. a ship came up the “river” from the sea. She turned out to be the Tapah, a small British Auxiliary minesweeper hiding away from Jap air attacks. As soon as they saw us, they sent a boat ashore with provisions, water, etc. She was under Hancock, one of the finest young men I have met and certainly one of the best since war started. In the early morning about 11 of the party thought they would have a chance of making Palembang so they left in the lifeboat that morning. Their later story was they found out the Japs were in occupation so returned to the camp. Hancock sent word to us whoever wished could come on the Tapah and risk it with him. I decided with Phillips to take the risk especially as my hand required medical attention.

We therefore – about 11 of us – left the party in charge of Morton, Miss [Eileen] Higgs and Miss [Leila Winifred] Bridgeman [Bridgman] of the Australian Y.W.C.A. and went aboard the Tapah which was lying about one mile away (written 15.5.42). The party remaining behind was about 22 and I heard they eventually, on the return of the lifeboat, tried to make Batavia, Java. What has transpired I do not know at time of writing but they must have been say 300 miles north of Batavia. The two Y.W.C.A women remained behind really to control the men. [To learn more about Miss Higgs and what happened to the party left behind click HERE]

We got on the Tapah as mentioned and shortly afterwards moved off bound for Batavia. There were crowds on the ship —a small one of say 1200 tons — mostly survivors from some distress or other, and I got a corner on the deck for sleeping room. I had no mattress nor other equipment – having lost all. We carried on in the dark and whilst dozing about 10 p.m. we were stopped by searchlight and signals and eventually Japs came aboard when we then realised we were prisoners of war. This was near the Straits of Banka and not far off Muntok to which part they led us. It was apparent we were in for the duration. In the morning (Wednesday, 18th February) we anchored off Muntok and stayed there all day long. By the way, it was amusing when the officer went to Hancock’s cabin and took over the ship. Their conversation was worth listening to but I cannot detail here for paper shortage. I hope to report it later when we meet.

18.3.42 Towards evening a British captured M/L came alongside and we were ordered aboard … We arrived at Muntok jetty where it started to rain …

See also Ann Silverman’s description below. After Muntok the fate of the Tapah is not known.

The Ships that Sank or were beached

As noted, over forty ships were bombed and sank killing all the men, women, and children on board who either died as a direct result of the bombings or were machine gunned by the Japanese pilots or who subsequently drowned. However, some of the ships had enough surviving passengers who were picked to form an identifiable group. Michael Pether has recently compiled a description of what happened to some of the smaller ships such as : HMS Fuh Wo ; Yin Ping; RAF Auxiliary ‘Aquarius’ ; SS Hong Tat, and these can be read on the Michael Pether Ships Research Page HERE.

Among the ships that sunk were:

The Vyner Brooke

Built in 1928, the SS Vyner Brooke was a British-registered cargo vessel of 1,670 tons. She was named after the Third Rajah of Sarawak – Sir Charles Vyner Brooke. Up until the outbreak of war with the Japanese, Vyner Brooke plied the waters between Singapore and Kuching, under the flag of the Sarawak Steamship Company. She was then requisitioned by Britain’s Royal Navy as an armed trader.

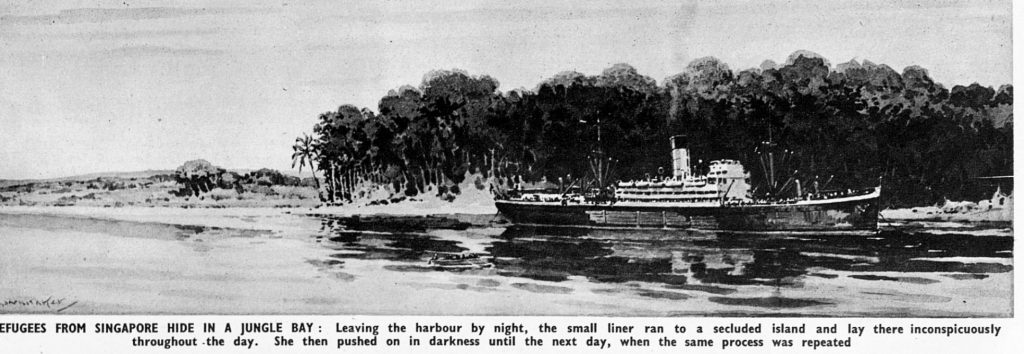

On the evening of 12 February 1942, Vyner Brooke was one the last ships carrying evacuees to leave Singapore. Although she usually only carried 12 passengers, in addition to her 47 crew, Vyner Brooke sailed south with 181 passengers embarked, most of them women and children. Among the passengers were the last 65 Australian nurses in Singapore. Throughout the daylight hours of 13 February Vyner Brooke laid up in the lee of a small jungle-covered island, but she was attacked late in the afternoon by a Japanese aircraft, fortunately with no serious casualties. At sunset she made a run for the Banka Strait, heading for Palembang in Sumatra. Prowling Japanese warships, however, impeded her progress and daylight the next day found her dangerously exposed on a flat sea just inside the strait.

Not long after 2 pm Vyner Brooke was attacked by several Japanese aircraft. Despite evasive action, she was crippled by several bombs and within half an hour rolled over and sunk bow first.

Passengers from the bombed and sinking ship entered the few undamaged lifeboats, jumped into the water or slid down painful rough ropes into the sea, stripping the skin completely from their hands. Some reached rafts or held onto wreckage, while others swam in their lifejackets for long hours which became days and nights, surrounded always by the wreckage from boats, the dead and the dying.

Through the darkness of the tropical night, they could see the blinking light from Bangka Island’s Muntok lighthouse, sometimes near and sometimes further away as the tides pulled them in and out from the shore. One group of Australian nurses, seated on a raft, had been close to land but were pulled back by the tide and swept out to sea. They were never seen again.

Finally, burnt by the sun, dehydrated and exhausted, some people reached land. They sat and lay in groups scattered along the sands of North-Western Bangka Island. Weakened, they tried to look for fresh water or split open coconuts to sip the cooling milk through their swollen, blistered lips.

Approximately 150 survivors eventually made it ashore at Banka Island, after periods of between eight and 65 hours in the water. The island had already been occupied by the Japanese and most of the survivors were taken captive.

However, an awful fate awaited many of those that landed on Radji beach.

The Giang Bee

The following is based on Michael Pether’s description of what happened which can be found HERE. This description also consists of a list of all the passengers who were on board the Giang Bee and who either survived or who died.

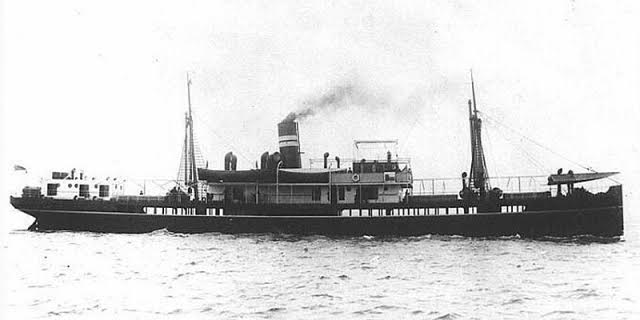

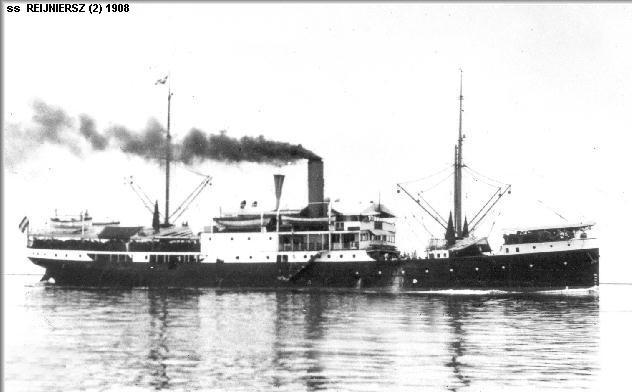

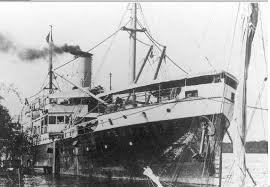

The “Giang Bee” had been built in Rotterdam in 1908 and was originally named the “Reijnierz”. In 1939 she had been sold to the Heap Eng Moh SS Co and renamed “Giang Bee”. Having been a cargo ship there were no passenger cabins, little deck space, but plenty of room in the holds. She had four lifeboats – each could carry 32 people. In April 1941 she was requisitioned into naval service hence the HMS. She carried a four inch gun and depth charges.

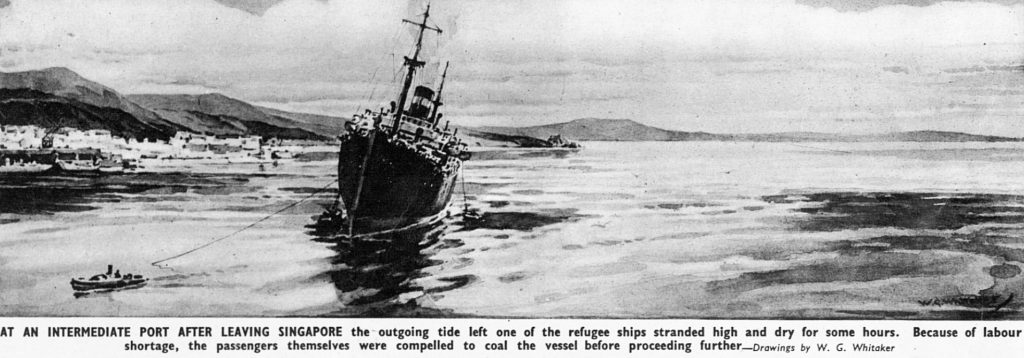

The Giang Bee left Singapore Harbour at either 9 p.m. (ASD) or 10 p.m. on Thursday 12th February 1942. Although Captain Lancaster, in command of the ship, initially refused to take civilian passengers because he saw the dangers attached to a ship designated as a warship, she was loaded with up to 300 refugees (one survivor, Gordon Reis believed there to be 350 people on board) who were mostly women, children, and the elderly.

All her Malay crew had been ordered ashore in Singapore before she left, so that the crew consisted of a few Chinese crew members, a handful of RNVR personnel and some passengers who volunteered to be stokers, etc. One of these was Colin Douglas Campbell. The artist Vladimir Tretchikoff, later known for painting the green-faced Chinese woman, was on board the Giang Bee and in his autobiography, ‘Pigeon’s Luck’, Tretchikoff described entering the engine room as a ‘descent into hell’. Amidst the flames, the heat and noise, the sweaty, labouring bodies shovelled coal as fast as humanly possible, striving for their one chance to escape the Japanese. Tretchikoff wrote:

The heat was insufferable. Sweat poured off us, trickling down our chests and making furrows through the black dust that caked us. Several of the volunteers could not take the heat and had to give up. Some even fainted. Others were pressed into service in their place. We had to keep the boilers at top pressure, to ensure maximum speed. It was our only chance of escape. I found the going hard but managed to survive.

The Giang Bee was bombed and suffered damage during the day of 13th February, and in the evening, after a long stand-off with a Japanese destroyer, she was shelled and sunk in the Banka Strait. There had never been enough lifeboats for all those on board, and two of the four lifeboats had been seriously damaged by the day’s bombing. Due to this and the speed with which the ship sank, a large number of lives were lost.

Whilst there appears to have initially been an attempt by the Japanese to handle the surrender of the ship in a somewhat civilised manner, in the final event the Japanese warships showed no humanity or decency when they were in full knowledge that the ship contained civilians and a huge number of women and children. In a wartime situation at sea it may be understandable they did not stop and pick up survivors, but to leave without even jettisoning flotation devices for the women and children shows a complete lack of human values.

Amongst those on the Ginag Bee were several large extended family groups, most notably the Boswells, Schoolings, Dumbletons, Collins, Sinclairs, van Burens and van Geysels; senior women from the Malaya YWCA and the Singapore YWCA; people who knew each other through the Singapore Recreation Club; a group of professional jockeys and trainers from the Singapore Turf Club and Malayan racecourses, ten employees of the Ministry of Information and the remaining ‘skeleton’ staff of the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation and a number of newspaper men. Staff from William Jacks & Co. (Malaya) Ltd. and several partners from the Penang law firm Lean & Co. Many planters and miners were aboard. Joan Sinclair who was 17 years at the time recalled what happened to her in an article that can be read here.

There were repeated air attacks during the day of the 13th February 1942 – one passenger (ASD) records “…the Japanese planes came over in waves. We were fortunate the first time they unloaded their bombs but when the came back again after 1 p.m. they made a direct hit and caused damage to the engine room. There were several fatalities. I did not even realise that I had been hit in the back by shrapnel in six places. These incidentally were removed a few weeks later…” (ASD) . At about 6 p.m. on that day and when about 170 miles south of Singapore Japanese warships suddenly appeared over the horizon and fired a warning shot across the bows (ASD) ; Captain Lancaster (most sensibly in the eyes of this researcher) ordered the White Ensign to be lowered and also that all women and children should show themselves on deck. He also ordered the crew to throw their weapons into the sea (WFTD p 42)

Two Japanese destroyers approached the GB at high speed, one of them signalling in incomprehensible Morse code, and stopped within half a mile of the GB when one of them sent a launch towards the GB. It was within a hundred and fifty yards of the GB when an RAF or Dutch bomber (Anna Silberman and Gordon Reis in their diaries state there were two bombers) from Sumatra suddenly appeared and began circling overhead; the Japanese destroyers opened fire, the bomber (s) flew off, and the Japanese recalled their launch.

Then followed a long uneasy wait that continued as (is the case in the Tropics) dusk quickly turned into the pitch black of night, when the destroyers then trained their searchlights on the GB. Note: sunset in that area is about 7.20pm at which time it would have been dark.

At about 7.30pm Captain Lancaster (it appears after an instruction signalled by the Japanese for the ship to be abandoned) ordered all women and children to take to the lifeboats – 50 or so in each boat – and a strong tidal current soon swept the lifeboats astern of the GB. It was during this part of the events that earlier air raid damage was revealed – damaged lowering ropes on one lifeboat parted as it was being lowered into the sea and it spilled its passengers into the darkness of the ocean; the second lifeboat was lowered into the sea but it had been holed by bomb splinters and soon began taking water and sank.

This was where it appears that at least half of the women, children and men missing from the “Giang Bee” lost their lives and two survivors recorded in anguish the moment as one of horror – firstly Mr. M. J. V. Miller in his diary (IWM 88/62/1) recalled “…I shall never forget that as long as I live, and the sound of little children calling out for their mothers will be forever in my ears, it was simply heartrending…” and also in the diary of Gordon Reis “…when I got into our lifeboat the screams for help were appalling – mostly women’s voices – obviously from the damaged lifeboats and now struggling in the sea…”.

When Michael Pether was doing the research for the description above, it became apparent that the vast majority of the women and children who were lost in this awful attack on the “GB” would have been the first people ordered onto the first two lifeboats and would have drowned that night in the sea. Some other women refused to leave their wounded husbands behind on board the ship and would have lost their lives in the sinking.

Two further life boats successfully launched with about 100 people in them combined.

When the last lifeboat had been cast off there were still about 100 people on board, so the Captain sent the 13 foot harbour dinghy with Robert Scott and three others to try and make contact with the destroyers.

Regrettably the destroyers kept manoeuvring away from the dinghy so this effort failed. One of the destroyers then apparently signalled for the ‘GB’ to be abandoned because they were intending to sink her.

At about this point many of those still on board took to the sea (GBIR).

Then about 21.30 pm one destroyer fired six shells into the GB which caught fire, glowed red from stem to stern and sank within a few minutes. “…Terrified figures could be seen jumping from the target’s deck, soon ablaze from end to end…” (SDGB).

The destroyers then left with several hundred women, children and men struggling and drowning in the sea.

It seems that most the officers and crew died either on board as the ship went down or after taking to the sea in the darkness without a boat or raft. With them went a number of wounded men on the decks or sheltering in the cabins and bunkers.

“…In one lifeboat [that successfully launched] 56 persons reached land at Djaboes, Bangka Island, whilst the second lifeboat with 42 persons reached the coast of Sumatra. Fifteen occupants of the latter boat were brought to Muntok in “HMS Tapah”, seven made their way to Palembang, and five Chinese whose names are not known…” (NIRC).”;

In the book “Waiting for the Durian” it is recorded that there were about seventy people in the second lifeboat including stowaways under the floorboards. They were galley staff from the ship (p. 58) who left the passengers once the lifeboat made landfall (p. 63).

Anna Silberman’s diary records that there were 47 people in the aforementioned second successful lifeboat launch “… 9 women and two children, the rest were men of different nationalities, including 4 Chinese crew members. We had no competent navigator so roamed the seas for 5 days with a meagre ration of a biscuit per person and a little water. We eventually landed on a mangrove swamp, no habitation, nothing but brackish water and a beach infested with sandflies. We did not dare light a fire in case the smoke would be visible by the enemy. On February 20th we saw smoke in the distance and after some frantic waving it turned out to be a British Minesweeper “HMS Tapah”… A boat was sent to pick us up and it was hoped to take us safely to Batavia… Unfortunately about midnight searchlights played on our ship … and until 2 a.m. we were unaware that we were being escorted by the Japanese Navy. Naval guards rushed aboard and we learnt we had been brought to Muntok, the main town of Banka Island… we were herded along a pier to a cinema hall and found it crowded with at least 1,000 male survivors from the various ships that got away too late…” (ASD)

Again insofar as the occupants of the second successful lifeboat launch who did not board the “HMS Tapah”, “…Fifteen survivors tried to reach Java in a ships lifeboat including Hugh Morton, in charge, second engineer “HMS Lipis” , Rae, naval rating ; V. R. Tretchikoff, Warren Publicity Co., Singapore; Miss Hicks (sic) W. YWCA worker; Miss Brickman (sic) YWCA worker… “ (Record compiled by the Netherlands Indies Red Cross).

Rob Scott’s dinghy picked up a few survivors and, after five days at sea, finally reached the coast of Sumatra – he was interned and later sent back to Singapore to be interrogated and tortured. Later to be knighted as Sir Robert Scott and, post war, a Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Defence he wrote an account of this whole ordeal which can be read HERE and his obituary can be read HERE.

Almost all the survivors ended up in either the men’s internment camp or the women’s internment camp at Palembang – one record states 23 men were interned in the men’s camp at Palembang and 47 women and children in the women’s camp. According to the Straits Times of 24.6.45, the death rate for the migratory camp which began in Muntok and moved to Palembang, back to Banka Island and then to Loembok Linggau was astonishingly high: “…55% of the men died and 33% of the women and children.”

From the approximately 300 people on board there were just over 100 survivors of the sinking. The Netherlands-Indies Red Cross in 1943 at the Palembang internment camp compiled a list (with survivors signing as witnesses) of 104 people who were rescued. This list is carefully witnessed and signed by multiple survivors for each entry.

Some 250 people who were on board have been identified leaving at least 50 people to be accounted for – interestingly in this context, because only Gordon Reis (a survivor who later died in Muntok internment camp) has mentioned it in his diary there seem to have been unauthorised Army personnel on board . This may explain some of the unaccounted passengers, because all records seem to have been made by civilians who knew or recognised other residents of Malaya and Singapore. Army personnel would have been unknown to the civilian groups and may have been shunned by them as well. Specifically, Gordon Reis states in his diary “… I think we had a large number of deserters aboard from the Army in particular …”

Ann Silberman recalled her experience of the sinking of the Giang Bee which can be read HERE (<– PDF)

Perthshire Advertiser, 30th January 1946

“REPORTED MISSING ALMOST FOUR YEARS AGO, SUB. LIEUTENANT ROBERT H. CAMPBELL OF THE MALAY NAVAL RESERVE HAS NOW BEEN OFFICIALLY PRESUMED KILLED IN ACTION.”

“The ‘H.M.S. Giang Bee’, a Chinese-owned coastal steamer requisitioned and used as a patrol vessel, left Singapore Harbour – according to a statement made by a number of those who were on board – at 10 p.m. on Thursday 12th February 1942.”

“Although Captain Lancaster, in command of the ship, initially refused to take civilian passengers because he saw the dangers attached to a ship designated as a warship, she was loaded with up to 300 refugees (one survivor, Gordon Reis believed there to be 350 people on board) who were mostly women, children and the elderly.”

“All her Malay crew had been ordered ashore in Singapore before she left, so that the crew consisted of a handful of R.N.V.R. personnel and some passengers who volunteered to be stokers etc.”

“She was bombed and suffered damage during the day of 13th February, and in the evening, after a long stand-off with a Japanese destroyer, she was shelled and sunk in the Banka Strait. There had never been enough lifeboats for those on board, and two of them had been seriously damaged by the day’s bombing. Due to this and the speed with which the ship sank, a large number of lives were lost.”

“Whilst there appears to have initially been an attempt by the Japanese to handle the surrender of the ship in a somewhat civilised manner, in the final event the Japanese warships showed no humanity or decency when they were in full knowledge that the ship contained civilians and a huge number of women and children.”

“In a wartime situation at sea it may be understandable they did not stop and pick up survivors, but to leave without even jettisoning flotation devices for the women and children shows a complete lack of human values.”

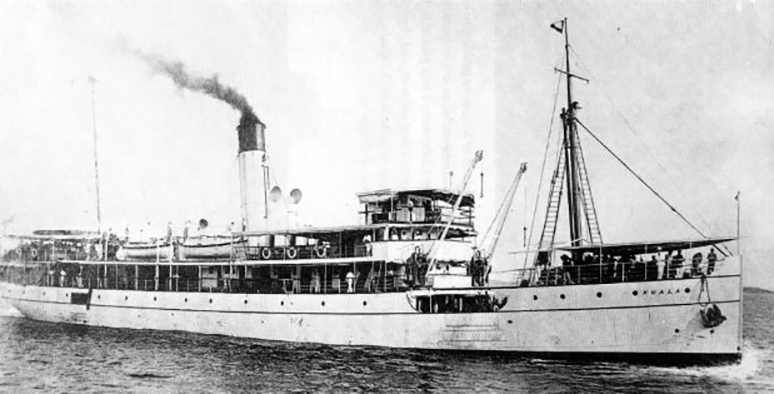

The Kuala: One ship that got quite far away from Singapore but was sunk nonetheless was the Kuala.

The paragraph below that describes the sinking is from ‘Singapore to Freedom’ by Oswald W. Gilmour, (1950), who was on board the Kuala:

“As St Valentine’s Day 1942 was nearing its close, a state of affairs which defies description prevailed in this section of the Malay Archipelago. Perhaps never before in the long period of recorded history was there anything to compare with it. Men, women and children in ones and twos, in dozens, in scores and in hundreds were cast upon these tropical islands within and area of say, 400 square miles. Men and women of many races, of all professions, engineers, doctors, lawyers, businessmen, sisters, nurses, housewives, sailors, soldiers and airmen, all shipwrecked. Between the islands on the phosphorescent sea floated boats and rafts laden with people; and here and there, upheld by his lifebelt, the lone swimmer was striving to make land. All around the rafts and swimmers were dismembered limbs, dead fish and wreckage, drifting with the currents; below, in all probability were sharks and above, at intervals, the winged machines of death. Among those who had escaped death from bombs or the sea there was not one who did not suffer from mutilations, wounds, sickness, hunger, cold, dirt, fear or loss and none knew what the morrow would bring forth. It was a ghastly tragedy, a catastrophe beyond measure.”

SS Redang. For more on the Redang please read this PDF file HERE.

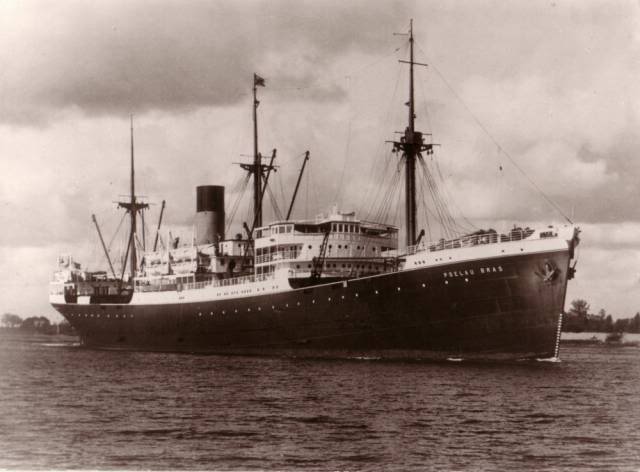

Poelau Bras

Unlike the ships described above, the Poelau Bras set out on February 27, 1942 from the port of Cilacap on the western coast of Java. On March 4 they reached Wijnkoops Bay also on Java. On March 6 one hundred men of the Royal Dutch Navy joined the ship. Already on board were 28 senior executives of the oil company BPM and Shell and passengers rescued from other ships that had been bombed and sunk earlier by the Japanese. The Poelau Bras only had accommodation for 56 passengers and the chaos on board was therefore great as the total number reached some 500 men, women and children most of whom were Dutch. The ship was armed port and starboard, a Bofors-machine gun in a turret was on the stern, and a 10.2 cm cannon.

On March 6, 1942 at 8.00 PM the Poelau Bras left Wijnkoops Bay bound for Colombo (Sri Lanka). The navy men were placed at various locations on the ship creating a further 16 machine guns posts. The engine was ordered to deliver maximum speed in order to get out of the danger zone as quickly as possible. It was assumed that by noon the Poelau Bras would be in range of any nearby Japanese planes.

Poelau Bras Attacked

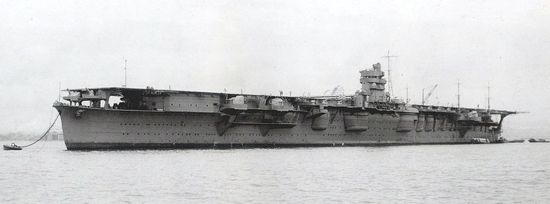

At around 10.30 am there came over the horizon a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft. Then, at 11.40 am a dozen dive-bombers appeared and began to attack. They were Japanese Aichi D3A that had taken off from the Japanese aircraft carrier “Hiryu”.

A total of 12 aircraft were divided into three formations for the attack. Escape was impossible. A bomb hit a lifeboat on the starboard side and another exploded at the height of the engine blowing a hole in the side of the ship. Water flooded the engine room resulting in the engine stalling. Then, a direct hit went straight into the ship’s funnel and a fire broke out in the engine room.

The captain gave orders to abandon ship. Because of the continuing machine gun fire from the bombers many on board did do not dare to get into the lifeboats, but rather jumped overboard in panic. When the pilots of the Japanese bombers noticed that the ship was about to go under, they began shooting at the lifeboats that were now filled with the passenger.

Eventually four of the seven lifeboats were destroyed as well as two rafts. When the three remaining lifeboats were only a few hundred yards away from the Poelau Bras, the bow rose straight up and quickly sank on its stern down into the depths of the sea. When the Japanese saw that the ship had sunk, they returned to their aircraft carrier Hiryu. The Poelau Bras was sunk in position 10 ° 00 ‘ south latitude and 105 ° 00’ east longitude in the Indian Ocean, near Java.

The number of victims of the bombing and strafing was estimated be about 240 to 300 passengers. In the three lifeboats were 116 survivors. After eight days of hardship, lightly dressed in the burning sun, meager water rations, and little food, they reached a small island.

However their freedom did not last long and at Semangkabaal on Sumatra, they were captured by the Japanese. From there they were transported by train to Palembang . (See Song of Survival for more details of the sinking of the Poelau Bras) .

THE LI WO

Last run South

James Ritchie Grant. Sea Classics Aug 1998

By any account the lone British river gunboat LI WO was no match for a Japanese warship. Instead of fleeing south out of the debacle of Singapore the gunboat’s defiant skipper turned his bow toward a Japanese troopship and ordered their guns to open fire as he prepared to ram the enemy.

Pressed into naval use, the 707-ton flat-bottomed patrol boat HMS LI WO was armed with a makeshift 4-inch gun and a single depth charge launcher. Surviving the retreat from Hong Kong the bantam gunboat’s luck ran out when she single handedly took on warships during the evacuation of Singapore.

In the fortnight leading up to the surrender of Singapore some 13,000 civilians and service personnel were either evacuated or left the island in an official capacity.

As the Japanese forced their way across the island, large numbers of poorly-equipped pleasure craft also fled Singapore for Sumatra, however a high proportion failed to survive the crossing.

HMS LI WO was a 707-ton flat bottomed patrol boat formerly operated on the Yangstse River by the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company. The ship had been built in Hong Kong in 1938 and incorporated bulletproof armor around its bridge as a result of regular sniper fire on ships plying their trade on the river. No one ever described the LI WO as beautiful and the superstructure consisted of three levels of cabins which ran from the stern to just short of the bow. On this space the Royal Navy mounted an obsolete, Japanese-manufactured, 4-inch gun when the ship was requisitioned in December 1941. Two machine guns and a depth charge launcher completed its offensive capabilities.

LI WO had eluded the Japanese once before, having been ordered to sail from Hong Kong just before the Japanese Army overran that colony, and had reached what subsequently proved to be the illusory protection of Fortress Singapore. A hostilities only vessel, of dubious offensive value, LI WO as to be used in an action which would have gladdened Nelson’s heart.

The ship was commanded by Lieutenant (Temp) Thomas Wilkinson, a professional seaman for almost 30 years. He had served with the Blue Funnel line during the Great War and before coming to China in 1922. Wilkinson was described as a well-liked man, keen on physical fitness, who neither smoked nor drank. More importantly Wilkinson had the ability to make men follow him and understood fully what was required of himself in any given set of circumstances. He also indulged in the pastime of sunbathing, at a time when such ideas were regarded as akin to madness.

From the time of its arrival in Singapore right up the day of its departure LI WO carried out coastal patrolling and the rescuing of crews from bombed ships.

At 0220 on Friday the 13th February 1942 LI WO, in company with a number of vessels, sailed from Singapore Harbor for Batavia with a total of 84 men on board. Apart from the regular crew there were survivors from a number of warships as well as army and air force personnel, all but ten of whom would not survive the voyage.

By the afternoon of the 14th the ship, now separated from the other ships with which it had sailed, had survived four attacks by Japanese aircraft. The highly maneuverable vessel had been handled in a spirited fashion by Wilkinson and came out of each attack with only minor damage, however their limited supply of ammunition was already running low. Just after 1600 hours, as they approached Bangka Island, time ran out for the LI WO and its crew. On the horizon appeared part of the Japanese invasion fleet heading for Sumatra. Wilkinson called his men together and told them that he had decided to attack. With their full support he turned his gunboat toward an enemy fleet of at least fifteen ships.

Whether the Japanese assumed the ship was one of theirs or, justifiably, failed to recognize the hostile intent of the small vessel they did not take any defensive measures as the ship closed to 6000 yards.

At 1645 hours two battle ensigns blossomed forth and its 4-inch gun fired the first shot of the engagement at a troopship whose decks were crowded with soldiers. Details of the action are disjointed due to the death of so many of the participants but the main details are clear.

As the LI WO closed with its target it came under fire from various small caliber weapons which failed to prevent it first setting fire to the transport and then ramming it. Still under control LI WO pulled clear of its victim but was repeatedly hit by shells from the escorts which had come into the fight. The official account of the action states that LI WO’s crew fought for an hour before the ship was reduced to a burning hulk by the enraged Japanese.

The order to abandon ship was given, however as all internal communications had been cut; a search was made of the ship to ensure that all those who were still alive were aware of the order. Those who could quickly responded but Wilkinson, who had previously said that if he wasn’t killed in the fight he would go down with his ship, remained on board.

Billowing smoke and flame the ship sank slowly, going down by the bows, as the men swam for their lives. As they hoisted themselves aboard the life rafts they realized that the Japanese had not yet finished with them when one of their ships steamed through the survivors machine gunning the men in the water and on the rafts.

Just how many of the crew managed to get off the ship is not known but at least ten reached land. As the survivors clung to boats, rafts or whatever debris still floated, Japanese aircraft flew over and two destroyers gave them a cursory glance but offered neither violence nor assistance. Gradually men made their own decisions on what to do next. Some stayed with the rafts, others tried to swim to the nearest island.

One group came across a life raft which had three more of the crew on board and joined up with them. Gradually the raft drifted toward Bangka Island and to their delight they saw a launch traveling in their direction. Their initial joy quickly turned to despair as they found that the launch was filled with burned and wounded men and that its crew had already surrendered to the Japanese in order to obtain medical assistance at the hospital at Muntok.

LI WO’s crew, who were not yet ready to surrender, were filled with admiration for the men who were willingly sacrificing their own chance of freedom to care for their compatriots. Returning to their raft the gunboat’s crew paddled to the shore and took shelter in the jungle. They decided to cross to the eastern end of the island where they hoped it would be easier to get a boat to take them to the nearest Allied-held island.

They traveled for several days then one evening two men, returning from seeking coconuts, found that a Chinese gang had killed one of their companions and had seriously wounded most of the others. It was now obvious that if any of the wounded were to survive they would have to surrender, and so they turned back toward Muntok.

The decision to continue on this course of action was not made any easier as they kept coming across the bayoneted bodies of other Allied soldiers and airmen. Slowly the party approached Muntok and on the nineteenth day since they had lost their ship they came across a road and flagged down the first Japanese truck to come along. To their relief they were taken on board and driven to the prisoner of war camp at Muntok.

After three and a half years incarceration the survivors returned to tell the story of LI WO’s defiant action. This resulted in a posthumous Victoria Cross for Wilkinson, and four medals and six mentioned in dispatches to members of the crew.

Lieutenant Thomas Wilkinson RNVR, a professional seaman for 30 years, vowed he would see the gunboat HMS LI WO go down fighting. He made good his promise in a valiant battle off Island that cost him his life.

References

Stand By To Die, A.V. Sellwood.

The War Against Japan, Maj.-Gen. S. Woodburn Kirby.

London Gazette, 3rd Supplement, 17/12/1946.

London Gazette, Supplement, 25/11/1947.

Various books covering the fall and evacuation of Singapore. SC

THE EMPIRE STAR

The Empire Star, 12,656 gross tons, owned by Blue Star Line, Captain S.N. Capon, was one of the last vessels to clear the port of Singapore. Under aerial attack the whole time her departure was marred by much confusion in the port area. Some people missed their allotted ship, others jumped aboard the first they came upon, some tragically lost their places altogether.

Empire Star with cabin accommodation for only sixteen passengers sailed during the early hours of 12 February carrying a total of 2,154, mostly staff from the Military Hospital, Australian and British Nurses. Four hours later Empire Star sustained three direct hits as six dive-bombers came out of the tropical dawn – fourteen were killed and seventeen badly injured. Great damage was inflicted and the ship was set on fire in three places.

Although the attacks continued throughout the morning and many of the bombs were near misses, the Blue Star merchantman miraculously escaped further damage. She arrived at Batavia 40 hours later and after a short stay sailed for Fremantle. The Empire Star was later torpedoed and sunk on the 23 October 1942, at position 48 14′ N. 26 22′ W. by U615, commanded by Kapitän Leutnant Ralph Kapitzky. Four men were killed on board. Captain Capon’s boat with 26 crew, six gunners and six passengers was never seen again.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ASD = Diary/ memoir of Anna Silberman

CWGC = the website database of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

GBL = handwritten list of names headed “Giang Bee” (p.31) at PRO

LOPBGB = List of Persons believed to be on “GB” held at the UK National Archives.

MVDB = database researched and compiled by John Brown of the United Kingdom, comprising the vast majority of men who were in the FMSVF, SSVF, MRNVR, MVAF etc at the time of the invasion of Malaya by the Japanese.

MVG = list of evacuees researched by author and Malayan researcher, Jonathan Moffatt, available on Malayan Volunteers Group website

NIRC = typewritten document prepared by the Netherlands – Indies Red Cross at Palembang in February 1943 where people are noted as having been last seen on the “GB” and each entry signed as witnessed by specific survivors; also records a summary of events as known to survivors at that point. Held at IWM.

SDGB = book “Singapore’s Dunkirk” by Geoffrey Brooke, ISBN 0-85052-051-7, first published 1989 by Leo Cooper.

ST = book “Sinister Twilight” by Noel Barber , published by Readers Union Collins 1968

STA = the on line archives of the “Straits Times” and many other newspapers of Singapore and Malaya available on the website newspapers.nl.sg managed by the Singapore National Library

WBTW = book “Women Beyond the Wire” by Lavinia Warner and John Sandiland

WFTD = the book “Waiting for the Durian” by Susan McCabe, being the story of the Woodford family during these event.